Eden Robinson is a Haisla/Heiltsuk fiction writer known for her haunting, dark, and beautiful portrayals of contemporary Indigenous life in Northern B.C. and Vancouver. Robinson grew up in Kitamaat Village on Haisla territory where she now lives and writes. She received her BA in Victoria, and lived in Vancouver where she earned an MFA in Creative Writing at UBC. In the following interview, originally published in issue 39.3 “Canadian Gothic”, Room’s Taryn Hubbard had the chance to ask Robinson about the Canadian Gothic theme and how she sees it playing out in her past and current work.

This interview was originally published in our September 2016 issue, “Canadian Gothic.”

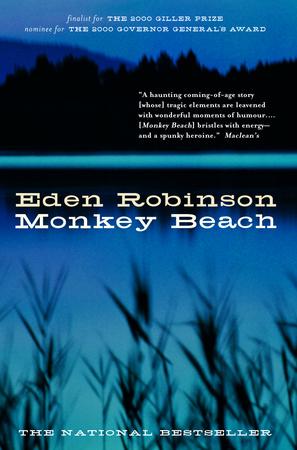

Eden Robinson is a Haisla/Heiltsuk fiction writer known for her haunting, dark, and beautiful portrayals of contemporary Indigenous life in Northern B.C. and Vancouver. She’s published three books—Traplines, Monkey Beach, and Blood Sports—with her forthcoming novel, Son of a Trickster, to be published by Knopf in February 2017. Her first book Traplines (Knopf, 1996), a collection of short stories, won the Winifred Holtby Prize for best first work of fiction. Monkey Beach (Knopf, 2000) won the Ethel Wilson Fiction Prize and was nominated for the Giller Prize and the Governor General’s Award.

Robinson grew up in Kitamaat Village on Haisla territory where she now lives and writes. She received her BA in Victoria, and lived in Vancouver where she earned an MFA in Creative Writing at UBC. In the following interview, Room had the chance to ask Robinson about the Canadian Gothic theme and how she sees it playing out in her past and current work.

ROOM: Why do you write?

ER: It’s a hoot. I have a lot of fun writing. It satisfies a lot of creative urges.

ROOM: Near the beginning of Blood Sports you have this fantastic description of Commercial Drive in the late 1990s. There’s Grandview Park, coffee shops, and the hustle and bustle of a much-beloved street. What do you think of East Vancouver’s increasing gentrification?

ER: Well, a) it’s not as affordable as it used to be, but I think that’s true of all of Vancouver and b) I hope pretension doesn’t get in the way of good coffee.

In the 1990s, you could still hope to own a handyman’s special in East Van. Today, if you have a minimum wage job, you have no hope of owning a house, or even a crappy, crate-sized condo. I found the end of my time in Vancouver in the late ’90s increasingly fraught, and I love the city, but it took a lot of hustle to keep afloat.

ROOM: Families come up a lot throughout your work. What draws you to write about family?

ER: The dynamics are always fascinating. Dysfunctional families are all dysfunctional in their own unique ways. Like the Kardashians. Sure, they can be awful people, but their awfulness has moments of recognizable angst: sibling dynamics, mother-daughter bonds, blended families. Seeing ourselves reflected in people that are nothing like us is exciting and horrifying.

ROOM: This issue of Room is dedicated to the Canadian Gothic. Critics have described your work as having gothic elements. How would you define Canadian Gothic? Is there such a thing?

ER: I hate to be all Atwoodian, but in Canadian Gothic, our landscape is our haunted castle. The monster in the background is the sheer scale of non-human landscape surrounding our characters. Weather channel, anyone? Hostile winters, extreme summers, unforgiving wilderness. Our increasingly urban population will most likely be reflected in our changing literature, but once you wander away from the cities, you realize how intimidating our wilds are in scope.

ROOM: How do you see landscape working in your writing?

ER: Sometimes it shows up and sometimes it doesn’t. Sometimes I have an easy time getting it in the story and sometimes I don’t. The last book I set in Kitimat, and because I live here it’s super hard to describe it.

ROOM: You would think it would be easier . . .

