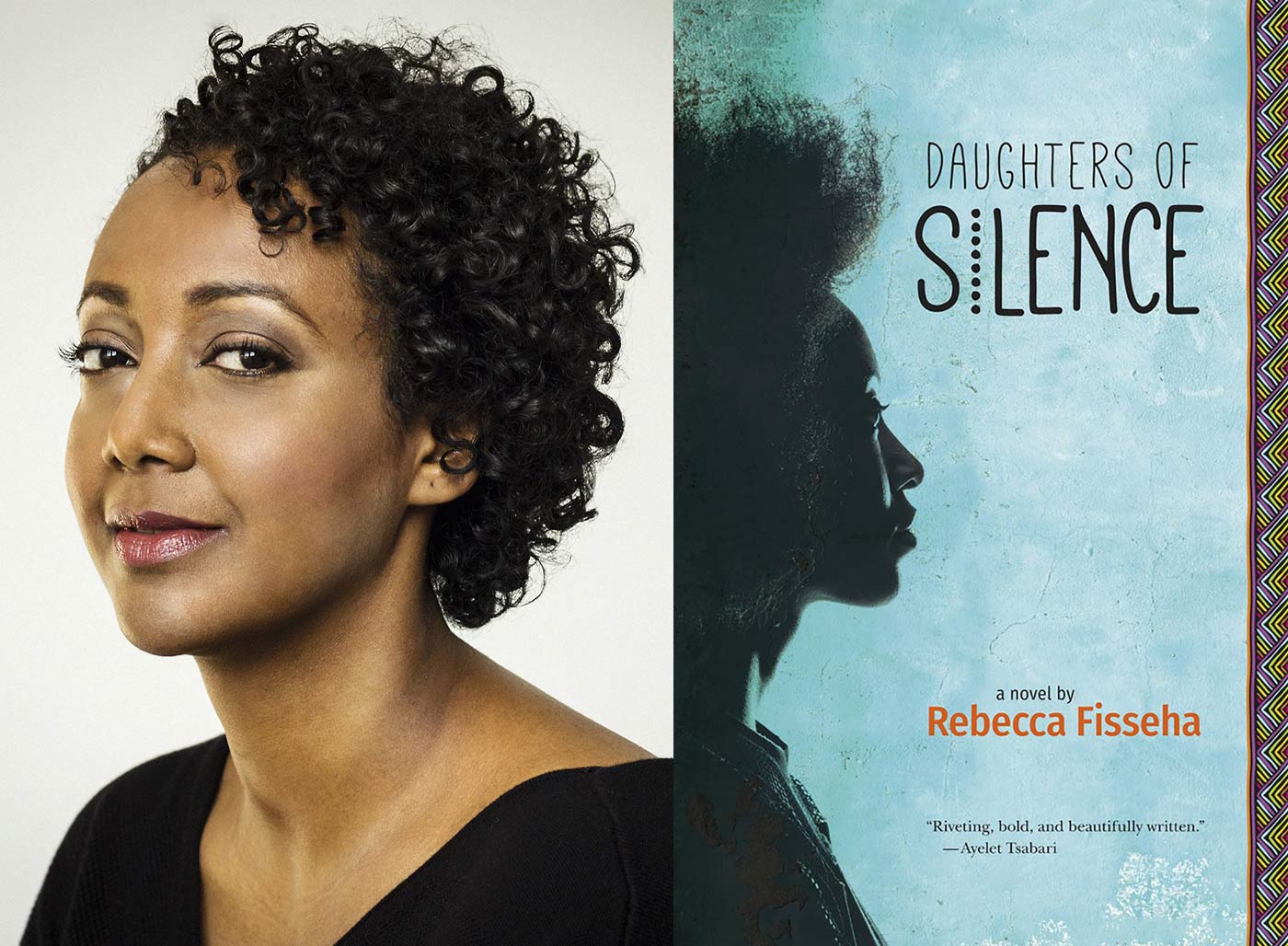

Our 2020 Fiction Contest judge and Growing Room Festival author, Rebecca Fisseha, is the author of Daughters of Silence (Goose Lane Editions), which was listed among the most anticipated fiction titles of Fall 2019 by CBC Books and 49th Shelf, and one of Quill & Quire’s breakout debut novels of 2019. Room editorial board member, Lue Palmer, took the opportunity to chat with our fiction judge and festival author about why she chose to write Daughter of Silence before any other book, writing difficult truths, and the faith she has developed for her writing process.

