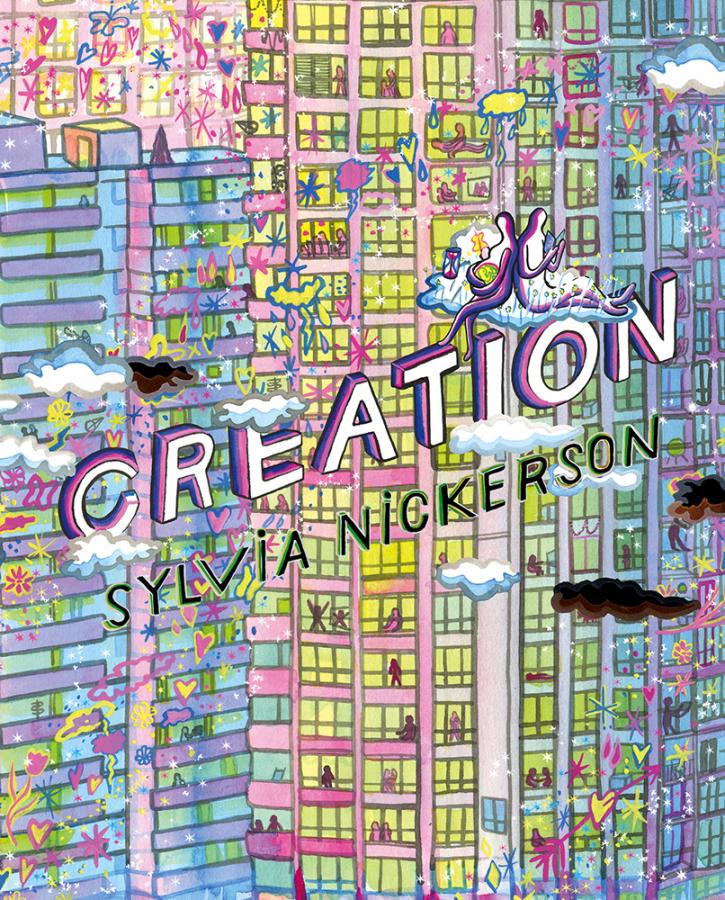

To learn more about her debut publication, Creation (Drawn & Quarterly, 2019), Vancouver-based artist and illustrator, karla monterrosa chats with the Hamilton-based comic artist and writer about her comic, gentrification, the intersection of identity and place, and the roles artists play in a community.

Sylvia Nickerson is a comics artist, writer, and illustrator who lives in Hamilton, Canada. Her focus is storytelling in community arts and writing comics examining parenthood, gender identity, social class, and religion. Her illustrations have appeared in The Globe and Mail, The National Post, The Boston Globe and The Washington Post and her comics have been nominated for a Doug Wright Award.

“Nickerson allows the profoundly personal to be completely universal in her stark, soft drawings and faceless figures. [Creation] is a deeply human, generous book.”—Eleanor Davis, author of The Hard Tomorrow.

To learn more about her debut publication, Creation (Drawn & Quarterly, 2019), Vancouver-based artist and illustrator, karla monterrosa chats with the Hamilton-based comic artist and writer about her comic, gentrification, the intersection of identity and place, and the roles artists play in a community.

ROOM: Creation is such a nuanced piece of work that combines a widely shared experience with a deeply personal narrative. What was the biggest challenge in finding the spaces that intersect personal and public life?

SN: I gave myself permission to write a psychological portrait of a city through the voice of a woman in a time of transition. I decided it was OK to create a highly subjective take on city life linking the intimately personal with common places, events, scenes, and experiences. I wanted to know: How does experience of place intersect with identity? Writing from this point of view was the biggest hurdle. Showing people the result has not always felt like the safe route, but I did try to do the best job I could of the project I set out for myself.

ROOM: It’s clear you’re well informed and have studied the many complexities of gentrification and its effects on cities and family lives. How do you think these conversations are being handled by artists who invest in neighbourhoods?