ER: It’s almost like describing tying a shoe. You do it without thinking. It’s a landscape that I take for granted. When I sent it out for first draft, the comments were “this could be anywhere, what specifically makes it Kitimat?” When I was working on Monkey Beach, I wanted to describe the landscape of the territory, which was harder and easier because I was trying to give additional back story to the description. It took a lot of fiddling to get the tone right. My more urban stories tend to lend themselves to landscapes that are more gritty, especially for the settings that I chose for Blood Sports and some of the early short stories.

ER: It’s almost like describing tying a shoe. You do it without thinking. It’s a landscape that I take for granted. When I sent it out for first draft, the comments were “this could be anywhere, what specifically makes it Kitimat?” When I was working on Monkey Beach, I wanted to describe the landscape of the territory, which was harder and easier because I was trying to give additional back story to the description. It took a lot of fiddling to get the tone right. My more urban stories tend to lend themselves to landscapes that are more gritty, especially for the settings that I chose for Blood Sports and some of the early short stories.

Now the book I’m working on, Son of a Trickster, starts in Kitimat and the second book is in East Van, and it has a much lighter feel.

ROOM: Is it the East Van setting that has a lighter feel?

ER: Yes. Son of a Trickster is a cognitive screwball gothic with working class people and they are bouncing off each other. It was a lot of fun to write. It’s coming out February 2017. I finished it last year and then I started working on Trickster Drift, which is the sequel.

ROOM: In many of your interviews, you mention letting your writing rest, putting it away for a while. Monkey Beach took ten years to write. How does time help your writing process?

ER: I’m a leisurely writer at the best of times. When I’m making a technical leap though, the process slows to a crawl. Before Monkey Beach, I hadn’t written a novel and everything about the process was new and demanding.

Right now one of my rough drafts has multiple narrators, which is a first. Usually I stick to one person’s viewpoint. I’m finding the head-hopping non-intuitive and frustrating, but it’s a sprawling, community story and can’t logistically fit into one narrator’s point of view. What to do? I’ve put it aside to let it simmer on the back burner of my mind until I’ve read some more novels that have multiple narrators roughly in the manner I want to write my own novel.

Without time to mull, every book I write would be the same. Why bother? If it isn’t exciting and challenging, what’s the point?

ROOM: When you’re working on a novel, what kind of research do you do?

ER: For novels, I fill my head with random bits that feel intuitively connected. Much like planetary accretion, once I have a critical mass of material, the gravitational weight of ideas collapses into a ball, and the story starts to spin.

For instance, I’m currently interested in coronaviruses and the medical research done to First Nations students from residential schools in places called prevatoriums.

Ebola may be gruesome, but until it becomes more easily transmittable, it’s not going to be an effective world-ender. Coronaviruses, on the other hand, have a proven track record. The Spanish flu? Coronavirus. SARS? Coronavirus. All the exciting emerging respiratory illnesses that have the potential to drown your lungs in your own mucus? Coronaviruses.

I also have a lot of stories rattling around my head about the bizarre medical treatments for tuberculosis some of the prevatoriums tried on their First Nations students. I’m not sure what kind of story would come out of these interests, but my process for research would simply be to read, read, and read some more. Listen to stories from residential school survivors and pounce on virologists when the opportunity presents itself.

The Zika virus has just been fascinating. All over the news and just the way it has the power to reshape humans. I think viruses actually reshape your body like Ebola. I was reading this book that had a virus that gave the characters the power to shape shift.

ROOM: In the Walking the Clouds anthology edited by Grace L. Dillon, the introduction to your sci-fi story “Terminal Avenue” says “Robinson offers a snapshot of violent oppression glossed by reflections that reflect the colonized state of mind.” Violence, in physical, mental, and emotional ways, reoccurs throughout your work. Can you talk about violence?

ER: Well, all writers have innate talents. I’m horrible with erotica, but violence comes easily. It’s actually a default mode that I have to fight. I worked hard on my dialogue and am comfortable with it as a skill set, and have to force myself to write description, which I find painful.

I also think our current society is only possible through oppression. Our clothes are sewn in sweatshops. Our meat is factory farmed. The resources we use in our technology and vehicles are stripped from indigenous land bases around the world—loot and leave the mess for the locals. The economic meltdown in 2008 seemed to evaporate our collective conscience. We were so focused on economic wellbeing, social justice issues got shoved deep into the background and became not just unpalatable, but unpatriotic.

ROOM: Here we are eight years later. Do you still see our social issues being pushed into the background?

ER: I think they are being dragged to the forefront. Black Lives Matter, the trans bathroom issues, the whole spectacle of Trump. What they didn’t like about the last federal election was the complete absence of poor and working class people. All the public geared toward the middle class, the middle class, the middle class. Us, the millennials, new immigrants, everyone that didn’t have an economic voice was being vanished from the political landscape. Jobs now are precarious.

People I know in Vancouver have two to three jobs to keep up their apartments. A lot of Canada’s working class and people under the poverty level—their work is not valued. They are keeping a lot of industry going but they have no security, they have no medical, very little options for child care, so there is a huge economic divide in Canada and it’s going unacknowledged. It’s happening right now in the U.S.A. with Bernie and Trump, and I find that exciting. Because they have long-standing issues from the 2008 election with a lot of people not benefitting from the upturn in the economy since.

Also, Attawapiskat and the issues of remote Northern reserves not having as much funding as people in cities or reserves closer to urban centres. Having complete economic and political disadvantages and the despair that comes with that. Those issues are bubbling up, but they are bubbling up in crisis mode. They are not bubbling up because we are tackling them. The young people are coming to form a suicide pact and deciding to end their lives. There doesn’t seem to be progress unless there is a crisis and that drives me nuts. What I’m saying is that, the social issues are coming to the forefront. It’s begrudging, and inspiring to watch it being mirrored in the States with Black Lives Matter. There was a sports commentator who wore a Caucasian shirt and there was a backlash that he was being racist, and I found that pretty amusing.

ROOM: In Blood Sports, you have this amazing experimental film script-style section. As I read it, I found the sparseness of the transcribed evidence tape and its developing narrative chilling. How did you find the process of storytelling this way? Any film script projects on the horizon?

ER: I tried a number of different styles, but the script was the one that captured the banal awfulness of stalking in ways that other techniques didn’t. I love writing scripts, but hate meetings. I love the solitary process of novel writing, rattling around my own brain until I have something hammered into a reasonable shape.

ROOM: When you’re busy working on a new writing project, what’s your daily routine like?

ER: Up at 5 or 6 a.m. Writing for two or three hours. Then answering emails, and then running errands. I freelance, so whatever contract I have determines my day job. In the evenings, I tend to mull and do research.

ROOM: How do you keep your writing exciting and challenging for yourself?

ER: Just by not repeating myself. I enjoy writing dialogue and menacing moods, but I try to push away from them and try new things. I read a lot of writers who are writing with the skills I want to use. This year I’ve been expanding my reading beyond North America because most of my reading comes from Canada or the United States. So now I’ve read Norwegian writers, European writers, Australian writers, basically trying to get myself out of just sticking with North American writers. I know so many writers in Canada and the States and they are doing some interesting things, so picking the next book is always a challenge. You think, “okay, you have this many hours . . .”

ROOM: What have you found from this year of expanding your writing?

ER: Mostly I’ve been focusing on writers that are trying to write the community story. A story from the point of view of the whole community, so I’ve been seeking out writers who are writing about their communities. There are a bunch of technical challenges writing about community, and also ethical challenges. I’m always curious to see other people deal with the same issues—or similar issues—that I’m dealing with. I’ve also been reading a lot of poetry. I really like this book edited by Neal McLeod called Indigenous Poetics in Canada. There are serious essays in there, and the work ranges in tone and subject matter. Lyric Philosophy by Jan Zwicky is a book I go to when I’m stuck.

ROOM: Final question—do you like Elvis? He pops up as a clock “mid-gyrate” in Monkey Beach and there is a reference to Jeremy “dancing to the jailhouse rock” in Blood Sports.

ER: Yes! If you grew up on the rez, Elvis was everywhere. My mom is a huge Elvis fan, and so were her friends and a bunch of our cousins. He was the soundtrack to a lot of family gatherings. Also, there’s an unspoken rule in Indigenous fiction that you must have one Elvis reference or face union sanctions.

Photo: Arthur Renwick