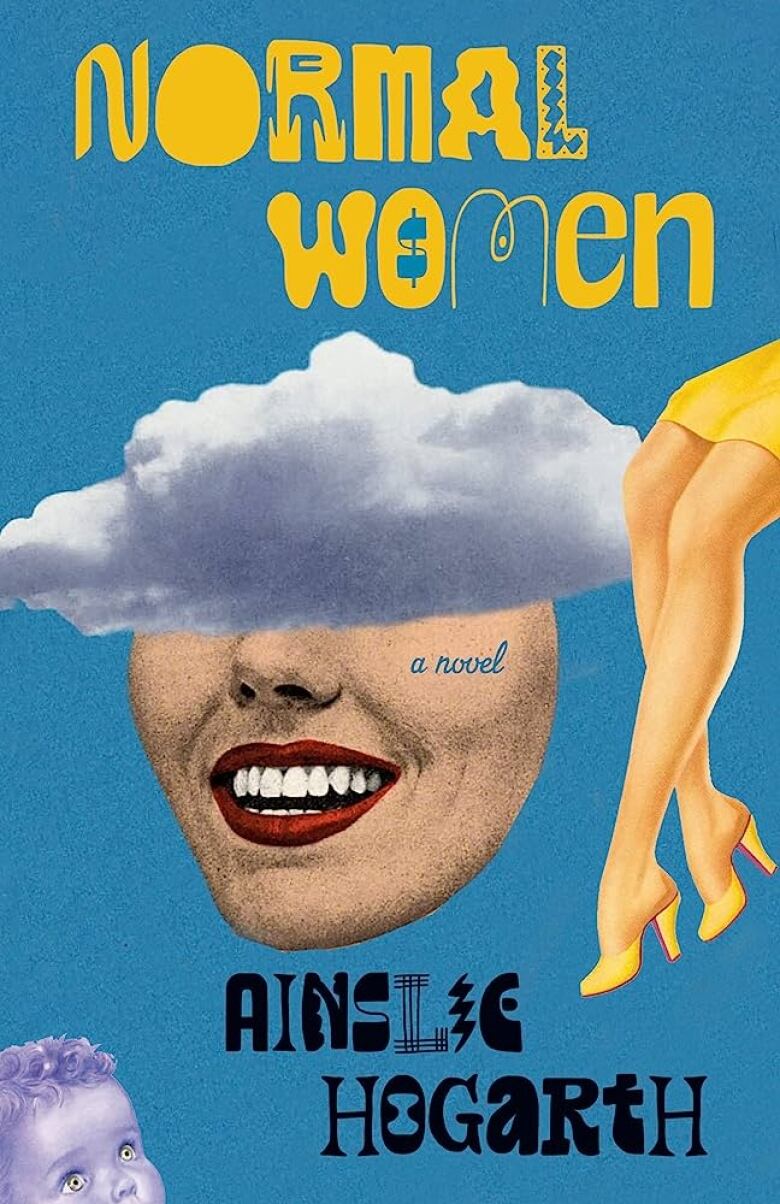

Room’s winter issue 46.4 FEVER DREAM is open for pre-orders until Dec 15th. Gracing this issue is Ainslie Hogarth’s commissioned story “Bad Egg,” a story about power, obsession, and two characters alone in a mansion during an apocalyptic storm. While you wait for FEVER DREAM to arrive, here’s an excerpt from Ainslie’s latest novel Normal Women (Vintage Anchor, 2023).

Normal Women, is a dark, literary comedy about how we value female labour—and how we don’t. When her daughter Lotte is born, Dani welcomes the chance to be a stay-at-home mom. To be good at something, for once. But now Dani can’t stop thinking about her seemingly healthy husband Clark dropping dead, not because she hates him (not right now anyway) but because it’s become abundantly clear to Dani that she doesn’t have any viable way of earning a decent living. If Clark dies, she and Lotte are screwed.

Normal Women – An Excerpt

They’d been living in the city when they found out Dani was pregnant. A condo: one bedroom plus a pitiful, windowless den, and a whole closet taken up by a washing machine and a dryer. They looked at a few houses in their neighbourhood and beyond, almost all of them near dangerously run-down, hastily disguised in fresh paint and pot lights and still well out of their price range. They decided to revisit the matter of their inadequate housing after Lotte was born. Maybe it wouldn’t be so bad having an infant in a 700-square-foot sock drawer, sixty feet in the air.

“We’ll make it work!” Clark declared, with suspicious optimism. Almost as though he’d already known about the promotion he announced six months later. The real estate development company he worked for was opening a new office. In Metcalf, of all places. Dani’s hometown. An area positively booming thanks to the grand re-opening of the Silver Waste Management Corporation (now known as the Silver Waste Management Campus, or SWMC around town) where innovative approaches to managing garbage had attracted a haughty crowd of environmental consultancies, AI think tanks, and tech start-ups, which, all together, began to resemble what people like Clark called a hub.

