Room’s Geffen Semach had the chance to ask Jónína a few questions about her newly publish book of poetry, An Honest Woman, her writing practice, and what she will be looking for in a poetry contest submission.

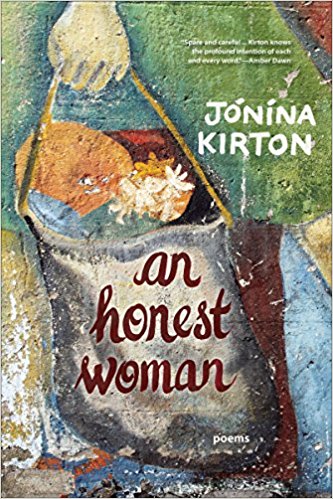

Jónína Kirton, 2017’s Poetry Contest Judge, is a prairie-born Métis/Icelandic poet, author, and facilitator. Kirton graduated from Simon Fraser University’s Writer’s Studio in 2007, and acts as a member of its Advisory Board as well as the liaison for its Indigenous Advisory Board. In 2016, Kirton received Vancouver’s Mayor’s Arts Award for an Emerging Artist in the Literary Arts category. Kirton has also won first prize and two honourable mentions in the Royal City Literary Arts Society’s Write-on Contest in 2013, as well as an honourable mention in 2014 in the Burnaby Writers Contest. Her first collection of poetry, page as bone ~ ink as blood, was released by Talonbooks in 2015. Her second collection of poetry, An Honest Woman, was published in Spring 2017. Kirton is also a member of the Room editorial board.

Room’s Geffen Semach had the chance to ask Jónína a few questions about her newly publish book of poetry, An Honest Woman, her writing practice, and what she will be looking for in a poetry contest submission.

ROOM: Your newest book of poetry, An Honest Woman, explores the lives of women, including your own mother, your contemporaries, as well as well-known sex-crime stories. In wanting to deal with the subject of womanhood, femininity, and the world we live in, how did working with real life people such as Trump, Simone de Beauvoir, or your mother help or hinder you in the creation of a cohesive collection?

JK: Originally, the book was largely autobiographical. I was exploring what it was like to grow up mixed race—Indigenous/Icelandic—with a white Christian mother. I was unpacking the things that I had I learned from my mother about being a woman—about sex, love and marriage—and the ways my Indigenous identity threatened what she wanted for me.

My mother’s ideas of womanhood and femininity were filled with notions of beauty that my almond shaped eyes and brown skin could never achieve. It felt as if all signs of Indigeneity were to be erased. Yet, I had no interest in being feminine or white. Then later, as a teenager and young woman, I could not understand why I could not have sexual agency. Why was a man’s desire acceptable and mine something to fear? This question fueled by my father’s assertion that I was a “slut”; something he started to call me around puberty. The decolonizing of my mind has allowed me to understand that both of my parents said and did many things out of fear. If I could pass and they could get me married off—or as they used to say have someone “make an honest woman out of me”—then they would have done their job.

The book was also intended to examine the ways I had clung to whatever sovereignty I could manage. How could I say all this and still convey that I loved and respected my mother deeply; that losing her to cancer in 1987 shaped my life in unexpected ways. So while the book was an attempt to unpack the complexity of having a white mother and a Métis father it was never intended to bring judgement to either of them. Zeroing in on my parents and our life together brought obvious problems.

And then the U.S. elections brought an unexpected gift. Suddenly the whole world was watching and talking about the very things I was writing about—race, gas lighting, sexual assault and who is considered honest in the “he-said-she-said” arena. Toxic masculinity, the effects of racism and the vulnerability of women was on full display. Given this I was acutely aware that there was an opening and that I could not afford to miss it. In the final hour I restructured the whole book. I added poems about Trump and the Clintons and deleted some of the more autobiographical poems. By doing this I was able to shift the focus to others. This book was no longer about me or my mother or my father. It was about the world we live in. By using real life quotes from someone like Trump, Clinton and Fritzl’s trial I was able to offer indisputable truths about the world that girls are born into.

