[Interview took place on Wednesday September 22, 2021 via zoom and has been edited for brevity]

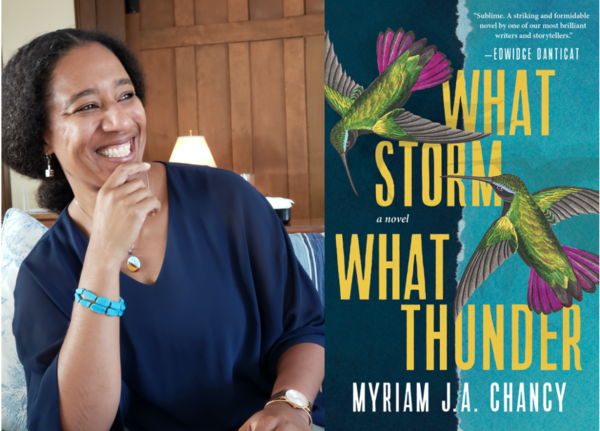

Myriam J.A. Chancy’s latest work, What Storm, What Thunder chronicles the lives and perspectives of ten characters in the aftermath of the 2010 earthquake in Haiti. Her brilliant storytelling, lyrical prose and focus on Caribbean women has been praised widely by Edwidge Dandicat and many others. We spoke on September 22nd, and our conversation on What Storm, What Thunder took us to the markets of Port-Au-Prince, discussions of spirits, gods and queerness, encounters with Trinidadian painter LeRoy Clarke, Haiti today and it’s essential role in the Caribbean.

ROOM: Welcome Myriam. I want to thank you for your incredible work highlighting the lives and histories of women in the Caribbean, in your academic writing but also in your newest novel What Storm, What Thunder.

MYRIAM J. A. CHANCY: Thank you for inviting me to this conversation—Yes, in this novel, I wanted to achieve a balance in terms of representing gender and sexuality, but also have the weight fall on the side of the women. Haiti is still a very patriarchal society yet, it is really upheld by the toil of women, and so I wanted to have those voices be the ones who held the text together. For instance, the voice of Ma Lou, the market woman, opens and closes the novel. The market women have become a kind of easy symbol for Haiti that’s used when there are catastrophes to show the endurance and ‘resilience’ of Haitian people—but the women’s interior lives themselves are not examined. They’re never actually spoken to, or asked how they see the future—their futures, and the future of Haiti. After 2010, during reconstruction, a question I asked was who should we talk to? It’s the market women who hold everyone together, and who understand the global economic issues very intimately—much to many peoples’ surprise.

ROOM: One of my favourite lines is from Ma Lou. She says,“The saints, the crooks, the foreigners, the white saviors, the bleeding hearts, they all need sustenance, and we give it to them.” Wooo! There are so many hands in Haiti looking to profit—and Ma Lou witnesses everything.

MJAC: Women in the marketplace are treated like they’re just objects. But, yes, they hear everything and see everything, so they know before anybody else knows what’s actually going to happen. Politicians talk in front of them, everybody talks, and so they really have a deep insight. My maternal great grandmother was a market woman. So I also wanted to bear witness to her life. Even within my own family, it’s often forgotten how much she contributed to the future success of her family. She started with a stall on the street, and then built up a business and ended up with a covered market in the Marché de Fer in Port-au-Prince, which was destroyed in 2010, and later rebuilt.

ROOM: The lives you show have very disparate experiences of the earthquake. Why was it important to you to tell What Storm, What Thunder, from ten different points of view?

MJAC: Originally, when I was working through the manuscript, I had 12 voices, and it was to echo the date itself of January 12, 2010 (people have a number of different names for the earthquake, but Douz is one of them); two were cut in the revision process to keep the narrative tight. Still, I stuck with a plurality of voices to counteract the “massification” of a devastated people. When there’s devastation, there is this sense in which we’re told that we can grasp what people went through by just talking about masses. Because this is also my personal experience as someone who is Haitian, I spoke to people within my family groups and professionally, who either experienced the earthquake directly, or were working on issues related to the earthquake aftermath and what I witnessed were a lot of very, very different experiences of how to process the earthquake. None of them were worse or better than the other, they just were. I wanted to reflect this reality through the ten voices of the novel.

