Room editorial board member Jónína Kirton talks to our Cover Art Contest judge Amy Friend about her beautiful and haunting art.

One of Room‘s Cover Art contest judges, Amy Friend grew up on the outskirts of Windsor, Ontario, Canada where the Detroit River meets Lake St.Clair. She studied at OCADU (Toronto) before embarking on intermittent travels through Europe, Africa, Cuba, and the United States. Upon her return she continued her studies and received a BFA Honours degree and BEd degree from York University, Toronto and an MFA from the University of Windsor. Currently she teaches Fine Arts at Brock University in St. Catharines, Ontario. Friend has exhibited nationally and internationally, including exhibitions at the Galerie Riviere/Faiveley (Paris, France), Cordon/Potts Gallery (San Francisco), Houston Center for Photography, Photoville (Brooklyn, New York), 555 Gallery (Boston), Onassis Cultural Center (Greece) and is participating GuatePhoto, Guatamela in the Fall of 2015. Room editorial board member Jónína Kirton talked to her about her work.

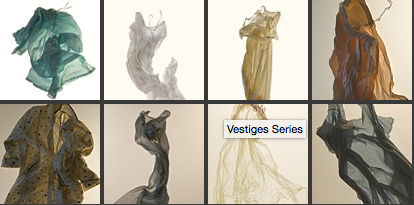

On your website you say that “the deceased occupied a place in our home”. This seems to be a common theme in much of your work. In the Soon This Space Will Be Too Small series you have photographed some of your deceased grandmother’s clothing including her nightgowns. These photographs appear to capture what some might say was your grandmother’s residual energy. It is hard to believe that one could capture that in a photograph yet you managed to do this. How did you come to this project?

Growing up, my Nonna (Italian grandmother) only lived two doors away and when my grandfather passed away she basically lived with us. She lived to be ninety years old. She was from the generation that lived through the depression in Canada, so she kept everything including these old nightgowns. We would lovingly make fun of her because she would wear the same outfit every single day until it wore out. Much of her clothing had marks where her large breasts had rubbed. Her sweaters were threadbare, the elbows worn out. I loved the idea that her physicality remained in the clothing. Her nightgowns were marked in a very different way because they captured the movement of her sleep. She slept on her left side so the nightgowns were threadbare on that side. The nightgowns reminded me of a photographic negative because it was as if her body had translated through light to a surface. What I wanted to do was capture the presence of her body via photographs of her clothing. I tried to accomplish this in a number of ways but I was not very happy with the results, so I began to literally talk to the garments. This might sound crazy, but I asked them what they wanted from me. Through intuition, I understood that they simply wanted to be free. I decided to build a very large light box—about twenty feet by twenty feet—angled it and lit it from behind. I would climb a ladder and drop the nightgown so that they looked like they were floating. I literally tossed them in the air and let them land as they wanted.

The results were incredible. Was it healing for you to do this with your grandmother’s clothing?

It was actually quite healing. I even decided to use the nightgown that she had passed away in. The ambulance attendants had cut it wide open so it looked like these beautiful moth wings. I think that I look at death differently than many people. Her death was of course very sad but it was also incredibly spiritual at the same time. I feel that death is something that we need to embrace rather than run from. A lot of my work weaves in and out of this idea. It is something that I always come back to. I tend to work with the idea of polar opposites, life and death, light and dark, the spiritual and the real. To me a photograph is both real and spiritual.

The photos in your Dare alla Luce series (featured on the cover of Room 36.1) are a good example of the real and the spiritual. They have an ethereal quality. You indicate that the name of the collection is Italian and means, “to bring to the light”. This seems to be a very appropriate title for this series. Adding the light to the photos appears to have made visible what was not. It is as if you have captured the spirit of those who are featured in the photos. How did you come to this project?

The photos in your Dare alla Luce series (featured on the cover of Room 36.1) are a good example of the real and the spiritual. They have an ethereal quality. You indicate that the name of the collection is Italian and means, “to bring to the light”. This seems to be a very appropriate title for this series. Adding the light to the photos appears to have made visible what was not. It is as if you have captured the spirit of those who are featured in the photos. How did you come to this project?

