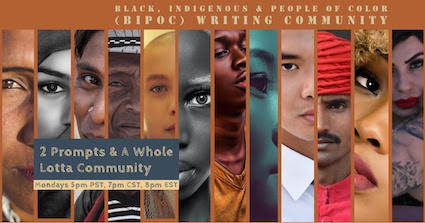

[The banner art featured in this article is made by Faith Adiele.]

Microphones go off mute. Gazing upon the activity across the gallery of attendees on the screen feels like facing the facade of a window-paned high rise at night. Some panes are opaqued or still while others catch the eye with movement. The mood is anything but one of solitude or isolation. A keen observer will notice a friendly feline saunter into view. The break, after an initial writing prompt session, rings with laughter, joy and delight. An ensemble of Black, Indigenous and Peoples of Colour (BIPOC) celebrate the craft of writing with each other at one of the weekly BIPOC Writing Community virtual writing parties taking place since March 23, 2020.

Faith Adiele, professor at California College of the Arts and author of Meeting Faith, and Serena W. Lin, a California-based writer and attorney, hosted their first BIPOC Writing Party soon after the State of California mandated a state-wide shelter-in-place order due to COVID-19 on March 19, 2020. They planned the event to provide a quiet space for peoples of colour interested in writing to focus and relax from all of the stress of the pandemic. Word of the event spread through Faith’s and Serena’s social media circles. The next week, they hosted the BIPOC Writing Party Part Deux, then scheduled subsequent writing parties for every week in April.

In the fall of 2020, I meet with Faith and Serena over a video conference while they take a break to chat with me and get a bite to eat between their busy schedules. Serena answers questions between bites while Faith joins from her car while she finishes eating. When asked who came up with the idea for a writing party, Faith, says, “it was Serena’s idea.” Serena laughs away the implication of having cajoled Faith into co-hosting the event series. Their friendship stems from VONA (Voices of Our Nations Arts Foundation), the only multi-genre workshop for writers of colour in the United States.

Serena recalls the shock of the pandemic, the realization it would be difficult for her to write in the face of such overwhelming change. She felt the same would be true of other writers, especially writers of colour. Serena says she told Faith, “let’s host this . . . Some of our close friends will come. We’ll all write together. It’ll be awesome.” When Serena called her, Faith remembers saying, “I can’t write. I’m blocked.,” but Faith felt she could think of ways to help others write and focus. Serena credits Faith with recognizing the need for a recurrent event, a regular, stable space for BIPOC writers, a need that became all the more real in the wake of George Floyd’s murder on May 25, 2020.

For Serena, writing is an act of connection. She affirms how the act of writing with others has deeply connected this group, thousands of miles apart, struggling with alienation, through the pandemic and during the biggest civil rights movement of her lifetime. We discuss the need for writing spaces specific to BIPOC writers and how, for a non-writer of colour, this need may seem counterintuitive to forming a collaborative writing environment. Faith explains how privilege normalizes an individual’s reality in such a way that it limits what they see and don’t see, and, since they don’t see anything else, they don’t perceive a need for it.

Faith:

“It’s so easy to be blind and not see other folks’ entire realities . . . They have no understanding of the kind of spaces we [BIPOC writers] need that can nurture our voices where we don’t have to be translating our experience, we don’t have to be writing to a perceived sort of POC experience, but we can just really do what we want to do with support.”

Serena:

“It’s about having the support as a writer of colour to create . . . Look at the pandemic when it first happened . . . It’s [claimed as] the pandemic without any sort of respect to region or geography or identity, but the impact of the disease has been clearly harder in communities of colour . . . There’s so many ways in which we are constantly as writers having to defend in both our creative lives and our everyday life that race matters, that race disproportionately affects [the BIPOC community], that being of a certain race means that you will face more negative impact.”

Serena describes how a shared understanding that race matters helps BIPOC writers move past a tired, antagonistic argument into creativity, freedom, support, even love and respect for each other as artists. In line with the sentiment of mutual respect, Faith and Serena established a commitment to a safety statement which is read at the beginning of each event and is displayed prominently on the community’s website. Serena credits Faith for most of the language of the statement and the underlying understanding of an evolving writing community, one whose membership takes responsibility for growing together as a group and affirmatively communicating with each other in a spirit of support. Serena reiterates that the BIPOC community is composed of peoples of colour having very different experiences and backgrounds with differing relationships to their BIPOC identity.

There are two writing prompt sessions per event, led by the co-hosts and an occasional guest host to give the co-hosts time back for their own body of work. By inviting guest hosts, Faith and Serena affirm their guiding principle of highlighting other writers of colour and supporting their work, particularly debut works. Guest hosts also provide a variety of prompts to attendees. In addressing how the prompts were generated, Faith shares, “I wanted a language for our particular crisis but I also wanted to have an opportunity to take refuge or have a respite from it, too, so maybe we’re doing something fantastical or funny . . . I also wanted it to be topical if folks wanted to do that.” Faith feels the process of anticipating the needs of other BIPOC writers helped her heal from “shutting down” as a writer. Though she never enjoyed prompt-based writing in the past, Faith speaks to how in this moment, when the world is so overwhelming, there is something about how prompts offer an opportunity to focus on something small. She recounts how something opened in her and allowed her to write short essay works when she returned to the prompts.