Naturally, the coffee shops appeared first. With a hermit crab’s entitlement, they began occupying the criminally small cubby holes that developers like Clark carved from crumbling strips of brick storefront. They sold cortados in short brown cups and hot new literary fiction and austere notebooks and expensive espresso machines which would collect dust on the counters of hectic businessmen, checking their teeth for sesame seeds in the chrome dash before zipping out the door to grab a cortado before work.

And then there were the taco joints with take-out windows and vegan carnitas, where you could buy a jar of homemade salsa for $10, queso for $12.

And that pizza place with the graffiti walls and COWABUNGA signature pie to appeal to nostalgic millennials, the former Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle fans spending a fortune on real estate and nacho dips.

It was Dani’s father who’d started the original Silver Waste Management Corporation. Daniel “DJ” Silver, the garbage king of Metcalf, even back then a sizeable kingdom of waste-processing innovation. At one time he employed almost the entire town, made more money than any single man could know what to do with or spend in his life. He sponsored little league teams and bought decadent dinners for the soup kitchen every holiday; he supplied public schools with sports equipment, bought a trampoline for the musty downtown Y. There was a fountain named after him, his portrait above a plaque in City Hall, and tales of his famously humble beginnings nurtured false hope in underprivileged children all over the county.

For a long time Dani didn’t know they were rich. She grew up in the same drafty old farmhouse her father had, where her mother still lived: a basement besieged by warm blooded vermin, cold air gushing between warped bones. No one with money would have lived that way. But they did. Thirty years ago this unnecessary suffering signaled proof of DJ’s fine character; today locals thought Dani’s mother, Bunny, should feel ashamed to still be there—the woman who’d squandered his fortune, carrying on, unpunished, in his beloved family home.

Metcalf.

Dani squished her eyes shut.

Metcalf.

Clark sensed her reluctance, feelers sharpened by his trade. He leaned forward, slid his fingers between hers. “I know,” he said, forcing his way into her eyeline. “Trust me, I know. But Dani, you’re not failing by going home. Quite the opposite. Honestly that the idea of going back home has somehow been warped into failure, that’s got to be, I mean, I don’t know, you’re the philosopher, but that’s got to be by capitalist design, no?” Dani raised an eyebrow; he pressed harder. “Unmooring us from ourselves, our roots, making us wary of such easy and inexpensive peace. Boosting the illusion of this endless journey, endless growth, all so we can buy our idea of home instead. Create the void, then fill the void, right? You know, all that stuff. Look, the fact is, this is a huge promotion. And a fuck ton of money. The signing bonus alone is basically our down payment on a house. And you won’t have to work again at all if you don’t want to. You could just be with Lotte.” He drew a long, meaningful look at her stomach. She rolled her eyes and shook an offended whinny from her snout as she tipped big, jiggling curds of scrambled egg onto their plates. “Except I don’t want to just stay home with the baby,” she said, setting the pan on the table and docking herself in her seat. At almost seven months pregnant Dani’s belly was no longer even remotely adorable. She was a big, sweaty spectacle. Ample. Enormous. A reluctant god: crowds parted for her on the sidewalk, bus seats materialized out of thin air. She accepted these grand genuflections hurriedly, without eye contact, hating every second of it, but not wanting to seem ungrateful. She snatched a bite from her toast and left the crumbs where they landed.

Clark sat down across from her. He picked up his fork, speared a cherry tomato, glittering with salt, and pointed at her with it. “You know I didn’t mean it like that.” He slid the tomato off his fork with his teeth.

Clark didn’t know what he was talking about. He had no idea how he was supposed to mean it or how he wasn’t supposed to mean it. He knew he didn’t want to seem like a man who would prefer his wife to stay home with his child. He knew that.

And Dani didn’t really know what she wanted. She should feel proud to be a stay-at-home mother. She should feel lucky. It’s the hardest job in the world, that’s what everyone always said, and though Dani was sure the work itself was indeed very difficult. Extremely difficult. Possibly much more than she could even handle, she suspected that what made the job even harder was the utter lack of respect a person got for doing it, from assholes like her.

It wasn’t completely preposterous for Clark to have made this suggestion, either. On the advice of the forum mothers, she’d put their unborn daughter’s name on all the daycare lists within reasonable walking distance from their condo—Six months pregnant? Girl, you’re already too late!—And then cried on and off all night picturing some aromatic administrator pulling Lotte screaming from her arms, fists full of Dani’s jacket, refusing to let go, cortisol boiling scars into her as yet unmarred brain, all so Dani could, what, return to another pathetic office job? Some insignificant little company, disseminating worthless digital content for very little money, where the only thing she did with any care at all was ensure she was out the door at exactly 5 o’ clock. Maybe if Dani were a human rights lawyer, performing good work for those who needed it; a dentist, securing a sound financial future for her family. Even if she simply enjoyed her work, at all, it might be different. But none of those things were the case. Despite identifying strongly as a feminist, Dani didn’t have a career. And while maybe she could technically be a feminist without financial independence, having to ask Clark for money certainly didn’t feel in the spirit of the thing.