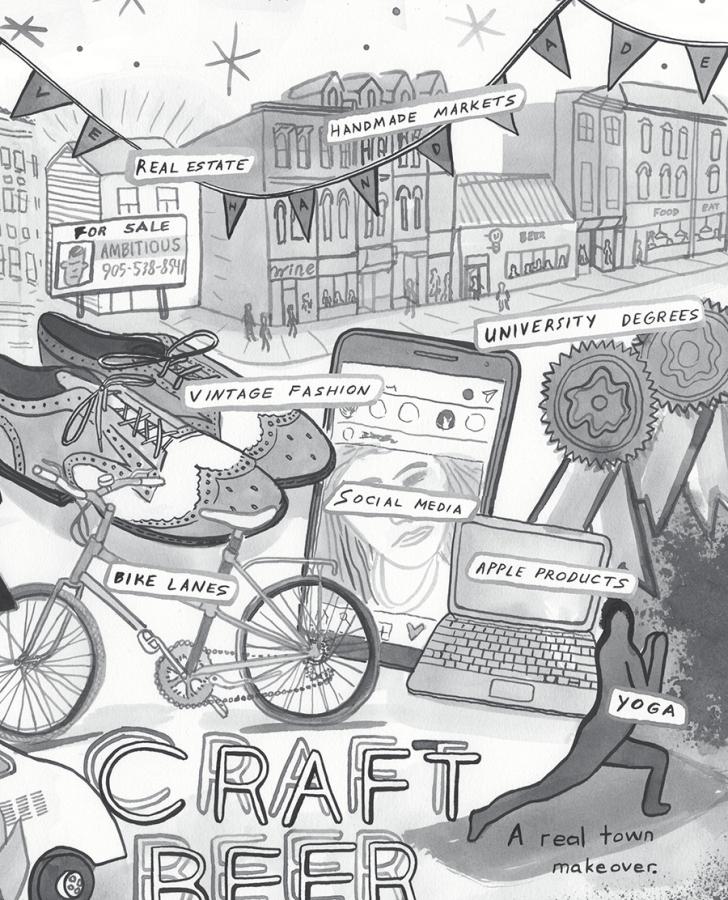

SN: I actually haven’t studied gentrification much. My knowledge is from lived experience. My community in Hamilton is a place where gentrification is being discussed. Some people in the arts resist capitalism and commodification. Some are entrepreneurial and see the opportunity to live cheaply so they can find time for art or music.

Some artists who invest in neighbourhoods do community beautification and boosterism. I wasn’t the only artist invested who did that. Artists paint murals, do community arts, host free events, give to the community in these ways. I think as artists we think we are doing a community service when we beautify or celebrate. This activity projects a more positive or appealing image of the neighbourhood to outsiders. But are our aesthetics racially and socially coded? Is our free labour appropriated by others who stand to profit? Does “beautification” provide cover for sadness and tragedy? I think the conversation in Hamilton on gentrification has moved toward considering a more complex picture of how artists are involved in community life, and that it’s not always good or bad, one way or another.