I work quite a bit with lost narratives. I began to work with my Nonna’s old photos. Looking through them I realized that there was all this history and for some reason it had been put away and not shared. I thought it was really sad that it was possible that no one had wanted to hear her stories about the photos. Many people in the photos were people she knew before she immigrated to Canada from Italy. I wondered what part of Italy they were from, what was their experience coming over, or if they stayed in Italy, what was it like watching their family and friends leave. She would tell me bits and pieces. I found it fascinating. Later I asked my mother “Did you know that they (my Nonna) raised silkworms to raise the money to leave Italy?” And she said, “No, I had no idea.”

This surprised me as my mother and my Nonna were very close. It was probably more about timing as I do think that there are times when people are ready to tell their story. I might have simply been there at the right time.

As my Nonna shared her stories I became increasingly interested but I also found myself thinking about what we didn’t know about the people in the photos. I think photography can be very deceptive. On one hand it presents you with a fragmentary picture of existence but it is just one tiny moment in a life. Even with this knowledge we often read photos as if they are a novel.

When did you realize the hidden potential in these photos? How did that come to you?

I had worked a lot with images from my family’s album. At first I only worked with the photos that I knew something about but then one day it occurred to me that it would be interesting to step aside from that. I decided to pick photos of people my grandmother had forgotten, and who were complete strangers to me, to see how I responded to the images. I wanted to explore what it means to have some one else’s photograph? I found that every time I approached the images I would feel this sense of loss. As I contemplated this feeling I realized these pictures did not have a proper home, a proper place or a proper preciousness.

I think that photos like these are a sacred remnant and that they have a spiritual quality to them. I wanted to bring that thought more to the forefront, to find some way to reclaim their preciousness, not leave them tossed aside in a box.

I also think that the way we interact with photographs is dramatically changing. Some of my photography students have never printed a photo. I think we are more disconnected from the images that we view on a screen and that we miss something when there is no tactile experience. With these thoughts in mind I began to sew on my found photos. It was very time consuming process; I would take them to my husband’s baseball games and work on them while he played. For a time I was the crazy lady in the stands sewing on vintage photos. Then one night I was doing this and just as the sun was setting I held the images up to the sunlight and the light came through the holes that I had already punctured into the imagery and I thought this was so much better than what was am doing with the sewing. It was accidental discovery.

Such a “happy accident.”

Yes, I had known something wasn’t quite right with the embroidery. The added light in the photos was so much more interesting to me. Light is an important component in my work and I was happy to discover yet another way to work with it. I shifted away from embroidery to simply using the punctures to bring in light, which I felt brought the preciousness I was hoping to reclaim for these photos and those featured in them. It also referenced the nuances of photography, which I like to do in subtle ways in my work.

Your work has a spiritual quality. You seem to touch the ethereal with such ease. I feel you are comfortable there. Are there any rituals that you use as you enter the work?

Well, my studio is an actual disaster. I try to clean out the previous project before moving on to new work. Interesting, that you would ask this as the Dare alla Luce work keeps pulling me back, which means that I have not been able to put it aside. Given this, I am having a hard time getting into my next series. When I start something new I also like to do space clearing. I get my sage out. I try to take different objects out of hiding, which I have saved. These objects are often what sparks connections within the work I am making. I am currently working on a new series soon to be exhibited. The exhibition, which will be at Rodman Hall in St Catharines, ON, is titled Assorted Objects of Ordinary Life, and it opens in January. It’s curated by Marcie Bronson.

Can you tell us a little about this new project?

I am working with a tiny box of possessions from a distant relative that had passed away. Prior to his death, he had become ill. Hearing about his misfortune, my father said, “We need to take care of him.” Getting to know him we found out that he had married late in life and had no children. We learned that long ago his wife had gone in for a routine surgery and that she had left him a note saying, “It’s the big day. If anything happens the insurance papers are in this drawer.” Sadly, she died that night. Apparently, the hospital called him and said, “You need to come in. Your wife has passed away.” He did what he needed to do at the hospital went home and removed all forms of communication, telephone, television, any news media, he had no radio. He would go to the bar near his house to watch the ball games.

The box is a curiosity, as we really know so little about him. I know that he was in World War II and that he worked at a factory for twenty or thirty years. I treat the box and the objects in it like a story that I am unravelling. Not just a story about this distant relative, but also about all of our lives and that one day we will all be reduced to absolutely nothing. We will be dispersed. I find this fact both sad and yet strangely beautiful.