Our 2020 Fiction Contest judge and Growing Room Festival author, Rebecca Fisseha, is the author of Daughters of Silence (Goose Lane Editions), which was listed among the most anticipated fiction titles of Fall 2019 by CBC Books and 49th Shelf, and one of Quill & Quire’s breakout debut novels of 2019. Her short stories, personal essays, and articles have appeared in various literary journals, including Room Magazine, Joyland, Lithub, and Zora. Forthcoming is a short story in the collection Addis Ababa Noir (Akashic Books, 2020). Born in Addis Ababa, she currently lives in Toronto.

Room editorial board member, Lue Palmer, took the opportunity to chat with our fiction judge and festival author about why she chose to write Daughter of Silence before any other book, writing difficult truths, and the faith she has developed for her writing process.

ROOM: Hi Rebecca, how are you? Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me. I know you must be tired and jetlagged!

RF: Yea. But we have to do this right! Yesterday would have been impossible but today is ok.

ROOM: Firstly, Daughters of Silence is brutally exquisite. For a relatively short book (under 300 pages), it is packed with seamless history of a family, their migrations and resistance to colonization, as well as dynamic and viscerally real characters. To echo one of the reviewers on the back cover, this book really did “tear me apart and put me back together.” Let’s start off light before we get into it: what is your favorite thing about yourself as a writer and your process?

RF: I would say it is my “stick-to-itiveness”. I don’t know whether it’s because I am just incapable of not finishing something I’ve started or some other reason, but I stick with it. I keep coming back and I finish the project. I also think that it developed over time that I kind of have a trust in the process. It would feel impossible, but then I do end up with something. [And] with enough drafts in, it starts to take shape and then by the end, it becomes something I couldn’t have imagined. Because of that I’ve developed a relaxedness of “I have no idea how I’m going to do this! I have zero concept of how it’s going to happen but it’s going to happen!” I have this blind faith I’ve developed. That’s also an aspect about my process I like. And that I just have to go with whatever pops into my head. There’s this subtle instinct or voice that just says “ooh!” An idea floats in and I just go with it. I don’t say “no that wouldn’t work here” and that leads to interesting discoveries and interesting turns. I think all of these things developed over time though, over time and showing up to keep doing the work. Stick-to-itiveness is one critical thing to have or develop. Because what [the work] is now, it will transform. Just believing in it, just stay with it. It will be ok.

ROOM: Yep, I definitely relate to that feeling of “Ahhh is this ever going to turn into what I want it to turn into!?”

RF: And then in the end it does! And you are like, oh I did that! Did I do that? Urkel moment [haha] but in a good way.

ROOM: Daughters of Silence addresses community silencing in so many different ways. I know you have spoken about it before, but can you tell us a bit about why this was an important story for you to tell? In regards to Black girls and children, particularly Habesha women and community silence in regards to abuse?

