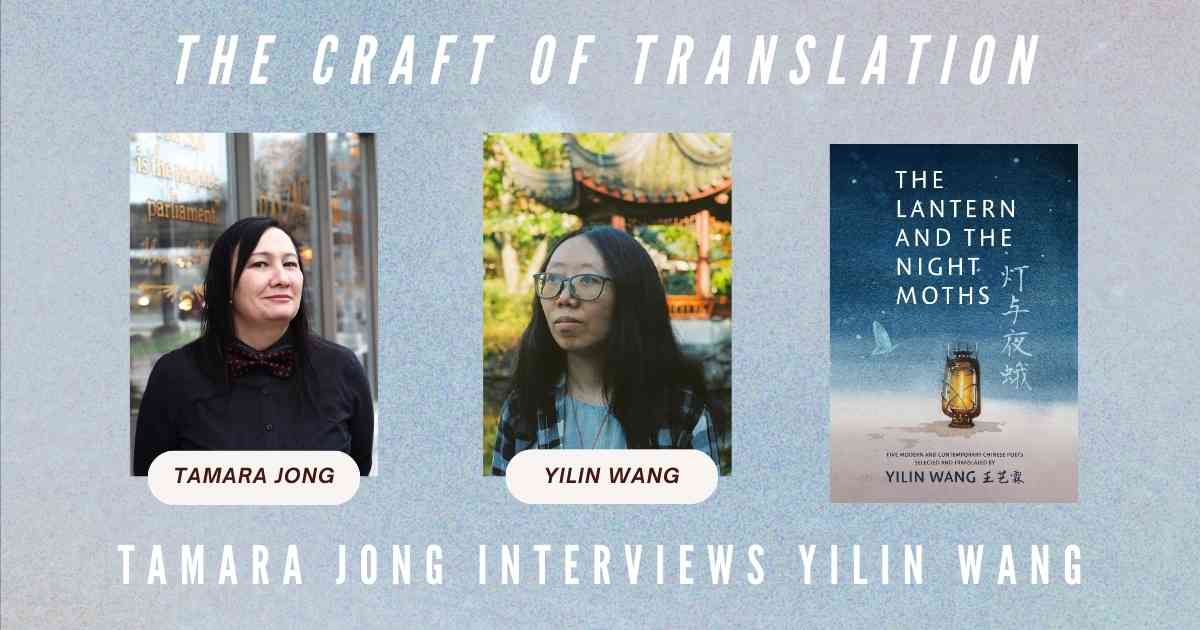

What is the relationship between translation and resistance? In this interview, former member of Room’s collective, Tamara Jong, speaks to author Yilin Wang about translating poetry, celebrating meaning, and more.

Yilin Wang 王艺霖 is a writer, poet, editor and Chinese-English translator. Their debut book, The Lantern and The Night Moths, which CBC called a “poetry collection to watch out for,” and Open Book referred to as a “crucial anthology of Sinophone poetry,” introduces us to five modern and contemporary Chinese poets, Qiu Jin 秋瑾, Zhang Qiaohui 张巧慧, Fei Ming 废名, Xiao Xi 小西, and Dai Wangshu 戴望舒.

This carefully curated collection of poetry translated by Wang is accompanied by rich personal essays that are in conversation with the deep connection the poet-translator has with each of the chosen poets. In this compilation, Wang balances the complex task of excavating the meaning and bridging the spaces between not just language and interpretation but the purest attempt to capture what each poet means to convey in the spirit that it was written.

The amount of research and work that goes into the work of a poet/translator is no small task. Wang wrote in “Faded Poems and Intimate Connections: Ten Fragments on Writing and Translation” that “For me, the acts of writing and translating poetry are also acts of salvaging, a form of quiet resistance,” and the process as, “this long path of recentering and reclaiming.” Wang’s own lyrical poetry examines several themes of hauntings, loneliness, spirits, longing for home and belonging, and there are similar threads and lines that stood out within each of the particular poet’s body of work.

It’s not surprising that this collection just recently won the Canadian John Glassco Translation Prize for being the best debut book of translations into English or French by a Canadian translator published this year.It is the first time the prize has gone to a translator who has translated from Chinese or any Asian language in the 40 year history of the prize.

When reading Wang’s words to Qiu Jin in “Dear Qiu Jin: “To Meet a Kindred Spirit Who Cherishes the Same Songs,”—as I read and savour the melody of your words, I wait alone in this room for your voice to rise from among the pages, slowly, to cross time and distance, until it’s as if we’re sitting side by side, meeting for the first time chatting spiritedly late into the night”—it struck me that Wang’s translations have brought these poets back to us in splendor with this exquisite anthology and it’s a marvel, and experiencing the gift of having these essays at the end of each poets’ section adds an element of richness that celebrates their work, lives and Wang’s relationship to these five poets.

