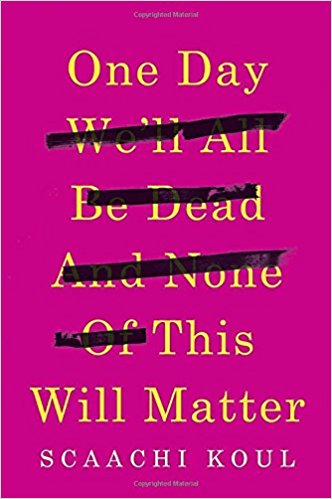

Covering everything from the state of Canadian media to adult summer camps to racist marketing in the beauty industry, Koul’s writing is as thoughtful as it is funny. Her first book, One Day We’ll All Be Dead and None of This Will Matter (Doubleday, 2017), is a sharp and poignant essay collection that covers family, friendship, racism, immigration, rape culture, and online harassment. In the following interview, Koul speaks to Room about writing her first book, keeping family secrets, and why representation matters.

Scaachi Koul is a Canadian journalist who currently works as a culture writer at BuzzFeed. Covering everything from the state of Canadian media to adult summer camps to racist marketing in the beauty industry, Koul’s writing is as thoughtful as it is funny. Her outspoken online presence has earned her an impressive Twitter following and a reputation as an incisive cultural commentator. Koul’s first book, One Day We’ll All Be Dead and None of This Will Matter (Doubleday, 2017), is a sharp and poignant essay collection that covers family, friendship, racism, immigration, rape culture, and online harassment. Her writing has also appeared in The Guardian, The New Yorker, The New York Times, The Huffington Post, Flare, and The Walrus.

Koul grew up in Calgary and studied journalism at Ryerson University in Toronto, where she still lives. In the following interview, Koul speaks to Room about writing her first book, keeping family secrets, and why representation matters.

ROOM: Walk me through your process of writing essays.

SK: I think about something that makes me mad, and then I write about it. I’m not a very organized writer. I don’t create outlines. I think when we were starting the book—I always say “we” because my editors were extremely elemental in the development of it—the proposal was completely different from what ended up being the book. I don’t know if that’s common. But I was so happy with the way it turned out. I think my initial idea was more slight than what the book ended up being.

We knew there were themes we wanted to hit. And thinking about those themes, I knew of anecdotes that could help tease [the themes] out. It came together quite organically. Although, at the time, I remember feeling great panic that I would not be able to fill this word requirement. They give you a contract that says 60,000 words, and you’re like, “How? I don’t understand.” And then two years go by and then, “Ooh, alright.”

ROOM: You have a lot to say.

SK: Turns out!

ROOM: What I loved about your book is that it was so cohesive—even while discussing different topics you explored the same aspects in different ways.

SK: Thanks! I’m glad that worked.

ROOM: I’m wondering how you wove this coherent narrative together.

SK: Some of [the essays] required a lot of work. The last essay in the collection [“Anyway”] was the last thing I had written for my book. And that’s the one about my dad and the silent treatment.

I wrote in pieces. I would write an essay, and I would give it [to the editors], and at the end we read all of them and made sure it felt like there was a thread going through. So, it was a lot of fine-tuning and reminding you about people you read about two essays ago. And the book is basically chronological, which helps.

But, again, that’s the work of a really good editor. I was extremely concerned about it being repetitive. And I was worried about it being disparate. So, I was trying to walk this line of, I don’t want you to feel like you’re reading the same thing over again, but if you’re just reading a block of essays that have nothing to do with each other . . . And there were lots of essays we killed. I had lots of ideas, where I was like, “What about this?” And they said, “Why?” “Good point! I don’t know!” Maybe that’s for another time, or maybe that’s for the Internet, where one thing can live and float into the ether and not matter in a larger context. You can’t really do that with a book.

Also, when you try and get people to buy an essay collection, you have to give them a theme. People don’t really know me. [Joan] Didion can just say, “Here’s a book of stuff that I’m feeling.” David Sedaris just released a collection of diary blurbs. And cool, they can do that, because you are interested in their brain. No one’s interested in my brain like that. I have to give you context, and I have to give you a theme. So, if you’re not interested in stories about family, you can put the book down. If you don’t want to read about being lonely and feeling some way about identity, or womanhood, or race, you can put the book down. At least I give you something to cling to.