ROOM: Your stories float between the market, camps, the underside of houses, survivors and ghosts, to the top of the mountain—and a hidden world of decadence, where the wealthy mock and have contempt for the poor of Haiti—there are many lines of class, mobility and colorism drawn through these characters. What is your process to get into all those points of view?

MJAC: In the past, I thought about structure first, and then found my way into the characters. This particular novel was a little different from my previous ones. Before I began this novel, I had an encounter with a Trinidadian painter that shocked me into realizing I needed to write it. I was not planning to write What Storm, What Thunder—I was actually refusing to write the novel. I had wound down my post-earthquake work. I was in Trinidad and a friend of mine said you really need to meet this painter, LeRoy Clarke, who unfortunately just passed away in July, and so he hasn’t seen the novel; that was going to be a gift—But at the time, he was painting a cycle on Haiti. He had started the first painting in 1986, at the end of the Duvalier regime, and he had never finished the painting. He had started, and then he just stopped. The earthquake happens, and he starts painting furiously. When I went to visit him in 2013, he had 77 paintings of what ended up being an 111 painting cycle of different sizes. At this time, LeRoy had never been to Haiti. Never met a Haitian painter. But when I saw the paintings, I just started weeping, and when he came into the room, he asked me, “What do they mean?” So I started explaining to him what I saw. It’s hard to explain. When I went home from that trip, I started thinking, “Well, what does it mean to have had this encounter, to have looked at those paintings, to translate the visual into words for the painter who is painting them?” And as soon as I started asking myself the question: what’s the message here? All the characters came. I wrote an outline. And it wasn’t a structural outline, it was there is this little boy, there is this market woman, there is this mother with a little boy, there is her husband—all the voices started to come. The finer details which result in the novel occurred over many years. With some characters, I didn’t know if they were dead or alive, for instance. I had to figure that out while I was writing. So for Jonas, the little boy, I had an intuition right away that he had not survived. And he was the first voice that came to me. But he’s still alive, and that’s why his voice is written the way it is, which reflects a very deep Vodou belief—that the dead don’t leave.

ROOM: Throughout the Caribbean, there isn’t a separation between the everyday and the fantastic, the living and the spirit. Could you speak to the role of spirits and the dead in the work?

MJAC: Sure. One of the epigraphs at the beginning of the novel is an invocation to the Loas. Ma Lou’s section also begins with an incantation to one of the manifestations of Erzulie. I wanted the reader to feel right away that they were being brought into a place where spirituality animates the culture in the best of ways—to accompany the characters in their lives. I also wanted to signal to readers an understanding of a world beyond the material. Sonia and Dieudonné [both queer characters] are deeply steeped in a knowledge of a world you cannot see, which is why Dieudonné has intuited since the very morning on that day, that there is something wrong. Both he and Sonia have visions—of Baron Samedi, the god of death, a man who is staring at Sonia, making a rhythmic noise with his cane on the morning of Douz. I wanted to infuse the work with this sensibility of Vodou culture. I wanted to be very explicit about the importance of Vodou in Haitian society, and the importance of the dead within Vodou society, in terms of ancestors and the greater pantheon of gods, but also to reflect how individuals can become gods. I think [non-Haitian] people are knowledgeable about revolutionary leaders, like Dessalines, like L’Ouverture, being considered Loa, but sometimes are less aware of the possibility that an individual, a family member, can also become part of that realm. Perhaps what compelled me to show more of this, was the discourse around Haiti being somehow doomed. I wanted to interrupt this notion. I chose to show that interruption most explicitly in the figure of Sonia, because both with this earthquake and another that took place in the late 1800s, in Cap-Haïtien, lesbians, as a class, were blamed. Consequently, I wanted to have a queer figure—in Haitian society, we use the term M, M society, which cover different terms that begin with “M” (madivinez, masisi, makome) to define a variety of queer identities. Both Sonia and Dieudonné talk about being part of M society. This is also why Sonia has a very particular role in the healing process, at the end of the novel, which is also related to Vodou and a sacred Vodou site in Haiti.

ROOM: It is a fascinating clash that queerness has an important role in spirituality, but that a natural disaster might also be blamed on the M community.