RF: Well, it was an important story for me to tell because it’s the story I had to tell as a writer beginning my career. I had to get the story out before writing other purely imaginative stories. Sort of like clearing the way, getting this out, and then I can go do the fun stuff. It didn’t make sense to write anything else first because it is something that has had such a profound impact on my life—silences and the inability to confront abuse and cope with its effects, deal with it, find solutions and all of these things that I had to figure out for myself much later in adulthood. That silence, the inability to look at it and deal with it is so damaging. There’s so much waste of time and waste of relationships, what could have been. And that all trickles down to this turning away from [what is so glaringly wrong]. That’s why it was important for me to address that silence. There’s also so many aspects of my community that work toward making the girls and women sort of complicit—not complicit but kind of like they have to participate in that silence because there’s so much at stake with regards to maintaining an image, maintaining the privacy of the family, making sure nobody or nothing looks bad. I think that’s common across many cultures. That whole “don’t rock the boat” thing. In the sense that the concerns of the abused are not important really in the big picture, the big idea of the nation, the history, and the legacy. When you’re put up against all that, it feels almost selfish or self-serving to say “No, this happened to me. Look at what has happened to me. And this happened to her.” When it comes to history, politics, finances or business, these things can be talked about in all seriousness, on all big platforms. But when it comes to things that concern women, not even necessarily dealing with abuse but just the issues that affect women as human beings, they are always like “oh special category, over there.” But it’s as human a concern as everything else. And this is my way of giving it equal platform. The war between Ethiopia and Eritrea and all of that other history stuff—it’s on purpose that Dessie couldn’t care less. She’s like “oh, right, that,” because the thing that’s important to her is the personal, what’s going on with her. It was my way of saying, “well, guess what?”—while all these big world events, national events are going on or even these big family ventures that seem so important, like “oh we’re going to migrate, make a better life and we’re going to you know, make the family proud . . . ” If you pay attention to the girls in the family, that’s the last thing on their mind and they couldn’t care less. There are other things going on underneath the surface, inside that are just as important. But it’s very, very hard to make the point that the wars going on within the person, within family members are actually more important than this border shit, border wars. At least we should say, this is equally important as the officially important stuff.

ROOM: You’ve written about receiving advice from your mentor that you must “deep dive into the work and be daring.” It is hard to confront silences in our writing—especially when it comes to trauma, there’s a difficulty in naming everything and the truths we leave out. One of the things you did expertly as a writer was withhold information and then reveal it in a way that was very caring but also brutal. Can you speak a bit about the craft of doing this and the complexities of writing daring and difficult truths?

RF: It was during the last three drafts or so that I really started to consider when and how to reveal information to the reader in regard to the abuse. And it was mostly through work with Bethany Gibson, my editor at Goose Lane. I think initially I was signalling too much, hinting so heavily that it was pretty obvious what had happened to Dessie so when it was finally revealed, it didn’t have much of an impact because any reader paying attention could have figured it out long before so. It was over various drafts of knowing just how much to give and when. But it seems like even with the final version some people figure it out right away and then some people are completely caught off guard. I like the latter. But then I don’t know how you could be completely caught off guard. I think it really depends on your own background. If you have personally as a reader experienced sexual abuse, or know someone very well who has, or work with people who have, then I don’t think that person is that surprised. If you are one of the rare people who’ve never had it enter her life in any way, shape or form, then you could be completely side-swiped by it. So for myself, that’s always something that’s one of my first assumptions. I assume until proven otherwise that somebody’s been abused, unfortunately. If I see any quote unquote “abnormal” behaviour or based on certain tensions I sense, I always wonder.

Before I worked with my Karen Connelly, my mentor at the Humber School for Writers, I wouldn’t say there was much craft with the withholding information. There was just me not being able to write it, not even knowing that that’s what I was trying to write about. Then Karen said, “I sense there’s something to do with sexuality or sex.” I don’t know how she figured it out but she sort of said, “there’s something there but maybe this is not the book for it, but I’m just saying, I sense something there.” I felt like someone had just turned the light on my face, but that’s her very nuanced reading of the text. I think that withholding took care of itself over time. And then I just wrote all of it all at once—I guess I had to put it all on the page and then take it away a little bit at a time. So a lot of help from my mentor and my editor. That’s how I did it.

For Dessie herself, she’s been just in avoidance mode until the death, the funeral, and having to be around [her abuser] suddenly all the time. Up until that point, she probably has blocked it out as much as she’s able to. The pace of reveal, I wanted it to match her own pace of looking at again all she’s kept behind the curtain in her own mind. Everything is through her, as seen and felt through her.

