Reading Elizabeth Mudenyo’s collection With Both Hands, feels as if I must be holding an enormous volume—the potency of each poem makes the chapbook feel like a full meal. Guided by the lines of her work, Elizabeth Mudenyo and I discuss Black rest, intimacy, strange routes to self-acceptance, wishes for our loved ones, and what anti-Black racism must look like from a bird’s eye view.

Pushing the expanse with both hands

the black ecstatic

takes me in

opens up

recognizing its kin

(From the poem, “For My Mom, Who Looks At My Hands,” Elizabeth Mudenyo)

ROOM: The line “with both hands,” appears twice in the collection. What does it signify for you?

EM: It’s a recurring phrase in my work, and has come to mean a lot of things. Holding something half-heartedly you’d do with one hand. But if you really want something, to claim it, you’d take it with both hands. When this line appears at the end of the book, it’s about expansion and pushing. A lot of this chapbook is about permissions and entering oneself. Part of that is pushing away the smallness, letting myself be big.

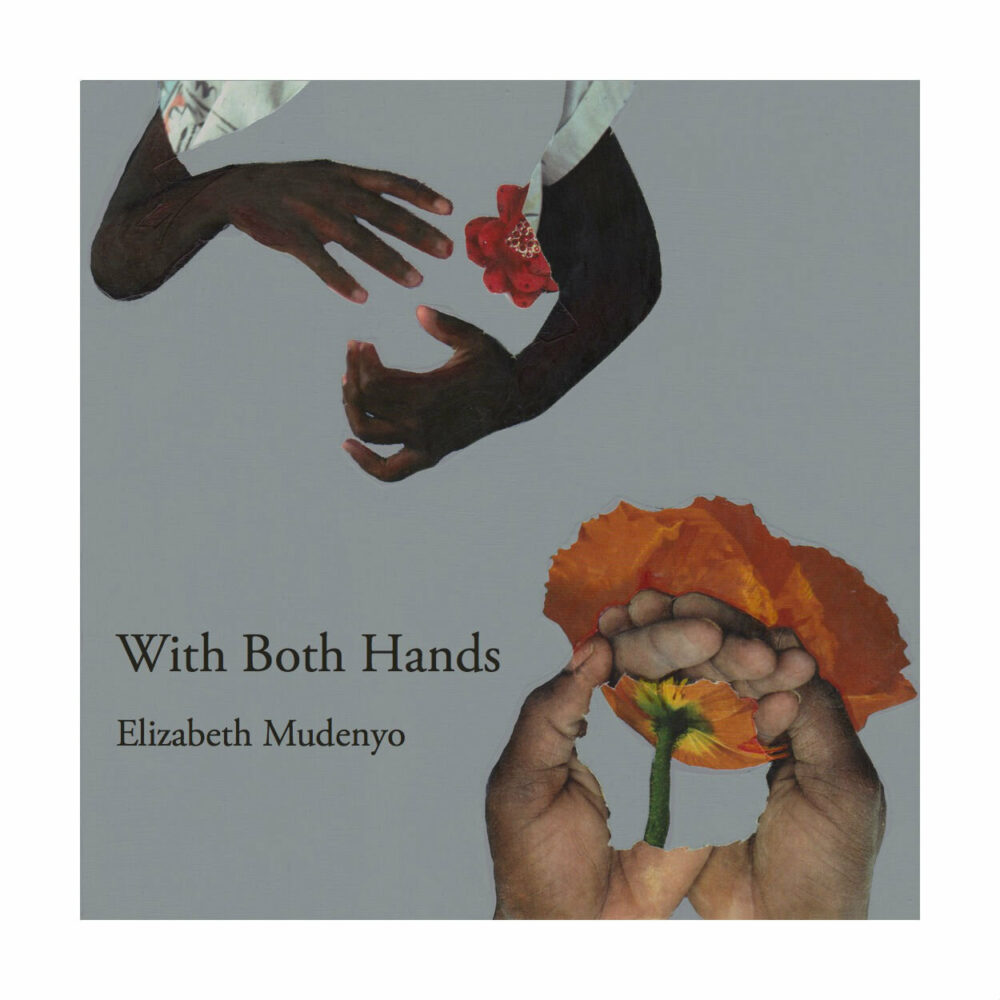

Cover art by Nadijah Robinson

ROOM: “For My Mom, Who Looks at My Hands,” is such an intimate poem. And there was so much physical intimacy in the work.

I love how she says her own name /

with the full weight of her body

(“About Her,” Elizabeth Mudenyo)

ROOM: These lines build with a beautiful reciprocity between the person that’s being looked at, and the person who is looking.

EM: The subject is allowing herself to be perceived. There’s a sort of recognition of this power that bonds her and the speaker. It’s also about acts of reclamation and how we talk to and about ourselves.

ROOM: It sounds like a source of self ownership, at a time when so many of our names are in other people’s mouths.

Sometimes only our bones stand in defense

and hold up the necessary dressing

Sometimes the smile is just rehearsal

for when the soul comes back full

(“When Told to Be Strong,” Elizabeth Mudenyo)

EM:You know, it’s ideal when you are trying to work through an emotion and you can turn to a poem. This one definitely came out of depression-disconnect. But it does imply that you will be full again. There’s a way for our bodies to propel us into survival.

ROOM: Are you ready to talk about “HANDS UP”?

EM: Yes, yea.

We will not lower our hands. We will not be given time

enough.

Count sheep. Imagine clouds looking down at us.

And how they must make us out as animals.

(“HANDS UP,” Elizabeth Mudenyo)

EM: I think when I wrote this poem, it was the day after a Black life was lost to police brutality in 2018. At the time, I was in a writing workshop and I was very much using poetry to process. This poem pretty much came out in the order that it exists.