And then the U.S. elections brought an unexpected gift. Suddenly the whole world was watching and talking about the very things I was writing about—race, gas lighting, sexual assault and who is considered honest in the “he-said-she-said” arena. Toxic masculinity, the effects of racism and the vulnerability of women was on full display. Given this I was acutely aware that there was an opening and that I could not afford to miss it. In the final hour I restructured the whole book. I added poems about Trump and the Clintons and deleted some of the more autobiographical poems. By doing this I was able to shift the focus to others. This book was no longer about me or my mother or my father. It was about the world we live in. By using real life quotes from someone like Trump, Clinton and Fritzl’s trial I was able to offer indisputable truths about the world that girls are born into.

The threads I followed were complex. The poems deceptively simple. Linked in ways that may not be obvious at first. In “swallow”, I am in my early twenties, naïve in many regards, on an island in the Lake of the Woods with a much older, rich man. The reference to the Clinton blue-proof dress and the infamous Oval office blow job intentional, the island reference intentional also, as both Clinton and Trump have been linked to Jeffrey Epstein’s sex slave island. I wanted to show that despite all the work that feminists have done, what happened to me, is still happening.

It took some time to find a way to approach the vulnerability of all women and girls without diminishing the reality that Indigenous women are more at risk. My own experiences offered a way to keep Indigenous women front and centre. Why was I the target of so much sexualized violence is the question behind a number of poems. What did my mother, my father and the world teach me about love, sex and marriage? How are these two things linked? I do not have the answers yet but wanted to invite dialogue, to open a conversation about it all. I am happy to say that although the book was only released at the end of April I have already heard from many women who can relate to some or all of the book.

ROOM: I myself, and I think many poets I’ve read, like to imagine conversations or scenarios with real people whom they’ve never met. Why do you think this is and how do you think this role playing functions emotionally in coming to terms with our subject matter when poets have so many literary tools at their disposal?

JK: As mentioned earlier, it was the U.S. election that really shaped this book and that made me want to add the stories of others. As I began to add those stories I did not think of it as role playing. This is real life stuff and because honesty is such an issue for women I wanted to pursue and offer the ‘truth’ as best I could. I used real life quotes, some from my own life, like those in “a holy hunger”, others are from the news. This is intentional as there are inescapable ‘truths’ in what was said by Trump, my mother, my father or the lover in “a holy hunger”. My ‘imagining’ comes more in the realm of how things feel for others. Even then, I prefer to stay with the not knowing, to leave things open. For example, with “in darkness”, early in the poem I say . . .

her mother unaware

walked over

damp darkness

One could assume the mother’s innocence when they read, her mother unaware, but is that what I am saying? This is left intentionally vague. As a daughter, with a mother that did not protect me from my own father I have questions. As a mother, I can’t help but wonder . . . how could she not feel her own daughter beneath her feet? To avoid moralizing or inviting criticism of the mother I prefer to leave these questions hanging in the air. We just don’t know what she did or did not know or do. I know this not may not be very satisfying but it is what I can live with. Had I tried to ‘imagine’ her life I would have come up short and taken away from the tragedy of what happened in that house. I would have made it fiction when I wanted the stark ‘truth’ of what happened to the daughter and her children to be the focus. Imagining lives can give the reader and the writer a level of comfort I did not want to offer.

I also stayed away from offering the men in the poems a way out. I wanted their deeds and words to speak for themselves and for their complexity to be revealed in the observations of others. In “dark matter” I explore how often people are shocked to find that their neighbor or co-workers were not only serial killers but sexual sadists. When interviewed so many offer the same thing I heard over and over about my own father . . . he was always such a nice guy. I did not want to turn the reader’s attention towards the men and their wounds. This does need to be done. Just not by me at this time. I thoroughly enjoyed Ananaka Schofield’s book Martin John and look forward to each episode of the TV show, Rectify. Both offer us the abusers or suspected abusers side and yes, I am intrigued. Maybe this is something I will explore in a fiction.

ROOM: I know initially when you entered more seriously into creative writing you expected to go the non-fiction route. What aspects of poetry excite you or rock you somehow that keep you coming back to the genre? Is there any aspect to your process that involves other genres?

JK: It is hard to believe that I very nearly missed poetry all together. It is my language. It truly is that door that goes on opening. There is always more. That includes both reading and writing poetry.

I have started to dabble in the creative non-fiction stream and have a desire to move into fiction. There are things I cannot explore via poetry and non-fiction limits what I can say. I think I may have exposed enough family truths for now. I will have a quirky lyric prose piece in the next issue of CV2 and very soon there should be short non-fiction piece up on the Royal BC Museum’s online magazine, Curious.

