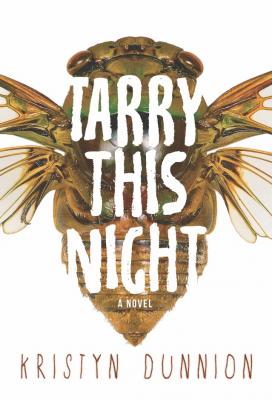

In a world not unimaginably different from our own, members of a religious cult wait out a civil war in an underground bunker. Tarry This Night, Kristyn Dunnion’s second novel, is an unsettling tale told in turns by five members of the Family, including Father Ernst, the sect’s once-charismatic polygamist leader.

In a world not unimaginably different from our own, members of a religious cult wait out a civil war in an underground bunker. Tarry This Night, Kristyn Dunnion’s second novel, is an unsettling tale told in turns by five members of the Family, including Father Ernst, the sect’s once-charismatic polygamist leader. Set in a not-so-distant future and broaching many of the themes currently in the news—political polarization, nuclear warfare, gender inequity, religious extremism, climate change—this carefully crafted, suspenseful novel is a reminder of just how awful things could get if we don’t get our act together.

Tarry This Night is a study in tunnel vision—or rather, bunker vision. In the dim, dank shelter, the Family is literally and figuratively in the dark as they await the “Ascension.” The narrators share a limited understanding of themselves, their fellow inhabitants, goings-on “topside,” and the doctrine they purport to follow. Reverent and dutiful Cousin Ruth pines for her brother, oblivious to his feelings for another Family member. The curmudgeonly Mother Susan disavows “hussies,” but succumbs to her own private desires in the dead of night. For Mother Rebekah, hopelessness becomes a kind of tunnel vision that leads her to take devastating action. Here, the use of several third-person narrators has disparate effects; while the reader has the advantage of more than one perspective, Dunnion’s restrained hand invokes the feeling that we’re never being told everything. Indeed, the Family’s role in causing the above-ground conflict is lightly sketched, and never explained in full, which might have detracted from the present-tense action.

This restraint pays off in the second half of the novel, as a macabre turn of events leads to an awareness the characters have been missing. Among the narrators, Cousin Ruth and Mother Susan undergo drastic but believable transformations, driving the interrelated narratives to their singular climax.

Dunnion is at the height of her powers when describing matters of the flesh: blood is “metallic heat,” burn wounds “pussed and frothed,” Rebekah’s wrists are “delicate bird bones.” Father Ernst is physically repulsive, with his unwashed skin, “pouchy eye,” and moustache, which “parts to yellow teeth.” If this novel has a single failing, it’s that it’s too short. I would have liked to inhabit Dunnion’s chillingly drawn world a little bit longer, especially toward the end. But unlike her characters, who must wait for the Ascension in darkness, Dunnion never tarries, making for a fast and consuming read.