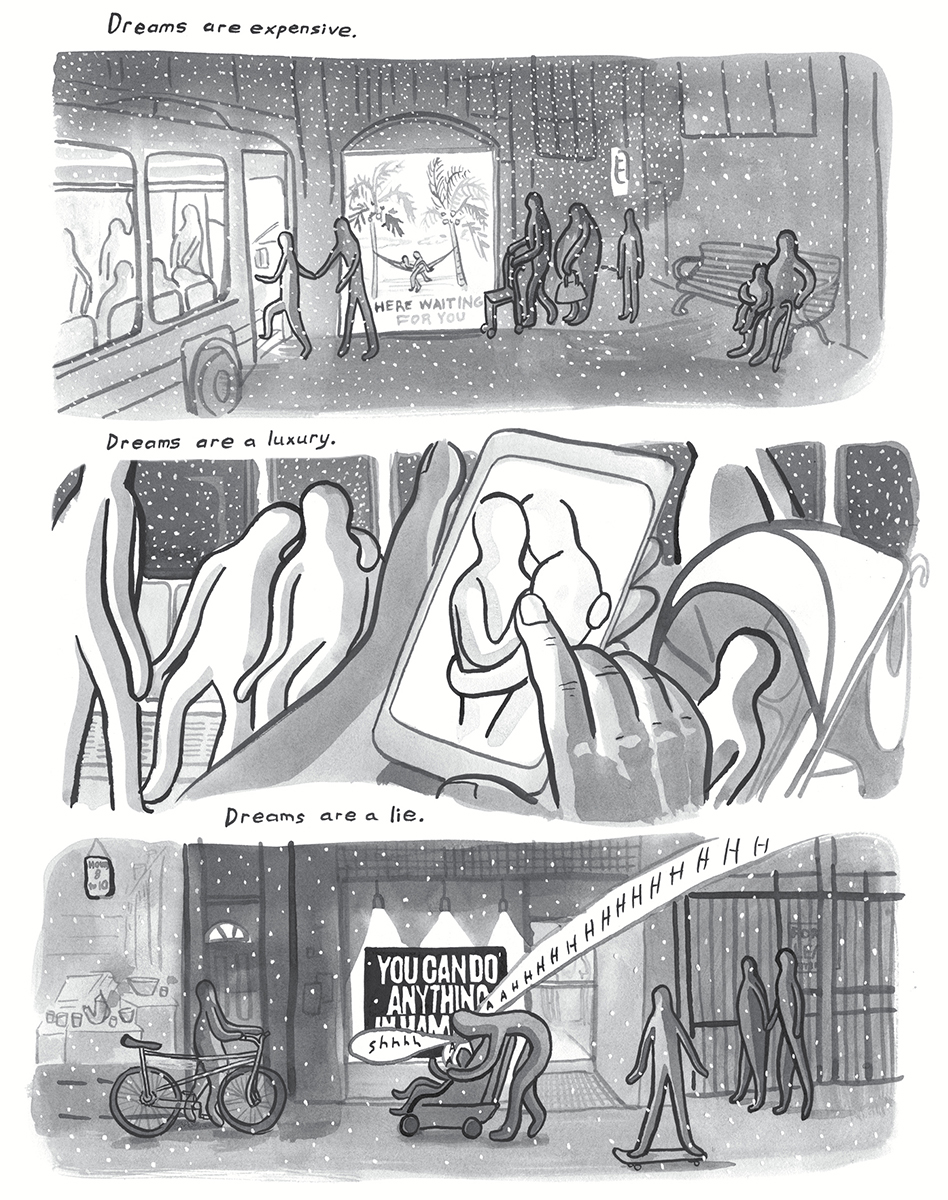

After a decade of being a cheerful gentrifier, I had stored up quite a bit of sadness over many of the failures I perceived to be happening. I was angry at having volunteered for many community development projects while bigger investors profited from flipping properties whose value had increased partly because of these community improvement efforts. I was angry at myself for being hopelessly idealistic in the face of capitalism and marriage. My marriage was disintegrating and so personally I really had to take a hard look at why I came here, what my involvement had been, the state of my dreams, and what it meant to have a family and to be an artist. I can’t tell anymore what the neighbourhood has done to me or what I have done to it. I wrote the book as a way of letting go and coming to terms with what life is now.

ROOM: In Creation, the architecture of the city is portrayed so beautifully; you have done a fantastic work in really showing the many layers of personality so many of these buildings have. However, the people who inhabit the city all look the same and there’s no particular characteristics that make them stand out. Why did you choose to draw people this way?

SN: We pass many people, yet what effect do we allow those people to have on us? I wanted to convey a sense of alienation in the modern urban environment. The formless figures represent people who share urban space but who don’t recognize each other. I mean we do all need to be defended in some ways from the needs and actions of others. But in the story certain characters will at times appear more specifically. In those moments, humans connect and see each other’s humanity.

ROOM: Your work is intimate and strongly political. The conversations about pollution in cities aren’t new, but how do you think they fit into larger conversations about the climate crisis?

SN: In 2012, U.S. Steel turned off the blast furnace in one of Hamilton’s two long-standing steel mills. The brownfield impact in Hamilton is immediately underfoot, and my personal fear lay in what invisible legacies of industrialism had left there, in my garden where I grew food for my children, in the air we breathe. Every generation has their environmental crisis. In my mind it is the legacies of industrialization and nuclear power, because that’s what I know most intimately. That is where my fear dwells most acutely.

The awareness of our environment is something that faces anyone who thinks seriously about the world we bring children into. The climate crisis will be the crisis that preoccupies current and possibly future generations. I suppose I just felt a great sadness that I couldn’t offer my kids a better world than the one I had to offer, which is deeply imperfect.

“Children grow up in the crosshairs of many issues and they have a strong intuitive grasp of that. I think the book itself forces some difficult conversations to happen between us, particularly ones I’d probably rather avoid.”

ROOM: Parenthood and domestic life are strong themes in your book. Do you have conversations with your children about the complex situations their city and neighborhood are in?

SN: Children grow up in the crosshairs of many issues and they have a strong intuitive grasp of that. I think the book itself forces some difficult conversations to happen between us, particularly ones I’d probably rather avoid.

As they get older it will be up to them to decide how to live and negotiate their own relationships to their community and to these larger issues. We don’t always follow the examples set by our parents or find their experiences applicable to our lives because the major issues in society can vary so much from generation to generation.

ROOM: I have lived in Vancouver for ten years and the city has changed so much in that amount of time. The city has become extremely unaffordable for many families and the housing crisis seems to be really out of control. Do you think the arts and artists have a specific role in stopping or changing the policies that allow this to happen?

SN: I don’t think artists have a specific role. As people I suppose we have a conscience, and a certain sense of morality, and perhaps a duty politically. But as a human, I am aware that we are all selfish, fearful, and greedy. My portrayal of life in the book was a look at not just doing good but on failure to do any good at all.

If anything, the arts can bring an understanding of these human complexities. Politicians and lawmakers could probably do a lot in terms of taming the housing market if they wanted to. I see policy as their job, whereas reflecting the human condition adequately is what I can do as an artist.

ROOM: If you could make the most optimistic prediction about the future of Hamilton, what would it be?

SN: In 2018 I connected with a group of women who survived homelessness and precarious housing, and we collaborated on a community mural to help the public understand routes into and out of homelessness for women specifically.

There are far fewer supports for precariously housed women than for men, and shelters for women revolve around serving women with children or women who suffer domestic abuse. That leaves out a lot of other women who are older, widows, grandmothers, women who are single or childless, or whose children are not in their care. Homeless shelters in Hamilton are sex segregated, posing difficulties for trans women or non-cis folks.

In my most optimistic version of Hamilton, all people who pass through my neighbourhood looking for a place to belong would find that place. Women would be safely and affordably housed, and we could all live our lives without fear, victimization or stigma.