MJAC: Yes, I haven’t been able to find much information as to why that is, why this happened. I do know that a Haitian feminist within Haiti will often be cast out—in the middle to upper class sectors of the society—and labeled lesbian as a way to negate their various activities (this form of discrediting of feminism by associating feminism with queerness also occurred in other parts of the world throughout the late nineteenth century to mid twentieth century and persists in various ways). The figure of the woman who has a non-heteronormative sexuality becomes very threatening in a society defining its structures of power through patriarchal models. So, when something cataclysmic like an earthquake occurs, I think that powerful feminine and feminized symbols – this woman who has been deemed a non-woman for her lack of heteronormativity, who has gone out of bounds, becomes an easy target. Which is why in other parts of the novel I exploited that image, of Haiti as a woman “out of bounds.” I was trying to think of the landscape as having, perhaps not control, but some kind of agency. I also wanted to invest the figure of the market woman with a different kind of power—a voice, whether it’s a natural voice, or the ocean coming together with the landscape, as with a lover, or a literal one, like Ma Lou telling her version of what she saw and what she lived through.

ROOM: What Storm, What Thunder was released a handful of weeks after the August 14th 2021 earthquake in Haiti. Which was followed on August 16th by Tropical Storm Grace. How do you process that, and how do you hope readers process it while reading What Storm, What Thunder?

MJAC: I’m still processing myself, and I have a couple of things I’m working through—there is also the issue of the 14,000 Haitian migrants who made their way from Chile and Brazil to the Mexico/US border on the false information that the US was offering asylum and faced massive deportations (in the age of Covid-19) by the Biden administration which utilised a Trump era law, Title 42, which allows the US to deport refugees without due process to protect the health of US citizens. The fact is, though, that these deportations are also related to a 2001 ordinance under Bush which designated Haitian refugees as national security risks. The fall 2021 migration of Haitians through Lain America to the US is not directly related to people coming out of Haiti because of the recent earthquake or the tropical storm, but may be related to conditions post 2010 when both Chile and Brazil opened its borders to earthquake refugees but closed them a few years later. Haitian refugees in these countries were faced with racism, xenophobia, and loss of opportunities. These adverse conditions were exacerbated with the onset of Covid-19 when many countries in Latin America suffered severe economic setbacks to say nothing of loss of life due to the pandemic – loss of life and loss of livelihoods. But, to speak directly to your question and the connection between these events: I was talking to people who survived the most recent earthquake, August 2021 earthquake, some whose family members did not survive, about the trauma of 2010. They report that there is a resurgence of everything that people went through in 2010, and have still not healed from. What happened on August 14th, 2021 (August 14th, incidentally, given that we were talking about Vodou spirituality earlier is the anniversary of the Bois Caiman gathering, a Vodou gathering in the late 1700s that set off the Haitian Revolution) brought out so much unresolved pain. I’ve been fielding some requests for mental health assistance, and finding out thankfully, that there are people who have developed specialties, counselors—some are young people who’ve gotten degrees in these areas to deal with the post 2010 trauma, and now the new traumas that are adding on to that. Initially, I was really saddened by the events of this past summer—it took me a long time to write this novel, maybe five years, and then more for the revisions after the novel was placed. I kept feeling like the novel would come out too late. Partly, I wrote it because, as the years went on, with every anniversary, fewer and fewer non-Haitians were remembering what had happened. There was a kind of leaving behind of Haiti. All the NGOs that had been working there just started leaving. Things got worse economically, in terms of security, all the things that we now know more about after the July 7th assassination of the Haitian president. There was a kind of melancholy, a bittersweetness about it all—I’m happy the novel is coming out, but I would have wanted it to be more of a historical note but it seems to be bearing witness to what people are going through now. I write historical fiction. This is the first work that I’ve written where the history is so close to us. 2010 is not so long ago.

I think what I’m hoping that the novel can do is to sensitize readers who may not be aware of what happened in 2010, the extent and depth of it, because I’ve had a lot of people who have read the novel tell me that they didn’t recall the earthquake; they knew something had happened, but they didn’t recall what had happened. They didn’t recall the scale. As things continue to occur right now, to Haiti and to Haitians, perhaps it can make people more aware of how to respond more adequately.

ROOM: Yea, certainly. I’ve been thinking about the Haitian community at the border to Texas but also Canada’s own failings supporting people who are migrating. As we see all of this pressure building, whether political pressure or natural disasters, there are many calls for Canada to abolish immigration detention and develop a policy around climate refugees. What do you think is the role and power of literature to influence public opinion and policy on issues such as immigration?