ROOM: The way that you write trauma—the intimate parts that only those of us with this kind of trauma can know about ourselves, the texture of our fears and anger, strange habits of survival, the difficulty of physical and sexual contact—things that sometimes feel impossible to articulate outside of ourselves, you write with so much depth and clarity. What was your process like writing these elements of Dessie’s daily life, and what kind of self-care did you undertake to do this work?

RF: Well, obviously as a survivor I know how these things go. I would say if anything the process was to use myself as a starting point, to say “okay, what do I do in these scenarios usually.” Using myself as a source material. There! That’s one of my processes. And digging into memory. Trying to remember back before I had sought any kind of help because that’s the place where [Dessie] is at, right?

I wanted to show the process of how someone might just begin that turn toward healing. I’m probably about ten years of work ahead of her. Just that turn toward taking those initial baby steps so I had to sort of dig back to who I used to be, things I used to do or not do, things I used to handle or not handle. And then think of this character with her specific subtext and adapting it to her.

I don’t know that I did any self-care specifically. I didn’t even understand that it was impacting me until I would go through several days of being foggy and blue. And I was like, oh it’s because I am working on Chapter 12, when Dessie first starts to tell her story. Once I made that connection, I would hate going through those chapters again. But you can’t have everything else polished and then this part be all shitty. You have to look at it word by word, line by line, the same way you look at a manuscript everytime you edit it.

I mean I journaled a lot, I had my therapist, that helped. I didn’t really have any specific routine. Now that I have to go out and talk about it all the time, I’m starting to realize that I probably should have come up with something. Some kind of way to decompress after talking about the process. Maybe writing the book was itself an act of self-care.

If we go back to the process, one of the things that did give me a sense of liberation—because for me the constant thing on my mind was the consequences of having written this—from all of the different types of therapies I was going through, was inner child work. It kind of clicked that oh, I’m writing on behalf of the little girl, my before-girl. She’s the only one I have to answer to, really. Everybody else that were kind of hovering, the possible people that would be affected, they just fell away from importance. It just gave me a lot of courage, to just do what I had to do. Because in a way, she’s always frozen, always there. She’s a constant; she makes everything worthwhile.

ROOM: I wish we could talk in detail about the end scene of Daughters of Silence, but I don’t want to spoil anything for your readers. I can say that I read it over about six times. I have read a lot of books that deal with trauma and abuse, but none that helped me to heal as I read like this one. Briefly, could you speak on why you chose to end it the way that you did and what you wanted to get out of it as a writer and a survivor? And what you would want us to get as readers?

RF: In a practical sense I chose to end it that way to give a more complete full circle for Dessie, because one of the things I learned about writing books or novels is that you need to show the person is different from where they began. So that was an intentional decision to show that she began here, she evolved, and now she’s here. It’s a tiny circle but it’s still a circle. Before that, I was approaching it in a very realistic sense that the original ending I had was very open ended, very dark and gloomy—like who knows? I felt that was more true to life, but for the purpose of taking care of the reader, giving them that sense of satisfaction and peace of getting justice, I decided to let go and have some wish fulfillment happen, something that is so rarely available to survivors or anyone who has had some kind of betrayal or injustice done to them. How often do you get to live that out? I’ve had readers say to me, “wow that was so satisfying.” And I’m so glad because it’s almost like you can have a reckoning with almost everybody except the one person you need to have a reckoning with but you never will. So I knew it was stretching it a little bit that that could happen, even in the bounds of the fictional world, but I was like, you know what? I’m just going to let it happen. Why not! Because I can. And because we’ve earned it.

For me as a writer and a survivor it was cathartic. For myself as well as for the reader, the reasons why I did it are the same. A little bit of an exercise in fantasy, and it is healing. In therapy, that’s the kind of thing we use a lot.

ROOM: As our 2020 fiction contest judge, I have to ask—what kind of fictional writing excites you?