I do find prose challenging—the writing of it painful—even this interview. I write, re-write, delete the whole goddam thing over and over. When writing prose, I find it hard to be clear and concise. Whereas with poetry, especially the first few lines, it comes staccato-like, slow, steady and succinct. This is not to say that my poems arrive complete. There is always editing, fine tuning, research and/or the need for more unpacking of themes or metaphors but I find all this exhilarating. It is what I live for most days.

Like most writers I find inspiration in all things but find that there is nothing like a good book, be it poetry or prose, to bring much needed ways into what I want to write about.

ROOM: Talking about the world from the outside—of course we’re just one person can only speak from personal experience—but do you think that engaging with other characters in poetry helps to extend a hand to readers? A kind of, “I live in this world too; come on into how I’ve experienced it” proposal.

JK: Engaging other characters can open doors that might otherwise be closed. It can just as easily exclude so one must be cautious when doing this. At this time, I would hesitate to write a poem from the point of view of a sex worker. And even though I am Indigenous I only feel comfortable writing about our murdered and missing women as an observer or survivor of sexual assault myself. In REDdress I speak to the pain we all feel about what is happening in this country. I could have offered more. I have sat in circles with Indigenous mothers whose daughters are missing or murdered. I know intimate details of their story but would never include them in any poem. What is shared in circle is sacred but it is more than that. Why would I mine their grief like that? Enough has been taken from the Indigenous men and women all around the world. Given this I prefer to use the details of my own story and to follow Jaime Black’s lead. Her REDdress installation was visually compelling. I in turn offer the visual of empty red dresses on balconies and at the side of the road as a way to speak to the absence, the ache brought on by the loss of our women and girls.

An Honest Woman was just released last month and, as mentioned earlier, I have already had numerous women and girls reach out to me. Sadly, many of them were young mixed race, waitresses and high school students, who say that poems like, once considered a delicacy spoke to them. They already know how it feels to be the Exotic Other. They know the inappropriate things that some men say and do. And whether these things were done to them via word and/or deed they have already experienced the chilling effects of the silencing that follows. They were relieved to see someone speaking so openly about this subject. They said they felt less alone. That so many have already said they can relate troubles me. That these things are still going on today should concern everyone!

ROOM: In an interview on the Hardest Thing About Being a Writer, you stated of being a writer—“At best it is one-third writing and two-thirds managing your social media presence, doing readings, interviews, writing reviews, volunteering on literary magazine boards, writing grant proposals, presenting on panels, doing manuscript consults and developing and delivering workshops.” This is very true. Writing is a lot of work and requires a lot of work on things that are not our own writing. Do you have any advice for writers trying to find their own balance routines and how to deal with the frustration that comes along with that prioritizing?

JK: Surround yourself with good mentors and writerly friends. I am blessed to have mentors like Betsy Warland and Joanne Arnott. Both have become dear friends. Each has given me insight into how they manage their writing lives. From simple things like Betsy’s suggestion that I schedule manuscript consults in the coffee shop down the street. Such a small thing in one way but the time and stress avoided by not driving in Vancouver have allowed me to schedule more consults than I might have otherwise been able to manage. Why didn’t I think of that?

While discussing whether or not I could manage writing, An Honest Woman, Joanne offered this gem . . . “the best way to sell your current book is to write a new book.” Every time I wanted to give up I would hear her words. It kept me focused. She was right. The release of, An Honest Woman, did bring interest to my first book, page as bone ~ ink as blood.

Both women have walked me through some of the issues that arise as one makes their way through the #Canlit scene. I am so grateful to them both.

As for seeking balance. Writing can be all encompassing. When writing I get up, make coffee, hit the computer. I do this unbathed and in my nightgown. I do not eat. I am unavailable to my husband who knows that even glancing at me, especially if he has a question in his mind, interrupts my process. Yes, I am that precious about it all. But writing of painful things like loss, racism, sexism, sexual assault and childhood abuse is not easy. Self-care is important. So during the ‘writing’ phase I also take time for walks (after I bathe and get dressed so as not to disturb the neighbours). During those walks I pray.