“I just…” she prodded her scrambled eggs with her fork, struggling to come up with a reason they couldn’t move to Metcalf, but everything she thought of withered against the argument of more money, cheaper housing, her mother nearby. Anya. Her oldest friend. Probably still her best friend, really. “I’ve just got a bad feeling Clark, about moving to Metcalf, I’ve got this,” she swallowed, “I’ve got this,” she swallowed again, “gulp-resistant lump in my throat. Honestly, it’s not going away,” she gulped, audibly, putting her neck and shoulders into it, making it hurt this time. She raised her fingers to her throat, pressed gently, feeling for the sea urchin that must surely be lodged there.

And Clark, a good person at the moment (sometimes he was a bad person), honoured her nebulous dread, he raised the fingers not currently occupied by cutlery, a calming gesture, and cooed, “I understand. I really do. It’s different for you, to go back home, you’ve got your…legacy.” Dani winced. Embarrassed. It was fine for her to secretly believe she had any kind of legacy in Metcalf, but she didn’t want anyone else, even Clark, to know that she felt that way. If she did have any legacy, her continued absence was all that sustained it—a generation of Metcalfians who knew her once the way she was, paused from time to time to wonder whatever happened to that Danielle Silver? Where did she get away to? And the possibilities endless. Because she’d been royalty once, the Princess of Trash, now vanished without a trace: A kind of Anastasia Romanov. A Garbage Anastasia Romanov. If she returned now, they’d know exactly what happened to her: Whatever happened to that Danielle Silver? Oh, I just ran into her in the mall actually, she was in line at Kernals, yes, just waiting her turn to purchase a small bit of popcorn, yes, a little treat for herself, yes, she deserves a little treat. That Danielle Silver? She lives in one of the cozy pre-wars near the creek. She got married, yes, had a baby, yes, just the one, yes, and now stays at home to raise her just like the rest of us. Yes. She stays at home. With just the one. That’s right, just the one. Just like Bunny. More like Bunny, it turns out, than DJ. Away from us, we hadn’t known. Away from us she might have been anyone. But back home we see, we all see. Her mother’s daughter, through and through. Too bad. Really too bad. We could have used another DJ Silver. Remember the feasts DJ Silver put on at the soup kitchens? Remember the graphing calculators he bought the remedial school? And my god, remember that trampoline? I don’t know any kid in this town who didn’t just come alive on DJ’s trampoline.

Dani closed her eyes. Listened to the gentle ruckus of Clark’s utensils against his plate. Toast shattering between his teeth. “Nothing’s happening yet”—his voice muffled by food. “It’s just an offer for now, something to think about. And if I don’t take it, we can figure something else out. The condo’s not so bad for now.” He swallowed. “We’ll make it work!”

Dani nodded, closed her eyes, rested a hand over her belly.

“Are you okay?”

“Yes,” she exhaled. “Just kicking.” Lotte pounded her legs, dragged against the fleshy upholstery of her uterine perimeters, the slow, exploratory pace that Dani already understood to be part of her personality.

Metcalf.

Moving to Metcalf.

Because Dani didn’t really have a choice, did she? Clark was acting like she did, because of course, once again, he knew he didn’t want to seem like the kind of man who allowed his salary to influence the power dynamic of his marriage. But of course it did. And they both knew it. The money had made a decision. And Dani would go where the money went. So she opened her eyes, found Clark innocently wiping yolk from his plate with his last scrap of toast, awaiting her approval like a very good man, like a man who would have halted his career based on the vague anxieties of his nervous little wife. At least this way she could feel as though she had some control too. Better this way, wasn’t it? She shuddered, fighting off a hazy picture of the alternative: how it would look to do away with the performance all together. Dani swallowed the sea urchin with wincing effort. And agreed to move back to Metcalf.

That night Dani sweat through the bedsheets, Lotte thrashing inside her like she never had before. A protest. A warning. The princess of trash returning to her kingdom. The king dead. The queen insane. And Lotte the trigger to some hellish prophecy that would destroy them all.

If Lotte could have known Dani’s thoughts that night, the way she’d be able to in thirteen years or so, with all her teenage powers, she would read her mother with the precision of a surgeon, hormone-mad, sociopathy laser-focused on the pathetic host she’d shed like snakeskin. The way it ought to be. The way it had been since mothers started having daughters. Wow, Mom, do you really think you’re that special? That you’ve been in anyone’s thoughts at all? A hellish prophecy for god’s sake? It must be exhausting, honestly, to be so fucking bored. And even Clark, accustomed by now to Lotte’s casual cruelties, would wince at that one, barely exhaling the word daaaaaaaamn as Lotte turned and left. Levelled up. Mother eviscerated. Eviscerated, but also, secretly, sickeningly delighted. Because finally Dani knew, once and for all, a gift from her daughter, exactly who the fuck she was.

_____________________________________________________________________