To me, there is an ideological shift between the two stanzas of the poem. The first, “we will not lower our hands, we will not be given time”—was directly to and about Black communities, and how it feels like we don’t have respite between protests. We’re almost frozen in that moment.

And then the shift in the second stanza is towards the surreal and obscene nature of how Black deaths are orchestrated and consumed. So I started writing instructions, “Count backwards from a hundred. Count sheep. Imagine clouds looking down on us.” Even [clouds] could perceive this cruelty.

ROOM: There’s an abrupt turn towards references of nature, and then at the end a return to the insidiousness of what we are seeing. Laying under the sky is the sort of thing that should feel like freedom. But what is shown to us from the bird’s eye view is something different. This poem is absolutely brilliant. I’m going to sit with it a long time, and keep coming back to it.

‘We can all live here,’ I say to every part

‘You can stay.’

I am again, done with my body.

People are absorbed through pores all the time

(“Permissions,” Elizabeth Mudenyo)

ROOM: We’re turning again to the body in “Permissions.”

EM: I think when I started the poem, I wanted to recognize this barrier to self-acceptance, and self-love. I was like, okay, give yourself permission on the page. You know when you go in, and you’re like ‘I’m going to write a joy poem!’ and then it really doesn’t work out that way, haha.

I guess this is a recurring theme—the way someone else’s gaze or validation can help you see yourself. It’s definitely not healthy. But maybe it’s another way to access yourself.

ROOM: Yea, we don’t always get to find self love the way that we’re “supposed to.” There’s so much about ourselves, our abilities and value, that we don’t believe until some sort of external validation makes it clear. It’s interesting to give oneself permission.

What is it about the distance where bodies are only about wanting

(“Scraping,” Elizabeth Mudenyo)

EM: This is secretly one of my favorites, and I like that [this poem] landed on the spine [of the book] because it is the most vulnerable poem. It actually came from a Danez Smith workshop called Finding Honey Within the Rock. It focused on how we bring some sort of salve or balm to the things that make us feel shame. So in response to this prompt, I thought, let me try to write this poem. But then, I think all of my pandemic poems have this element of touch. That line is very literally about sexual tension.

ROOM: Yea, I was certainly blushing in several poems. There are a lot of erotic elements to this collection.

If it sings,

carry it ‘til the end

(each crooked note)

We take joy

with both hands.

(Clear Throat (Let Us), Elizabeth Mudenyo)

ROOM: This is the poem that struck me the most.

EM: I use language more figuratively in this poem. I think what I am trying to ask myself is ‘what’s prompted by fear and what’s prompted by love?’ And “carry it ‘til the end” is saying don’t let this feeling of joy, or ecstasy, if it feels good, be obstructed by doubts and fears. The line “each crooked note”—reminds me it doesn’t have to be this beautiful thing, let the expression exist. I sometimes have difficulty communicating and this speaks to that permission to sometimes just let it be ugly. You’ll see what it is when it’s in front of you. Let it come out of you.

ROOM:There’s another line I love—“until we blush like the first blot on a canvas.”

EM: That’s a newer line. I’m grateful that it could be new and still speak to the poem. Because it’s new, I’m also still so excited about it. You know, you’re like, I’ve read this poem 20 times, but this part of it I’ve only read five, haha.

ROOM: Yeah, I think I’m gonna read this poem over a lot. Most definitely one of my favourite ever poems.

EM: Thank you. I wrote it in Chicago. I really feel like I fell in love with the city. I feel more in love with myself when I’m there. More bountiful. And I think that’s very much true of the city.

ROOM: That’s beautiful. Is Chicago the city you are writing to in “How do you write a love letter to a city you don’t know how to love?” Or is that Toronto?

EM: That’s Toronto. Yeah, and that title, someone just said that in a conversation, because there are just poets out here running amok! I was processing this line as well as a situation, then came up with a list of these little offerings. Maybe there’s a way that some things can be enjoyed without being tainted.

By all hands you are a kind weaver

Universe, could you share the trick of unravelling?

(“Universe,” Elizabeth Mudenyo)

ROOM: Can you talk to us about what this poem means to you?

EM: Well, I think about God and the universe synonymously. And when I think about prayer, I just feel that I’ve been really blessed but there are a lot of people in my direct proximity like my family and friends, that could use a blessing. Even in really small ways. Like, you don’t have to give them receptors for joy if they don’t have them. I’m not asking you to turn the world over. But if you could just give these people little things, I think that could make a world of difference.

Another theme in my work is cycles that are hard to break. There are a lot of things that are cyclical, and have been fixed for a long time. So that last line is also about how do you break or dismantle things? And create openings for other things to come in, like beauty.

ROOM: What’s next as a writer?

EM: It’s nice that there are a lot of people getting to know me better through this book. I want to do a collection titled ( ) (“bracket space bracket”). Particularly about the framing of this time. Part of me wants the pandemic to be its own singular thing, even though I don’t think it will be. I want to release a collection that spans from April 2020, to April 2021 to encapsulate that. Another EP, all hits, no fillers haha.

I’m also working on a larger collection that’s about Black mental health and my family, but there’s no rush for that to be done. And then I’m really interested in curation and exhibition. The things that make writing exciting or interesting are not unique to writers. There’s a way to open up that conversation to everyone, and talk about meaning making and language in a public forum. So, yeah, that would be the hope at some point, to do a public workshopping event.

ROOM: If you could, please share with us the title of a poem that you love.

EM: “You Are Who I Love,” by Aracelis Girmay. She does a lot of long form poetry and writes from an extremely tender place. She’ll look at a gesture, how it connects to her, then how it ripples into the world. And I wish I was filled with that much language and magic and love. She’s definitely pouring with love, even when she’s talking about really difficult things.