ROOM: Honesty is in the title of your new book, but the notion of “Truth” played a huge role in your first published book of poetry, page as bone ~ ink as blood, which looks at the liminal footing of a woman and living life as a mixed-race woman. For me, you enter into An Honest Woman with more rawness. Is this overhanging theme of honesty—alongside autobiography, and subjects of sexuality, motherhood, and femininity—intentional or is it a filter in your head somewhere that colours your perception in a way you can’t shake?

JK: Yes, it is intentional. Truth and honesty were illusive things in my family and when they weren’t the truth or honesty offered was often damaging. I learned pretty quickly that whoever controlled the narrative had all the power. It was clear that I was not to speak of the violence I had witnessed and experienced. My mother had me to turn to. In some regards she had my father, especially after an abusive incident when they would enter the honeymoon phase. During those times I had no one as my father demanded all her attention.

That she turned to me for solace has no doubt coloured my perception of sex, love and marriage. It also made me the target of my father’s rage. His rejection of me left me vulnerable. I entered an unsafe world, mixed blood Indigenous, unprepared and alone. What happened next was a continuation of what happened in my home and no matter what men did to me, it was always my ‘honesty’ that was always questioned. That I was not allowed to speak to what I witnessed or experienced has always troubled me and when I found poetry I found a way to circumvent the censorship that existed in my family and this insanely patriarchal world.

ROOM: I personally find your writing to have this quality of hospitality, like after a hug that says everything and you’re left feeling really bare, with a poem that I can’t condense into a word but a feeling instead. It’s very intimate. I appreciate your honesty and openness so much. An Honest Woman, “confronts us with beauty and ugliness in the wholesome riot that is sex, love, and marriage.” How do you personally formulate writing about sex, marriage, and love—issues that come to us all at some point or another and demand we face up to our feelings about them? As well, how do you approach the self-care it takes to confront those memories which can be so emotionally draining?

JK: The feeling of a hug is intentional. This is painful, close to the bone stuff. I am aware that my readers may also be survivors or that they may not have been this close to anything of this nature. News sound-bites about things like the MMIW and the Fritzl case are one thing but to read a poem intentionally designed to offer visceral moments of terror or to explore the loss of sovereignty experienced with sexualized violence is a whole other thing. Given all this I do my best to offer ‘just enough’ so as not to overwhelm my reader. There are still things that have happened to me that I may never share with anyone. This is done out of respect for the sanctity of their being. It is hard to ‘unsee’ or ‘unhear’ some things.

Having said all that, the truth is that I have no choice in what I write. These things push on me, demand my attention. This has been so since I was a young child. Not the writing but the need to explore what happens when men and women try out sex, love and marriage. I remember being in elementary school and deciding that marriage sucked for girls. I used my bleeding eczema fingers to avoid high school typing classes because I was not going to be any man’s secretary. I was a teenager when I started to feel the rules for men and women around sex were not fair. Why did I have to be a ‘good girl’? And why was my desire dirty and his not? I still have so much to say about all of this but started with what I could manage. That decision was an act of self-care. It is not easy to dip back into the pool of murky water that most survivors find themselves in, endlessly treading water, hoping to not drink the dirty water of betrayal. I left those waters long ago. Returning was not easy and it required lots of self-care. Time alone was important but only went so far. With, An Honest Woman, I had many serious fibromyalgia flares and decided to return to therapy. But this time I chose somatic therapy with my beloved Continuum teacher, Doris Maranda. I still have the ball of red thread that we used in an exercise around the need for boundaries. It sits on my writing altar as a reminder of our time together and the need for good boundaries in life. Something I am still learning to put in place and maintain.

ROOM: Do you have any advice to give those who will be submitting to Room’s poetry contest regarding what you are looking for in a strong submission?

JK: Yes, trust yourself. Let your fingers fly. Bring me words that burn holes in paper. String them together in creative ways. Be fearless . . . be fierce—or be tender. Whatever you choose throw yourself into it. Trust yourself. While in the rough draft phase I rarely think of my readers. I write for the sheer joy of it. Bring me what brings you joy! And yes, I do find joy in writing about difficult things like sexism, racism etc. There is no greater feeling than reading or writing a piece that upends the world we live in. Go ahead be cheeky. Show me—tell me how you really feel about things. Offer me a love poem, a rant . . . whatever you feel you would like to have others know about you and the world you live in.