This project sounds, in some ways, like a continuation of the theme, “the deceased occupied a place in our home”. It seems that family often plays a central role in your work. Growing up, how early was it apparent that you were artistic?

I have always been interested in the arts. I think all children are naturally creative. I grew up in a household where people were always doing something creative. Not always visual art, but definitely creative. For example my grandfather built a round house where I spent much of my youth. It was like a castle, which sounds really elegant but it was more interesting than elegant. My grandfather was a builder. He would tear buildings down and recycle the material. When he left Italy he travelled through a number of countries and on his journey he saw a castle. He said “I’m going to build myself a castle one day”, but it actually looked more like a lighthouse than a castle, as it is one round or rather cylindrical structure. The top floor had a terrace overlooked the second floor, where there was a kitchen. We would often run around that terrace. It had a 360-degree view. It was beautiful.

We were always doing something whether it was cooking strange meals or trying to use whatever materials we had to make something. I was a quiet kid. I liked to be left alone to do my things. I always felt like I was making something. My parents were great. Anything I wanted to do was okay with them. I was also very active so played all sorts of sports. Once done with sports I would go to my room to paint and draw. I first practiced photography in high school when they had a dark room. I still like to think that something sparked way back then.

What is the most interesting day job that you have had and did it bring anything valuable to your photography or art?

That is hard to answer, as I tend to not think very much about my own life when I approach my art making or at least that is how it seems to me. In my work it is about my experience of other people’s lives. My parents owned a number of businesses. Some were successful. Some not. They had a donut shop, which I worked at as a young teenager. We had all types of characters coming in. We had lonely coffee drinkers, and many regulars who would come in and in advertently share much about their lives. I ended up putting myself through school working in restaurants. I never did work at any art related jobs until University.

Sounds as if you have been gathering stories your whole life. You have received a number of awards and grants. Would you like to speak to the importance of this for artists?

Yes, I am quite passionate about this subject. I am grateful for the grants that I have received. Grants are paramount to being able to make the life of an artist work. I could not have done it without this support. I am also aware that far too many artists and artistic endeavours are underfunded. Creating art of any kind takes time and in many cases the tools and equipment are expensive. I think it is important for artists to not only be recognized for their work but also for others to understand the realities they face, that in many ways they enrich the lives of others and add to the economy.

Yes, being paid or compensated in some way for the work one does is important. Frequently, we are asked to donate our art for good causes often with the promise of some exposure.

There are times that I am able to help but simply cannot donate to every cause. As artists we often undervalue ourselves. In the end I want to share my work, but I also need to be realistic and feed myself and my family. Occasionally, I have come across people who do not seem to understand that this is my profession. I have had my work used without my permission.

How do you protect the work that is on your website?

I don’t. It is impossible. You can try. There are times that I like that my work is out there and the fact that it is being shared with a broader audience. I have however asked people to remove my work because I don’t like the way it is being portrayed or if they are blatantly using it for another purpose. But in the end I really look at it this way, it is the Internet after all.

You have a new exhibit that combines poetry with photos. Can you tell us a little about this one?

Yes, it is called Black, White and Read. “Read” being read as “Red”. It’s an exhibition at the Cannon Gallery of Art at Western Oregon University, curated by Robert Tomlinson and Paula Booth. Black & White & Read is specifically an ekphrastic photo/poem exhibition consisting of 15 black & white portraits of women by 15 different artists and poems written in response to the images by 15 different poets. There will also be a catalogue of the exhibition available. I believe it will be travelling to a number of different universities in the U.S. I have always been interested in the layers that text brings to the visual and vice versa.

We are so excited that you will be our cover art judge. Do you have any suggestions or particular things that you like about cover art? What do you look for?

When I have a piece of art out, for example, in my living room, I want to want to look at it for a while. It is great to have a cover that might be very attention grabbing but more importantly is it something that I am going to want to look at again and again or is it that cover that you end up tucking away. It might be “cool” but I don’t want to look at it every day. Its it something that has potential to be universal? That is quite difficult to achieve but I would appreciate work that can be appreciated from several vantage points. Does it have layers of meaning and is it open enough to allow for a flow of interpretation.

Room editorial board and collective member Jónína Kirton, a prairie born Métis/Icelandic poet and facilitator, currently lives in the unceded territory of the Coast Salish people.