TJ: Your dedication in your book goes to your wàigōng and wàipó and their love of poetry, storytelling and the written word. Would you mind sharing your earliest recollections of the stories and poems they shared with you?

Yilin Wang: When I was very young, I spent a few years living with my wàigōng and wàipó (maternal grandpa and grandma). My grandma was the one who taught me how to read and write in Chinese again after I forgot the language due to a few years of living abroad. My grandpa used to tell me many Chinese folktales, like excerpts from the Romance of the Three Kingdoms 三国演义 and Journey to the West 西游记, as well as shared poetry by writers such as Li Bai and Du Fu. Our conversations really inspired my love of Chinese literature, and without that, I would not be the writer and translator I am today.

TJ: In thumbing through my now very well-worn beloved copy, which has been read through at the very least fifteen to twenty times now, I kept coming out with something new every read-through. A line, a meaning, an image… I’ve outlined and scribbled notes throughout my copy.

Your book feels like a master class in translation, a primer for those who want to be introduced to the rich work of Chinese poets. Possibly for the very first time. What’s interesting is that usually, in a book of poetry, we don’t get to have a one-on-one with the poet translating why they chose this word and not that one, but we get to enjoy this via the essays that follow the end of each selection. Can you please share with us how you selected these five poets, how you organized their work, and the order you chose?

Thank you so much for your careful reading and kind words. I definitely envisioned the book as being potentially helpful to other literary translators and people interested in the art and craft of translation, in addition to those who have a fondness for or interest in Chinese poetry. I wanted to create an anthology featuring 5 modern and contemporary poets whose works resonate with me, and whose work would give a wonderful overview of the myriad of voices out there. In particular, I considered poets whose work might be of interest to a Sino diaspora readership. The poets in the book touch on a range of subject matter, ranging from longing, gender, and feminism to Buddhist and Daoist philosophies to one’s relationships with home, ancestral lands, and heritage languages. I read through each poet’s collection(s) and body of work, and picked 5-6 poems that are representative. I then started with Qiu Jin’s poetry, because I felt that the themes of longing and connection in her work run through the anthology and my essays. I then alternated between modern and contemporary poets.

TJ: I did feel that when thinking about some of the parallels between your own writing and that of Qiu Jin’s and then when I read the line, “In the crimson-dust world, where can I find my kindred spirit?,” that she may have found one through these thoughtful translations. So, it’s only fitting then, that in your opening choice of poet, we are introduced to Qiu Jin (1875-1907), a poet, feminist, revolutionary and martyr. A poet who defied the conventions of their time within their writing and challenged the gender norms and roles that were expected at that time in society. Qiu Jin defiantly writes in “A Reply to Ishii-kun in Matching Rhyme,” “Don’t speak so easily of how women can’t become heroes —/ alone, I rode the winds eastward, for ten thousand miles.” Qiu Jin quickly becomes a fan favourite for me just for this line alone.

In their poem, “Púsāmán: To a Female Friend,” in the style referred to as cípái 词牌 (poetic form), Qiu skillfully uses motifs of the moon, the mountain, the currents, heartless, cold gusts of wind and asks, “When will we finally reunite as we yearn to?” speaking of “the melancholy of longing, here and elsewhere.” What’s noticeable about this poem and the others selected is the loneliness that is felt in the lines when speaking of their search for their kindred spirit, a zhīyīn. What must it have been like for a trailblazer like Qiu Jin then?

I think it’s very hard for women and femmes now to understand all the gender norms, expectations, and biases that Qiu Jin must have dealt with, as a young woman living in the final years of the Qing dynasty. Married to a husband whose values and interests differed greatly from hers, she must have felt very isolated and frustrated, which no doubt contributed to her decision to eventually leave and go study abroad. When I was reading through her body of work, I came across many poems that delve into her struggle with gender expectations, the flourishing of her feminist ideals, and her longing for a zhīyīn.

TJ: In your essay about Qiu Jin, you wrote that you became familiar with their work because a friend recommended them and that you wanted to push back against the erasure of feminist writers in Sinophone and Anglophone publishing,” and in an interview with Hypertext Mag, you pointed out that, “many Chinese poets have long been and continue to be translated by white sinologists, some of whom have created very poor translations with problematic representation.” I was stunned to read of bridge translations (in conversation with you) where the translator doesn’t even speak the language but simply translates word for word, working with a native speaker. I had no idea! I always assumed the translator knew the language! Can you please talk about this practice and how you challenge this idea?

Bridge translation is a practice that often happens to poetry translated from Asian languages. It is where a writer (often white) who can’t read the source text is handed “literal translations” or “word by word definitions” of a poem, from which they would craft a poem and call a translation.