MJAC: I think it can do a lot. It’s been interesting during this pandemic to see how much people are reading. I think that there’s enormous good that can be done. I’m also an English professor so, clearly, I believe that the teaching of literature can be sensitized and I’ve seen its effects on my students over the years. I’ve seen literature change people’s minds about things they thought they knew, because often people will read things thinking, Oh, I know all about it. So literature exists not just to change the minds of people who have no awareness, it’s also sometimes corrective for people who think they already know, and that they don’t need to know more. Of course, I’m not claiming that fiction can take the place of historical texts or of memoir or of nonfiction. But I do think it can play a role in jumpstarting the imagination of the reader to be more flexible about how they approach the world. I think the role of fiction in particular is to humanize. With climate change and the pandemic, we are experiencing similar kinds of duress, and those of us who are not experiencing duress to the same extreme as others around the world should think about why.

ROOM: Who are your writers Myriam? The ones you love, the books that you read over and over again, the ones you keep within arms reach?

MJAC: James Baldwin is probably the person I go back to the most. I read him first as a teenager and also teach a Baldwin seminar. Back then (as a teenager, in Winnipeg), Alice Walker’s In search of My Mother’s Gardens led me to Countee Cullen and to Langston Hughes, and certainly [Zora Neale] Hurston is somebody I go back to. I recently wrote about the Kreyol influences in Their Eyes Were Watching God—there is actually a lot of Haitian Kreyol that’s transmuted into Black English in that novel, as well as some other Haitian concepts and historical moments related to politics and gender. I wrote a chapter on her [and Claude McKay] in my last academic book, Autochthonomies, which is all about how people of African descent talk to one another across geographical difference and time.

ROOM: I’d love to read your work on that.

MJAC: Thanks- please do! Somebody like [Margaret] Atwood has also had an influence. I like her mode of storytelling. This will sound funny but I delight in her use of punctuation—I have always been amazed by how she uses the double colon, for instance. Raymond Carver was another influence. He’s what people call the father of “dirty realism.” I had an epistolary exchange with him when I was 16. They used to publish writers’ addresses in newspapers and magazines back then [in the mid-1980s] and I was like, I’m going to write to him, and I got an answer, written to me in his voice but via his partner, poet Tess Gallagher! They gave me three pieces of advice: read poetry, revise, revise, revise, and don’t smoke. He died of lung cancer three months later.

A Small Place by [Jamaica] Kincaid, I go back to a lot. Just recently, my favorite book of 2021 was Cherie Jones’ How the One-Armed Sister Sweeps Her House. This was her debut novel and it’s just stylistically flawless.

Of contemporary Haitian women writers, I love Emmelie Prophète who writes in French but has a book, Blue, coming out in 2022 in English translation. The first work I read by her (and then decided I will read anything she writes from here on) is called Impasse Dignité, which translates to ‘a street named dignity.’ It’s about all the people who live on a particular street in Haiti and their relationship to each other; they also have a relationship to the 2010 earthquake which you discover at the novel’s end. As you read it, you realize she’s getting to a point about dignity for Haitian people because “impasse” in French also means “dead end.”

ROOM: The commissioned piece we are hoping to publish in issue 45.2 is from the point of view of Loko, the rainwater man who appears in What Storm, What Thunder—and a deeper dive into his character. We’re very excited. Is there anything else you would like our readers to know about you?

MJAC: I’m really pleased to have been asked for this interview and that you’re in the process of making more Caribbean writers visible, especially in Canada. I know from the launch of the Canadian edition of What Storm, What Thunder, that it feels like there’s still some resistance to Caribbean Canadian voices, as if there would be no interest in what we bring to the literary or cultural table. This has been surprising to me, not only because I grew up in Canada, but also because there’s such a notable Haitian-Canadian population. Maybe it’s to do with language? I’m twice displaced from Haiti, being raised in Canada, and then coming to the US in my early twenties, and I write in English, which is considered atypical for a Haitian writer.

As a scholar, I started out by exploring the work of Afro-Anglophone women Caribbean writers, and connected them to Haitian women writers—with the work of Marie Chauvet, in particular. From there, I went on to write the first book in English demonstrating the cohesiveness of a Haitian’s women’s literary tradition and then, in later work, connected Haitian American women’s writing to that of Cuban American and Dominican American women writers to show the connections between the three traditions. Both in my scholarly and creative work, I am continuously redrawing the map of the Caribbean, and of North America, to say Haiti is a part of this whole.