Serena and Faith reminisce about the twenty-fifth anniversary writing party celebrated on September 7, 2020, and how they continued to co-host until September 28, 2020. When asked about a standout moment, Faith laughs and says, “everything was amazing.” Serena adds, “working with Faith.” Watching and listening to Faith and Serena interact, it seems like they must have worked with each other on many occasions. However, co-hosting the BIPOC Writing Community writing parties was their first time working with each other on a project. Together, Serena and Faith co-hosted for twenty-eight consecutive weeks. Their synchronicity led them to decide to step back as co-hosts and hand-over their roles at the same time.

The BIPOC Writing Community writing parties continue, co-hosted by Miguel Angel Angeles, a queer Xicanx writer from California, and Faria Ali, revived fire sign writer who spends time in Brooklyn and central New Jersey. A month after I met with Faith and Serena, I meet with Miguel and Faria, after they host one of the weekly Monday night BIPOC writing parties, to talk about their transition to co-hosts from participants. Faria describes attending the first writing party through Serena. She recalls needing the structure in March 2020 because of the threat of the pandemic; she appreciated the warm, friendly and affirming community as well as the twenty-minute writing sessions. Miguel recalls the anxiety of living alone in Staten Island, losing his job and moving to California; the BIPOC writing party gave him the opportunity to build the virtual community he needed and to which he would frequently return.

Faria:

“I love the composition of this group . . . I don’t think I would ever get to write with this kind of a group, super inter-generational, geographically distributed. If I was in New York City, it would be a lot of people who look like me or are around my age.”

Miguel is not new to creating prompts, having created prompts for the NY Writers Coalition. He describes how during his transition from participant to host he found himself more aware of the group’s needs and attentive to what was being shared within the group. Miguel says, “it’s helped me to think not from a writing perspective, but from the perspective of creating something for other people to create.” At the end of the BIPOC writing party, attendees opt-in to share something they wrote in response to one of the prompts. Faria describes how as a participant, the prompts exposed her to other styles of writing and informed her ability to generate prompts for this space as a co-host, enriching her daily writing practice.

We discuss the advice they would give to others wanting to create a similar space. Miguel and Faria describe how they embraced and adapted the structure of the BIPOC writing party created by Faith and Serena to their own leadership and collaboration style while maintaining the fluidity of the event. They remember initially adhering to the schedule like clockwork — introductions followed by the first prompt, a break, the second prompt, then inviting attendees to share their writing with the group. Miguel emphasizes the importance of learning how to work together and learning what works for each other.

Miguel:

“I think logistically that [the structure] is all really important, but just as important is the banter, the going back and forth, people getting a chance to chat with each other . . . One of the conversations we had with Faith and Serena was that the time is really important. If we are saying two hours it’s really important to do the whole two hours because people are coming in and looking forward to having this space from 5pm to 7pm [PST] . . . One thing really important is to be flexible, to figure out what it is you really want and that you may not know exactly what you want when you are starting something so be willing to go with it and change it as it goes.”

Faria and Miguel stress the value of the community itself. The BIPOC Writing community has volunteers who assist with a reading series, social media marketing, website design and technical support. Faria highlights the “natural sense of community ownership that grew over time.”

Miguel credits “the sense of teamwork and the sense of the community . . . All of us [BIPOC Writing Community members] stepped up when Faith and Serena stepped down. It’s all been very lucky to have.”

Back at the BIPOC writing party in session, during the break, my thoughts return to my initial conversation with Faith and Serena. I am reminded of the theme song from Cheers, the American sitcom, the appeal of going somewhere where everybody not only knows your name, but can pronounce your name correctly and are genuinely glad you came. This is what it feels like to attend a BIPOC Writing Community writing party. The break is over. I listen to the reading of the second prompt as it is shared on the screen. As I reflect on the prompt, I recall Miguel hoping the pandemic is not the end of this community or something like it. I’m inspired by the dedication of Miguel and Faria to continue this work. As I write, the words of Faria, Miguel, Serena and Faith resonate within me.

Faria:

“This is one of the only spaces I have away from white people. I feel really different in it . . . It feels different in a life affirming, really important way.”

Miguel:

“It is a very queer and trans-embracing group. I am very happy it has turned out that way.”

Serena:

“I am grateful for the people who showed up. It was heartening to see those faces.”

Faith:

“The work that we’re doing right now during pandemic, the work of artists and writers is critical historical documentation so we actually have to be able to do this to capture this narrative of what is happening to communities of colour under this pandemic, under this racial reckoning, all of it, it’s not even that we’re doing it for fun to write. This is the record.”