RF: The kind where I can’t anticipate what is going to happen. Or, better yet, where I can anticipate what’s going to happen but I’m taken completely by surprise. Or, even better yet, where the anticipated happens but then the story goes way beyond, into territory I hadn’t seen coming at all. And somehow it all feels organic, as if it couldn’t have happened any other way.

ROOM: Please tell us about your upcoming work! I understand you are working on something romantic and funny? By the way the beginning chapters of Daughters of Silence and the erotic banter between Isak and Dessie made me laugh a lot. It was very well done, so I know you have a romantic and comedic skill too.

RF: My next work is sort of inspired by, or is an out-growth of that relationship between Isak and Dessie; about relationships, diaspora and what’s normal and modern, the heritage and the messaging we’ve gotten from watching the parents and grandparents in our lives and how they relate to each other, the way love or marriage is or isn’t spoken about around us by the older people. And especially through the songs, the old ballads, the attitudes that we absorbed growing up versus the modern norms, how to relate in romance and how that creates so many miscommunications, missed connections, and complications. Once in a while though, they sync up and it’s great how we have to renegotiate how we relate to each other because the old norms clearly won’t work but there are some aspects that would be good to keep. Stick-to-itiveness being one of them [haha]. So looking at all of that stuff, but trying to do it all from a lighthearted place which I’m not very good at. Without realizing it, I find myself veering toward the serious, and have to catch myself and go no, no, no, keep it light, keep it funny!

The novel does follow a couple; that’s all I’m saying right now. I’m at draft one, though, so who knows? I’m trying not to take another eight years [haha]. I need to churn them out quicker, before people forget . . . Rebecca who? What?

ROOM: What, no! We couldn’t forget you. You write on the themes of grief, migration and diaspora, trauma, and abuse. Are there other themes you enjoy writing about?

RF: This question actually makes me laugh! Because it’s like “you love grief, trauma and abuse,” what else do you like?! Haha. It’s not like I enjoy writing about those things, it’s just that that’s what has been in front of my nose this entire time. So I would say migration and diaspora would go under things I enjoy writing about that I would like to continue writing about. All of that space of adaptation, negotiation, changing, keeping a bit of this and changing a bit of that—I’m always interested in that. Religion—I’m not sure what I’m going to do with religion but I would like to explore that some day, specifically within the context of my culture, the Orthodox Christian faith and that whole entity or institution. I had a get-together with some family and friends recently who I knew had either finished [Daughters] or were in the process of reading it and I asked them, what else do you wish would be written about specifically concerning our community in novel form. They said different things but the one that really excited me [was religion], because it’s such a huge factor in our lives. It’s impossible to get away from [even though] we lead mostly secular lives. It’s a little bit a part of Daughters of Silence in that that’s what they turn to, a sort of fix-it-all. Holy water, throw some holy water on it, there! So yeah, faith, religion, and adoption, which is a huge aspect of migrant life. So maybe one day I might like to write something on adoption, which is a factor in Daughters. It’s like all the seeds are there. Specifically who adopts Ethiopian babies? So many angles to explore within that. Which babies are considered desirable? Etc.

ROOM: Oh my goodness, yes so much could be written about that—white desire for Black babies. So, is there anything else you would love for us to know about you or about your work?

RF: Yea, everything I say just take it with a pinch of salt because I have no idea what I’m saying half the time. When I was writing the book and trying to find an agent or publisher, I used to read what other writers were saying and I would take every word like gospel, but now I realize, oh my gosh, did they feel like me? Have a healthy dose of doubt about anything I claim in these answers. Or just remember I’m still trying to figure out how to talk. The best way I’ve been able to put down anything I believe or feel is through the work. Please always trust the work before anything else that comes out of my mouth.

ROOM: I love that. Well thank you so much for your time Rebecca and for judging our 2020 fiction contest! And we can’t wait to host you in March at our Growing Room Festival! Thanks again!

This interview was conducted over the phone and has been lightly edited and condensed.

You can join Rebecca Fisseha at the following Growing Room Literary & Arts Festival 2020 events on March 14 and 15: