Jenny Heijun Wills was born in Seoul, South Korea and was adopted and raised in a white family in Southern-Ontario, Canada. In 2008, she reunited with her family in Asia.

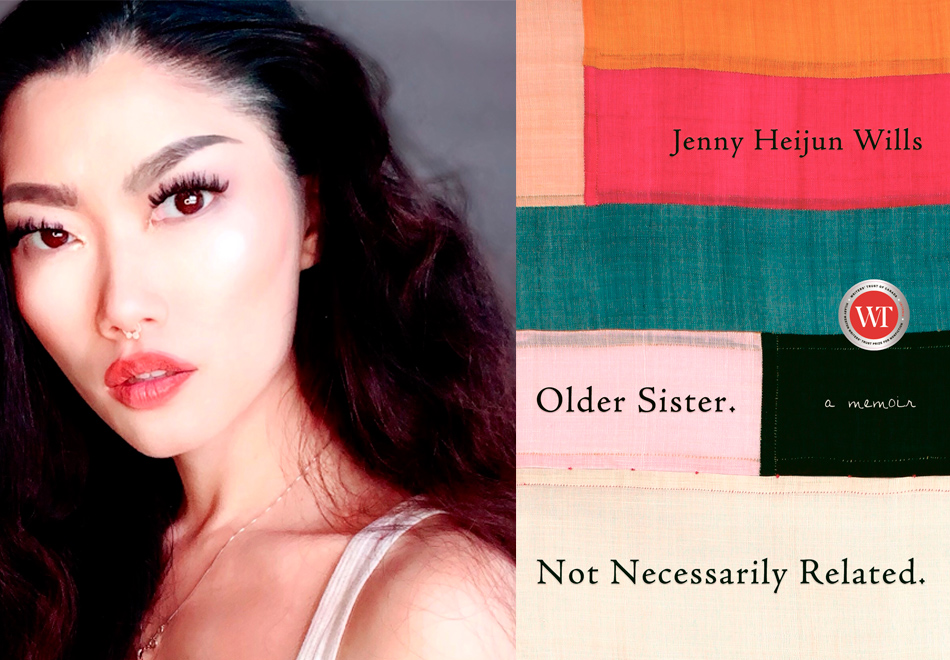

Jenny has lived, studied, and worked in Toronto, Montreal, Boston, and Seoul. Her debut memoir, Older Sister. Not Necessarily Related., published in 2019 with McClelland & Stewart, won the 2019 Hilary Weston Writers’ Trust Prize for Nonfiction and is shortlisted in three categories for the 2020 Manitoba Book Awards. She teaches at the University of Winnipeg.

She is the commissioned author for the upcoming Room issue 43.4, edited by Geffen Semach. Interview is by assistant editor, Molly Cross-Blanchard.

ROOM: Hi Jenny! First of all, I want to thank you, because while reading your memoir in preparation for this interview, I felt the first spark of “I need to write something!” since social distancing began. I know when I’ve read something important because it energizes me to create, and right now creating feels especially miraculous, so thank you.

How has the current state of the world affected your writing and, more broadly, your day-to-day?

JENNY HEIJUN WILLS: You’re very kind to offer these supportive words. I’ve followed your literary career carefully these last few years and any admiration is mutual.

Honestly, I only find the creative space to write short projects during the teaching term, but we’ll see what happens when I start my sabbatical in June. I have been reading a lot these days, which I consider research. I feel less rushed, less like I’m living from one task to the next, and then feeling guilty that I don’t spend every waking minute working on something (either for family at home or for work). Hopefully this translates to being a bit more generous with myself about work accomplishments, and puts into perspective what can (and needs and doesn’t need to) be done to feel fulfilled.

ROOM: There’s another thing that I suspect may have changed aspects of your life and work: your winning the Hilary Weston Writers’ Trust Prize for Nonfiction. Congratulations, I was so happy to read that news. What has the come-down from that recognition been like? Or the come-up?

JHW: Thank you 🙂 I was extremely surprised, not in the least because of the stunning co-nominated books. It’s a really unfamiliar world for me, so I’m just learning how to be comfortable in this role. I can be shy or nervous, but I feel extremely fortunate for all of the kindness shown to this memoir. I don’t take it for granted. The best part is meeting and spending time with BIPoC writers, feeling supported by many of them, and trying to offer support back.

ROOM: We know each other from years ago; I took your class on Asian American Women Writers when I was in the second year of my undergraduate degree at the University of Winnipeg. I once wore a Harvard sweatshirt to class, and you asked if I’d also gone to Harvard (I had, I guess; I visited my auntie there when I was sixteen and fell asleep in the front row of her business class), and I remember thinking 1) How cool it was you thought I’d gone to Harvard, and 2) How cool it was you had gone to Harvard. Your class also ruined Gwen Stefani for me forever, and good riddance!

Having read the course material you selected and heard you lecture on it, I feel like I’ve been granted a window to look in on some of your influences and inspirations—The Woman Warrior, Bitter in the Mouth, Dogeaters, among others—which I see echoes of in Older Sister, in the use of language, and the myth-making, and the dream worlds. What are some other texts you anchor yourself in while writing? Whose voices are chiming around your desk?

JHW: I realize at this moment how the small-talk outside of official class content sometimes stays with former students! What would we call this, “para-lecture elements”? My reunion story in my memoir started when I was a Fulbright student at Harvard, so your anecdote is a funny coincidence. I apologize for any other strange tangents I went down in (and out of) class. I don’t apologize for the Gwen Stefani bubble-bursting.

I definitely think about Maxine Hong Kingston’s memoir a lot because she was pushing the boundaries of the genre and also forcing readers to face their compartmentalization of all BIPoC writing into the realm of non-creative, autoethnography. I’m a huge fan of Kim Thúy, which I think is evident in the ways I structure writing. While I was writing this piece for Room, I turned to Toni Morrison, Gwen Benaway, Canisia Lubrin, and Ocean Vuong. I like to read poetry and lyrical prose when I’m writing. Perhaps I’m inspired by style and the beautiful ways politics are done by these BIPoC authors.

The book I’m working on next is in a different voice and style, and it’s historical fiction. I’m re-reading Richard Wright, jiaqing wilson-yang, Wayson Choy, Zadie Smith, Viet Nguyen, Monique Truong, and Joshua Whitehead, because I appreciate how each of these authors uses language in provocative and sometimes playful ways. We’ll see what comes of it!

ROOM: In your memoir, you use the epistolary form as a way of speaking to, among others, your unni, an older sister who isn’t physically present during much of the book. As well, your piece that will appear in Room 43.4 is a collection of tiny love letters to a chosen family of beautiful misfits (some of whom I think I recognize).

Did you always know letters were going to be part of the book? What draws you toward epistolary writing?

JHW: In my memoir, I used the second person address to say some difficult, often angry, things. Part of me sees this as a device that creates intimacy. It evokes something like trust because it might be confessional. But another part of me used the epistolary style so that I could say damning things about problematic systems and practices, not at a general readership, but at a specific person. Somehow it feels less direct, less accusatory at a reader who is maybe just learning about certain realities, if those facts are presented as whispered secrets. If they are presented as confessions between sisters of feelings of grief or rage or jealousy, maybe messages can be heard without triggering fragility or refusal. I think, then, what can be implied is louder than what might be stated outright.

If you look, some of those epistolary moments in Older Sister are extremely political. One example is about the deportation of transnational adoptees by the U.S. state and the difficult lives those people face in their birth countries for so many reasons. In the second person address, this section feels less didactic, less pontificating, than it might have, say, in the academic-style writing I do on the same topic. In other moments, I talk about violences done within adoptee communities. It felt safer to put these revelations into a performed conversation with a sister than to state them outright.

In the piece I wrote for Room… I have a hard time with emotions when I’m face to face with people. Maybe it’s a fear of rejection thing. Or a fear of loving too hard and being off-putting. Again, the epistolary is a space of comfort and safety for me.

ROOM: While I was reading the book, I made a note in the margins (I only do this to books I love) that said: “There are so many caretakers hovering around her, but never really giving her what she needs.” And then I read the new piece, which you said in your email to us might be an epilogue of sorts to the memoir, so I crafted a headcanon (is it weird to have a headcanon about someone’s life?) that these folks are the ones who were missing, and now found. They seem to be giving you what you need, if not in the way you expected.

Was there ever an “aha” moment for you when you recognized the role these other BIPoC creators were playing in your life? Or was it more like a slow burn?

JHW: Very few people know this (why would they?) but there was a moment after the first night of the Centering Ourselves writing residency at Banff (which was for BIPoC writers) where I said aloud to myself, “My life is changing at this instant. It is going to be different after this.” I don’t speak to myself often, I’m not that romantic. But I knew so clearly that some of the people I met in that residency would alter everything. And they did. Many of them are in this new piece for Room.

ROOM: With fiction and poetry, the creator can usually defer questions like, “Did this really happen to you?” and “Is this character supposed to be me?” but with memoir, there’s no place to hide. It’s one of the most vulnerable forms of expression. What has it been like to put pieces of yourself and your family into the world in such a public way, to have to answer questions about and market your own tender story?

JHW: Well, as I’ve suggested above, I have found small tricks to hide in plain sight—or at least writing strategies to feel more protected. But you’re right, it is strange to become so public in this way. Especially so since I’m pretty private about meaningful things. Sometimes even non-meaningful things (once a student said they’d read my memoir so they could figure out how old I am!).

There is also something to be said for the always-changing ways some adoptees are given information about ourselves. From one version of the past to another—because of translation, but also inconsistent memories, secrets, always-transforming versions of ourselves—there is no singular version of the truth. And many of us will never know what happened to us. I want to, at least with the preface to Older Sister, impress upon readers that the conventions of telling life-writing can be more or less vague depending on the subject’s own personal relationship to experience, singular narrative, and reality.

I actually think I held back a lot in Older Sister. I gave a lot, but I held back a lot too. The lyrical prose style, the fragmented structure, the non-linear plot—all these techniques allowed me to keep certain things for myself. Fact-based telling becomes less a priority. This is the main difference I’ve come to recognize between the academic writing I do and creative writing. Sometimes it feels like, with scholarly writing, one needs to prove all their knowledge, all their ideas, as clearly and directly as possible. With more creative modes, there is more opportunity to be evasive, enigmatic, and to build a story and character through reservation.

Of course, when it comes time to market, there are different kinds of promotional experiences. I understand that people are interested in my life story because it is pretty unusual. That my Korean parents reunited because of me, that they became a couple again while I was in Korea—it sounds like something out of a k-drama. So sometimes promotion is based entirely on my subjectivity. Other times it is more about writing and style. Rarely is it about both. People have been mostly supportive, good listeners, and not overly intrusive or entitled to more than what I’m comfortable giving.

And I understand where those other folks are coming from. Really, I do. I won’t give in to their pressures, but I get it.

ROOM: I cried a lot while reading your book, right up until the last acknowledgement. Another scrawled note, on page 98: “These breaks are like little paper cuts.” I was referring to the shape the book takes, the scraps of prose and blank space stitched together to make the patchwork quilt that is this book (which I’m realizing, as I formulate this question, echoes the cover). The way the sections staccato feels like little jabs, which on their own are bearable, but when taken consecutively make you sob.

Why did you decide to tell your story this way?

JHW: Terri Nimo is the brilliant designer to came up with the cover for the hardcover edition—and you’re right, the imagery is of a style of Korean quilting that is very popular.

I’m drawn to short, intense, moments of storytelling. These pieces are also how my memory works (and I’m sure I’m not alone)—in fragments and episodes. I think being believed and trusted is such an intense concern for some, especially BIPoC but also others, that writing in this structure felt (for me) most convincingly a reflection of memory and accuracy. Maybe that makes no sense. But I wanted to reflect as realistically as I could how my memory happens in flashes, at least so I would be believed. For those reasons, I don’t have much dialogue—because I don’t remember those details often. And things happen in scrambled orders, or are repeated sometimes, because that is also how my head functions.

I also know that believability is a systemic tool used to silence and gaslight, BIPoC, queer and trans people, other women, people with disabilities, and those with intersectional identities that combine many of these subject positions. And there is no way to defend oneself against those who don’t want to hear it or whose own identity feels put in flux by acknowledging and respecting the experiences of others. But still, this was part of my thinking.

It’s probably foolish since, as we know from people who disclose accounts of being sexually harmed, that if you explain what happened with too much fragmentation or repetition you’re dismissed as nonsensical and not believed, and that if you explain what happened with too much precision and detail you’re dismissed as a fabulator and not believed. The moments in my memoir when I was writing about sexual assault and harassment—I was particularly aware of this reality.

ROOM: You and a handful of other writers—Domenica Martinello, jaye simpson, Terese Mason Pierre—have become a cast of fashion-icons-slash-angels doing #booklooks: makeup looks inspired by the covers of work written by other BIPoC artists. I think my favourite so far has been your interpretation of Alicia Elliott’s A Mind Spread Out on the Ground.

It seems like you’re bringing a lot of joy to people in a pretty bleak time. What does this activity mean to you, and why did you decide to take it up?

JHW: Alicia has also been doing some amazing looks, and also the poet Nisha Patel, and others. Maybe it will catch on as a quarantine hobby? It started for me after having seen Terese and Domenica’s looks. It was around the time that presses started releasing spring books and I wanted to send a little glitter to BIPoC writers. It’s been a fun distraction and an amusing thing to plan, enact first thing in the morning, and laugh about. It gives me structure and pleasure, which is needed right now!

I mentioned online at some point that with the rise of anti-Asian racism I wanted to control (or feel some kind of control) over how and why people were looking at my face. I’ve done this since adolescence. If people are going to stare, I put on a kind of ostentatious disguise so I can tell myself they are staring for reasons I’ve decided on myself. I know this is just misdirection or a device for placating myself, but still I do it.

ROOM: I saw on the UW website that you’re teaching a course called “Critical Race Studies: Race, Fashion, Beauty,” which, OMG, sounds incredible. Beauty and the shame around striving for it, especially when intersected with race and culture, is something that shows up a few times in Older Sister. What’s it been like to explore those ideas with students, in a classroom environment?

JHW: Yes we just finished that seminar which was a lot of fun for me (hopefully for students too!). We discussed appropriation, stereotypes, fetishization, ableism, transphobia, and body-shaming of different iterations—recognizing the horrible impacts of those things—but really I wanted to focus on amazing BIPoC designers, makeup artists, hair artists, et cetera, from all sorts of perspectives. I worry sometimes that people think race studies is just about critiquing white supremacy. That is an important part of it, but that approach still centres whiteness and its impacts on us. It can limit narratives about BIPoC as either always angry or always suffering (I also taught a complementary course called Race and Anger this term). I wanted to do the Beauty course because BIPoC are also creative, energetic, playful, funny, inspired, self-loving, and innovative. And these are also highly political gestures, since so-called beauty standards are always shifting to disqualify BIPoC—or to steal their stuff and then change the conditions of inclusion. I wish the Hair issue of Room had been released when I was making the syllabus! Next time 🙂

I think a lot about the moving target of aesthetics. And I think about, from my small perspective, what it was like growing up without any racial references either in real life or, let’s be honest, in North American media at the time, for an Asian person to feel good about their looks. I’d be lying if I said I never stole my Canadian mother’s make up to make my skin lighter or tried to bleach my hair with lemon juice (obviously unsuccessfully!).

I also know, and I think I wrote about it a bit in Older Sister, the ironic privilege of growing into the kind of Asian-woman-aesthetic that is valued in the society in which I live. It’s confusing, feeling very ugly and then all of a sudden getting all this attention for the same thing. I had to learn that both were negative experiences, but one was in disguise. I find it complicated, explaining to the young people in my life that it’s good as BIPoC to feel beautiful in our bodies but then also cautioning against Orientalism or other kinds of fetishization.

ROOM: What’s next for you, in writing, teaching, life?

JHW: I hope to start doing some serious writing on the novel I have in mind, though I’m fiddling with structure and voice these days which has me a bit stalled. I have an academic book coming out later in 2020 and also another coming out in 2021, but my focus is more on creative writing these days (at least in terms of the new projects that I’m undertaking). Everything feels so disconnected these days that it’s hard to imagine or make plans, but in the short term, I hope to stay in Winnipeg teaching Race Studies in literature and creative writing 🙂

Follow Jenny on Twitter and Instagram @jennyheijunwills