People don’t like talking about the marketing of books, but it’s important. It matters, and I’m really happy because nothing about the marketing or the sale or the advertising or the packaging of my book feels disingenuous. At no point was there anything where I’m like, “This is some weird marketing speak.” I’ve never had to do that.

SK: Yeah! I love the cover. That’s Scott Richardson at Random House Canada. He did a good job.

ROOM: You write so personally about your family. In one interview you said that in order to feel like you can write freely, “I have to write like they’re already dead.”

SK: I said that at a live event while they were in the audience, and I was like “Ugh, this isn’t working.” [Laughs]

ROOM: But how do you achieve that distance when you’re writing?

SK: My mom doesn’t seek my work out unless I send it to her. My dad does. This took a really long time, but there’s an understanding that this work isn’t for them. There are going to be narratives that they don’t agree with. The truth is subjective in these cases. I can say that I wrote honestly. But is it the truth? Depends on who you ask, I think. I’m sure there are people who read it and disagree with my interpretation of what happened.

My dad didn’t read the book, because I think he knew it would make him squeamish. Not for the details about him, because he loves attention. He’d be chuffed. But more because I don’t think my dad wants to read about my bushy vagina. I don’t think he wants to read the details about my labia, or when I started masturbating. These are not stories my near-seventy-year-old father is like, “Yes, that’s what I want before my death, is to read these details.” So, I think it created some space. And because my day job is journalism, I get to give them this thing that I’m not really in and say, “Just read this reporting and be happy.”

Admittedly, there are tons, tons, of stories that I will not tell until they are dead. Lots. And not just about them but about me as well, or about people in the family, or people I know. There are lots of things I won’t write just because I don’t want to answer that question. These things aren’t going away, and I don’t need to [write about them] all in my twenties, so I’ll wait. I think if you write and you’re not a little uncomfortable, it’s not working. You should feel somewhat sickly about whatever perverted things you’re putting together.

ROOM: And the reader should also feel challenged.

SK: Yeah, you should feel a little queasy. I don’t see anything wrong with that.

ROOM: That’s how you learn [laughs].

SK: I hope you feel nauseous. . . . This is a terrible interview.

ROOM: [Laughs] In your book, you wrote about how you hid your relationship from your parents for years, and the emotional fallout. What was it like to have such a big secret?

SK: It was easy! It was breezy. I was so used to it.

ROOM: Because you were far away in another city?

SK: Yeah, because I was far, and because I was used to keeping secrets from them. I’m not good at thinking ahead. Generally speaking, I can’t think more than a week in advance. It’s my best and worst quality. Because I can very much work on this thing . . . or I can be at this party, I can live in those spaces, but then if you’re like, “What’s your five-year plan?” I’m like, “How old am I now? I’ll be thirty-one? I don’t know.”

So, I found it quite breezy [to keep the secret] because I never needed to think about [the relationship] getting serious because I don’t need to think ahead. Which is frustrating for everybody else in my sphere—I was having a fine time.

ROOM: So, it was more the aftermath that was problematic.

SK: Right, because then the other problem is, when I was in the shit with my family, and they were upset, or my dad was giving me the silent treatment of the century, I couldn’t see beyond that moment of anguish. Everything felt isolated in that moment. Two weeks before, when they didn’t know, I told myself, I can do this forever. This is going to be fine.

And then I finally tell them. It was a while, admittedly [before they came around]. For my mother it was a couple months, and not like a year. But with her, being in those few months, I was like, This is for the rest of my fucking life. This is what she’s going to be like. Which is not true. But I can’t think ahead.

But keeping the lie was fine. And when my mother came into town I would be like [to my boyfriend], “Don’t call me,” and I’d hide things. It was like being in high school and still living at home and having condoms in your room, and being like, I’ll put them in this book that my mom doesn’t care about.

