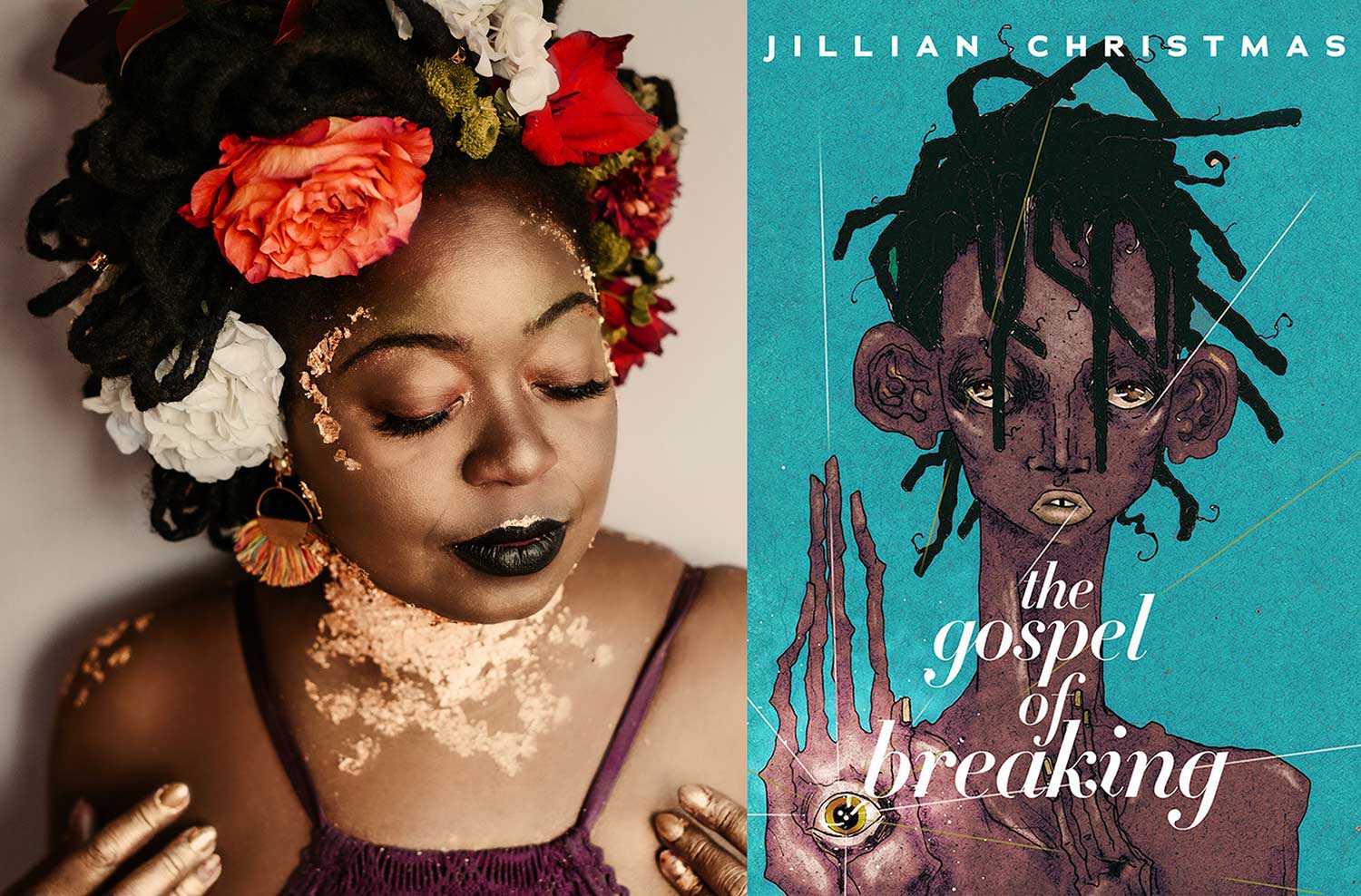

Next up, Chimedum Ohaegbu chats with Jillian Christmas, who is—in addition to being a festival author—one of the programming committee members of Growing Room 2020 and the host and curator of the opening night event at Fox Cabaret. The writer and artist is a force in the spoken word/slam poetry community as a performer, facilitator, anti-oppression advocate, and former Artistic Director of the Vancouver Verses Festival of Words. Read what Jillian has to say about being afraid of the internet, her highly anticipation book of poetry coming out, and page vs performance poetry.

To celebrate the upcoming Growing Room Festival 2020, we are chatting with a few festival authors to learn more about them and their work until March rolls around. You can read all the #GrowingRoom2020 interviews here. Next up, Chimedum Ohaegbu chats with Jillian Christmas, who is—in addition to being a festival author—one of the programming committee members of Growing Room 2020, and the host and curator of the opening night event at Fox Cabaret.

Jillian Christmas is a force in the spoken word/slam poetry community as a performer, facilitator, anti-oppression advocate, and former Artistic Director of the Vancouver Verses Festival of Words. She’s appeared on stages and workshops across North America and the internet. The Gospel of Breaking, her highly anticipated first book of poems from Arsenal Pulp Press, extends her signature style to the page. She lives in Vancouver. Read what Jillian has to say about being afraid of the internet, page vs performance poetry, and her highly anticipation book of poetry coming out in March 2020.

This interview was conducted over email. Photo by Kay Ho.

ROOM: “poet searching mourning” left me breathless, and many of the poems in The Gospel of Breaking deal with the body and how the world touches it (gently, cruelly, otherwise). How do you approach evoking a physical, not just emotional, reaction from the reader/audience with your work?

Jillian Christmas: I tend not to make much distinction. I often experience my emotions as physical. Mistrust, elation, concern, all live in my body. I’ve learned this more recently from body workers and somatic therapists who have treated me. My body is a language and instrument all its own. I think for most people there are deep access points to emotional healing in the body and vice versa. I aim to speak into those places.

ROOM: As a performance poet, what’s gained in writing poems for the page? What’s lost? How does capitalization and punctuation choice—for example the (parenthetical) titles—relate to the losses/gains of page vs performance poetry?

JC: I love this question. I thought a lot about how or if I would be able to translate certain elements of my performance into form on the page. In some cases I think that was achieved with spacing, or capitalization, meant to convey movement of one kind or another. In some cases I think it is impossible to capture a facial expression, or a slight rise in intonation. In most cases I learned that a direct translation wasn’t needed. Many of my performance pieces find a new life on the page in ways they could not have grown or stretched on the stage. I am grateful for that.

ROOM: “Black Feminist” deals with the violence whiteness as an institution and white womxn have dealt to feminism and the Black womxn fighting for it, and uses both anger and humour to spearhead the critique. How do you balance these two elements? Are they both fuel, or does deploying them drain you as a writer? If the latter, how do you take care of yourself and/or ask community to do so?

JC: Sometimes I notice that when I feel safe and in the company of people who understand me, I can express anger as humour. The retelling of a ridiculous experience of racism can cause laughter in the company of friends. Perhaps I also call upon it in the environments of these poems, when the company of friends and allies is needed for affirmation and safety.

I’ve also always enjoyed stories and poems that carry their audience through difficult territory using the mechanism of humour, especially when the reader is not given the luxury of knowing where their own laughter might take them. The understanding that comes after the uncomfortable laughter has already begun. I think that is an exceptional place of openness, with such potential for learning.

In balance, I don’t experience either as draining, though sometimes certain people’s reactions to black humor or anger do feel quite draining.

ROOM: “hard to tell if this is just the internet, or another dream where I am in front of the class in only my dirty underwear” talks about social media affecting you or “Jillian,” the poet. Have you found that social media has influenced your poetry? Do you resist its effects, or try to work with them?

JC: This poem could have lived in an entirely different book, entitled I Am Afraid of the Internet. It is about the way shame moves through those spaces which I typically avoid. I try not to let it influence my writing too radically, however I would be wrong to say it doesn’t live there as well. Shame is tricky that way.

ROOM: A struggle between Black joy and the world’s fetishization of Black pain is woven throughout the book, for example in “Do Not Feed.” What gives you joy, and how do you hold onto that through poetry?

JC: There are so many things that bring me joy, and I am often quite protective of them, my relationships, the sweet animals I journey with, other writer friends, collective POC uprising, healing, and resistance, intentional and thoughtful celebration, magic, medicine, ceremony, cooking (with loved ones and alone), gardening. Some of these I can only hold onto by sharing them, because I believe that love multiplies when it is given freely to those who are prepared to hold it. Some of these I hang onto by keeping them sacred for myself. Most of them live in some form of poetry or music but not everything I create is for other people. There is a special kind of joy in keeping some secrets for myself.

ROOM: As a very lapsed Catholic, “Things I can do” made me wonder: how has faith—not necessarily of the religious variety—changed your writing process?

JC: I don’t know if faith has changed my writing process, perhaps my writing and searching and questioning is the thing that has most impacted my desire to put my faith in places that don’t support or understand me, and to instead seek out spaces, people and situations that renew, acknowledge and uplift me.

ROOM: I love how much this book loves love, in many of its complexities, and found “(sugar plum),” “(each of the spirits, each of them come),” and again, “Things I can do” especially striking. What did you love about writing this book? Is writing, for you, an act of love? If so, directed at whom, what, or when?

JC: Writing The Gospel of Breaking felt like an invitation to meditate on the people and experiences I have loved and those that have loved me, however imperfectly, into being. There was a lot of opportunity for growth and compassion in that process. I think I fell in love with that experience.

ROOM: How did The Gospel of Breaking challenge you in terms of craft, and how did you work on those challenges?

JC: Honestly I think the biggest challenge was in staying true to my own instincts. Not allowing my impostor-syndrome or fear of academic criticism stop me from taking risks, or being playful or shedding rules and expectation. Amber Dawn is an incredible editor, and she encouraged me in these spaces. She has always been one of my most thoughtful and consistent champions.

ROOM: The “mommy” character recurs throughout the text, dispensing advice about food and danger, giving snippets of her life story. How did you decide where and how often to place her?

JC: I had a very strong instinct that the book needed to be punctuated with the mommy stories, and so I began placing poems by grouping them around these stories and the lessons or emotions they might evoke.

ROOM: What was the main vision you wanted to keep in mind as you took part in programming the 2020 Growing Room Festival and curating the opening night event: The Movement?

JC: I want The Movement to be an opportunity for the celebration of black artists and activists by other black artists and activists. Uninterrupted by fetishization or tokenization, I wanted to create a container where these supreme vocalists and community-activists could honour each other’s work. To that end, each of the artist sharing the stage will be covering a song by one of the other performers that night. Giving their spin and adding their unique flavours to each homage. Together Missy D, Chelsea D.E. Johnson and Tonye Aganaba and DJ Denise will offer their talents in celebration of each other. It will be a thing to witness.

You can join Jillian Christmas at the following Growing Room Literary & Arts Festival from March 11 to 15:

THE MOVEMENT (Opening Night Party)

Black Magic Women: BIPOC Encounters with The Fantastic (Panel)

Radiant Flesh: Black Femme Writing & The Body (Panel)

BELOVED: Flower Crown Workshop (Registration for Jillian’s workshop is subsidized for all QTBIPOC participants. To claim a spot, please drop us an email at festival@roommagazine.com)