I feel that the practice arises from a very misguided belief that to be a translator, you do not need to have any other skills beyond the ability to write well in English: you do not have to have bilingual knowledge, familiarity with the syntactical and linguistic features of the source, the work’s literary traditions and context, close reading skills, and the ability to conduct independent research. The practice is also rooted in the mistaken view that being an excellent poet in English would automatically make one a better translator, even more so than literary translators who very may well be equally skilled writers in one or both of the languages that they work with.

What irks me is that this practice is sometimes encouraged by certain writing and translation workshops, where organizers like to encourage writers to “try translating” even without knowing the source language. There is no consideration for what is being translated, whose work it is, the lived experiences informing the work, the context in which it was written, the power dynamics between the source and target languages.

The works created through bridge translations may be very well-written works in English, but in my opinion, they represent more of a fantasy of what the poet imagine about Chinese poetry rather than what’s actually on the page.

In response to this, I think it’s very important to highlight the role of literary translators in the creation of translated works. It’s crucial to have more conversations about the ethics of translation, the choices being made by a translator when reading, interpreting, or translating, and who shapes what texts are translated or overlooked. I delve into these ideas in my essays that accompany my translations.

TJ: I was wondering how words, meanings and context change over time, and are continuously moving forward. How does this affect the translation and how do you as a translator navigate this?

You raise a very good point here about the changing, non-homogenous nature of language. When I’m translating poetry, I’m not only working with just the source language, but also the specific stylistic and linguistic choices being made by each poet, their particular way of writing in Chinese. This is most notable when I am translating poetry by Qiu Jin, who lived more than a century ago, and wrote in Classical Chinese, a language distinct from modern Mandarin. This means that many of the ideographs in her poems, while recognizable to modern speakers, do not hold the same meaning and connotations as they do in modern Mandarin. I have to be very careful to draw on my knowledge of Classical Chinese, extensive annotations, and contextual research when translating her work. It’s very important to pay attention to diction choices and to consider the literary, cultural, historical, and sociopolitical context for a poet’s work when translating.

TJ: I could feel the connection between the space of translation of poet and poet within Qiu Jin’s work. It made me want to learn more about this fearless poet. For those interested about Qiu Jin’s life, what resources did you enjoy digging into or getting lost in?

A starting point would be this New York Times article about Qiu Jin. If folks want to learn more about her life and work, I recommend the documentary Autumn Gem, which is available in Mandarin and English. I also really enjoyed watching the Chinese bio-pic Qiu Jin (1983), which unfortunately does not have English subtitles, but would be very informative to those who can understand Mandarin. For an in-depth dive into the story of Qiu Jin’s death, many burials, legacy, and her friendship with her sworn sisters, I recommend reading Hu Ying’s monograph Burying Autumn.

TJ: In your essay, “On Xiao Xi: The Infinite Possibilities of Poetry Translation,” you write, “But not every word has a perfect equivalent in another language, even if you sift through all the possibilities.” In particular, you referred to 注意,where you chose to translate it as, “pay attention to.” I returned to the text and tried to find the ten times it was repeated within the poem. I read aloud in English to see how it sounded and appreciated how you chose to deliberately and slowly reveal to the reader how they may appreciate what is around them but not noticed initially, perhaps taken for granted or missed altogether, like tiny blades of grass, light reflected on broken glass, to see farther than the surface would show us and the slow revealing of sorrow. It’s really an art to disassemble and build something up again in a way that will convey the meaning the poet wishes to articulate. How long does it take to do the research and care to convey and uncover the meaning of the work that you’re translating? How do you translate and interpret for that unknown reader?

Yes, that was one of the first poems I translated for this anthology, and translating it made me think a lot about word choice, and what to do when there is no exact match. My translation process is quite slow. It’s common for me to go through anywhere from between 5 to a dozen or more drafts. I start with making annotations, then create translations that very closely follow the source text, and then make various adjustments, sifting through possible choices, to consider the differences in difference and the emotional experience of reading the poem in English. I rewrite lines repeatedly, sometimes spending hours thinking about a handful of words. When I translated this book, I kept in mind that I want it to reach readers with an interest in poetry, translation, and Chinese literature, who may have some prior knowledge or exposure but does not necessarily read any Chinese. I then made my translation decisions based on these assumptions about my readership, while keeping in mind the reading experience for those who can partially or fully comprehend the source text. A translation is always an interpretation, so there is inevitably a level of subjectivity involved.

TJ: From Zhang Qiaohui’s “Soliloquy,” the line, “Jiàochǎng Hill’s graves have long been displaced, now covered by lush greenery/. In the mortal world, a saying, to be without a resting place even after,” gives one pause. It was surprising to learn that this happened. The graves were physically moved, and the space became a public park. What happened, and what was the relationship between the poet Zhang Qiaohu and this place?