It was easy for me, but it was hard for everybody else. Because I didn’t have to deal with the consequences. My partner suffered—I mean I should probably apologize . . . whatever, he’s fine [laughs]. He suffered. I think my mom always had a sense I was lying to her. Moms are intuitive. But she didn’t say anything. She probably knew, and I think our relationship suffered for a long time because I just wouldn’t tell her things. But, fair enough. If your family’s threatening to throw themselves into the Dead Sea for whatever thing you’re doing, it’s probably for the best to just let them take a minute.

ROOM: Have you ever discovered a secret of your parents’?

SK: I don’t think they’re secrets, I think they’re just omissions. They don’t think about telling us. There are little fights in the family that have percolated, and I don’t have full stories about them, but I don’t think I will ever get them because half the family is in India and don’t speak English. My grandparents are all dead, so those are things I’m never going to get back.

My brother’s a real mystery to me. I’m sure he’s got some skeletons. My niece is seven now, and she’s got this really fascinating internal life. And that’s so weird to me because when you know this tiny body from a very early age, you suddenly realize, When did you decide to get a life? How did that happen?

The other problem is, there aren’t secrets among brown people. We’re not WASP-y enough to keep anything from each other. Even with my partner, I’m sure my mom had an idea because I was dating him, and one cousin knew, and she probably told her mother, who told this aunt, who told that one, who told my mom. It’s impossible. So, I don’t even know how I would keep that up because we’re so nosy. It doesn’t work. If it worked, I would have been in trouble far less as a teenager.

My mom used to read my diary. I had to start keeping a decoy diary. I once went through my brother’s stuff. I don’t know what twenty-four-year-old boy is like, “I’m going to keep this diary in plain view of my seven-year-old sister.” We just don’t keep secrets well. We’re too nosy.

ROOM: So, it’s a roundabout way of communicating with each other.

SK: No one really wants to ask. They’re just going to get it. I’m just going to go retrieve the information, and then confront you with it later. I’m a lot of fun, I’m realizing . . .

ROOM: So, you did have this indirect line of communication with your family, even if you weren’t discussing every detail. When your dad wasn’t speaking to you, then, it must have been so jarring.

SK: It was really isolating. And it affected these different parts of my life that I didn’t think it would. My dad is very invested in my job. He’s really into journalism and news. And so, when he stopped talking to me, I suddenly had no one to talk to about these stories I was working on. And nobody cares about your job the way your parent will. No one cares, about the minutiae of it, or who you’re mad at that day, little petty things. And then you’re sort of by yourself. That was uncomfortable for me. It was tough. It was lonely for sure.

ROOM: So, there you are, writing a book that heavily features your dad, and yet you can’t speak to him.

SK: The only time he really spoke to me—which really speaks to how much he loves attention—is when I asked him to write the “About the Author” section. That was my glimmer of, Oh, he’s going to be fine because when he wrote it, it made me think, Oh, you’re still in there. And then I remember relaxing a bit, and he slowly warmed up, and then eventually cracked. It just took a lot longer than I wanted it to. I would say it was a good year of it being really, really challenging. And then a couple months of him being a bit stiff. And ultimately, I have to acknowledge—and this is so frustrating, because it’s very patriarchal nonsense—but when I got engaged, then my dad fully cracked, and was like, “Great! I love you again.” Not that he said that, but that was the thing that needed to happen for him to be comfortable with it.

ROOM: Do you think not communicating with your dad changed the way you portrayed him?

SK: I think he got away with murder in this book. He comes off very well. Frankly, he should write me a thank-you note. Not that I was going to write some snide oral history about my jerk dad. But I think it made me wistful. It largely affected the last essay, because the first bunch had been written a while ago, even in pieces.

ROOM: What about how you portrayed your mom? Did you feel protective at all?

SK: I’ve always said about my mom that she’s the quiet dictator in the family. I think this is true of a lot of brown households and Asian households. Everybody thinks your dad is the one to be afraid of, but you should be afraid of brown moms. They will fuck you up. So, I don’t think she needs my protection. She will kill anybody with her bare hands if she needs to. I focused less on her because I think that’s sort of her thing. She is much quieter than my dad. She’s not as bombastic. She’s not as flashy. You don’t notice her as much because my dad’s so loud. But she is very much the one controlling these narratives and making sure we’re not all dead and that we’re still in touch. She does all that work, quietly, because that’s her way. But I think I was protective of both of them if I was protective at all.

Because ultimately, I’ve put this thing into the world, and I have no control how people receive it. And you can dislike me all you want, but they didn’t write it. So, it would feel so crummy if people didn’t like them when they read the book. I like them! I think they’re worth liking. And it’s not like I had this calamitous childhood where I was running around with scissors pointed the wrong way and eating matches or anything. I had a very regular suburban middle-class upbringing. So I had no interest in yelling at my parents for whatever dumb mistakes they made when I was a kid. But I guess protective is maybe a good word.

ROOM: You’ve said that reading Born Confused [the novel by Tanuja Desai Hidier] when you were young, and later The Namesake [the novel by Jhumpa Lahiri], were really meaningful for you. Why do you think it’s so important for people to be able to see themselves reflected in culture?

SK: If you come from a group of people who are traditionally oppressed, you don’t have a lot of proof that there’s a way out of that. I didn’t as a kid. Then, when I was older, I was like, Wow, you’re allowed to do these things and have these things?—I didn’t know that. I thought I had to be a doctor. Which, I would be the world’s worst doctor. Everybody would be dead. And almost on purpose. I don’t like touching people. I don’t like being in groups, I hate talking to people, I don’t like meeting new people. I would let them die. So, I would be a terrible doctor. But that was the thing you were supposed to do when you’re a brown middle-class kid.

It’s important in terms of perspective. Things get boring if you let the same people make the same things. That’s why we have seventy-five single-cam sitcoms where one plot is indistinguishable from the next. That’s why there are so many bad movies. It’s why a lot of books are bad. It’s why a lot of music sucks. But, on a personal level, it tells you that you can do something. You can be told that all you want, but unless you have the proof, it doesn’t mean anything.

I think that all the time about girls who might want to enter politics. I never had the gene, but, Hillary’s flawed, but man I wish you had an example of it. I wish you had something. Somebody who wasn’t a terrible example. We had a female Prime Minister for what, forty-five seconds? [Canada’s] certainly very behind on it. It’s the same thing when you look at someone like Jagmeet Singh, who I think is a deeply flawed politician, and he’s already frustrating me—politicians are frustrating, you should not trust them, generally speaking. But, it is sort of comforting. I remember when he won, I was thinking, Goddammit, thank God. Let me have this one thing. Don’t worry, I’ll get mad at him soon. But let me enjoy this for five minutes, just on this very basic level. Let me know that this is possible. Now, we’ll see what happens. We’ll see how people react to him. That makes me nervous, but that’s a separate conversation.

ROOM: You wrote a lot about anxiety in your book, but writing can also cause anxiety—writer’s block, worrying about how your books will be received, etc. Is that something you were experiencing when you wrote the book?

SK: I had writer’s block. I set time slots where I said I would write for an hour a day, or a couple hours every week. Even if I didn’t write anything, I would just make sure that I sat there and looked at the computer, and try to not play on Twitter. But at least sit there and try. And eventually, sometimes, it works.

I’m an anxious person anyway. [Writing] isn’t making it better or worse. It’s just another vessel for me to put it in. If I wasn’t anxious about Are people going to like this? then I’m sure I’d be anxious about Do they like me? I’d find another way.

ROOM: Do you have any advice for writers who feel stuck or overwhelmed?

SK: I think you should have a hobby. The worst thing I do is, I don’t really have hobbies. And it can’t be drinking. And it can’t be just hanging out with other writers. Baby Braga, who’s in the book, he runs a lot. He’s running a marathon. He’s very sinewy. I have friends who take pottery classes. So, take a language course, learn a sport, go to the gym, read. Figure something else out that doesn’t fill you with some sense of rage.

ROOM: Have you found that thing?

SK: No! I haven’t, and I don’t think that’s good. I read a ton, I watch a lot of TV, but I haven’t found something that pulls me out of that field entirely. I’m still looking for that.

I’ll figure it out. I’d like to learn a language. I think it’s important to . . . go do something else. Do something with your hands. Make friends with people who are not in your industry. You’ll go to them like, “This person was mean to me on Twitter,” and they’ll be like, “What are you fucking talking about?” You need people who look at you like you’re nuts.