I discuss (an earlier version of) my translation of this poem in my Translator’s Note published in The Common. Zhang Qiaohui writes frequently about the city of Ningbo where she lives, exploring themes of heritage preservation and gentrification. I explain in my note: “When Zhang Qiaohui was still in school, she sometimes sat quietly in the cemetery, letting her thoughts dwell on history, on eras of war and prosperity, and on death.” When I was discussing my translation with Zhang Qiaohui, she talked about going for long walks through the cemetery grounds. It’s lovely that her writing practice is so rooted in movement and in place. Her interest in writing about gentrification, homelands, and ancestors is what draws me to translate her work.

TJ: In reference to “On Fei Ming: To translate Nothing and Everything,” you said that you read the poem “lantern” over fifty times to translate it. Was Fei Ming’s work the most challenging to translate among all the poets? How do you know when it feels like you’ve captured the meaning of what the poet meant to convey?

Yes, I definitely spent the most time revising my translations of Fei Ming’s poetry when working on this anthology. The poem “lantern” was the most difficult one to translate. It was very enlightening (pun intended haha) to learn more about his use of Buddhist references, particularly the tale about Mahākāśyapa smiling at a flower in silent understanding. The story reminded me of something I had forgotten, that poetry is not always meant to be logically unpacked, but rather to be experienced, read, and felt. I think the beauty in Fei Ming’s work is in its elusive style and tone, the way that he leaves so much that is ambiguous and unsaid. I tried my best to preserve that through conveying his ambiguous tone, strings of imagery, and use of silence.

TJ: In your final essay, “On Dai Wangshu: Poetry is What Survives Translation,” it was noted that Dai was also a translator who was influenced by western and classical Chinese poets and that he felt that poetry should be translatable into other languages. You wrote that you want “to share voices often underrepresented in translation,” and you hope to continue Dai’s work. It’s a lot of work, and you’ve been very committed. What inroads do you see happening in the publishing world regarding translation? What would you like to see?

I think there have been more discussions about the importance of reading, supporting, and publishing translated literature (but it could also just be that I am surrounded by literary translators). I always like to draw people’s attention to the Manifesto on Literary Translation for a specific list of calls for action. Personally, I would especially like to see more thought and care put into the editing process for books, especially at the copy-editing stages, where translators of color may encounter micro-aggressions if they’re dealing with an editor who lacks cultural sensitivity and training in anti-oppressive editing practices. I’d love to see more publishers and magazines led by BIPOC that prioritize publishing translators working on the literatures of the Global South and that treat translators as respected partners and collaborators during the editorial, production, and promotional stages.

TJ: What has been the most exciting collaboration you’ve done with The Lantern and The Night Moths?

Earlier this year, a friend of mine connected me with the Tangram music collective co-directed by Alex Ho and Rockey Sun Keting. They were working on a musical about the lives of Afong Moy and Qiu Jin, and their project was inspired in part by my translations of Qiu Jin’s poetry (which were used initially without permission, credit, or pay by the British Museum in a major exhibit last year). Tangram ended up featuring some of my poetry translations in a pamphlet printed out to accompany their performance. I even got a chance to see them rehearse while visiting London. It was really moving to see Qiu Jin’s words take on new life in this way, and I’m excited to pursue more collaborative projects of this kind in the future.

[Note from Tamara: While Yilin was in the midst of writing an early draft of her essay “Dear Qiu Jin: “To Meet a Kindred Spirit Who Cherishes the Same Songs,” she discovered that the British Museum had used her previously published translations of Qiu Jin in their exhibition “China’s Hidden Century” for over a month without her permission, credit, or compensation. After a very public battle where Yilin had to fundraise for legal representation, the British Museum finally apologized to Yilin and credited and compensated her.]

TJ: What are you reading right now, and whose work are you excited about?

I recently re-read Gillian Sze’s book Quiet Night Think because earlier in November, I did a reading with her and her translator while visiting Montreal. Her work was an inspiration for me when I was working on my anthology. Some poetry collections I am excited to check out very soon are: Jane Shi’s Echolalia Echolalia, Zehra Naqvi’s The Knot of My Tongue, Mercedes Eng’s cop city swagger, and Natasha Ramoutar’s Baby Cerberus.

TJ: What’s next for you, and what projects are you working on?

I’m currently at work on my first collection of original poetry written in English. I have also been translating more of Qiu Jin’s poetry, with a focus on the works touching on gender roles, feminism, cross-dressing, and kindred spirits. I hope to eventually compile the poems into a second book of translations.