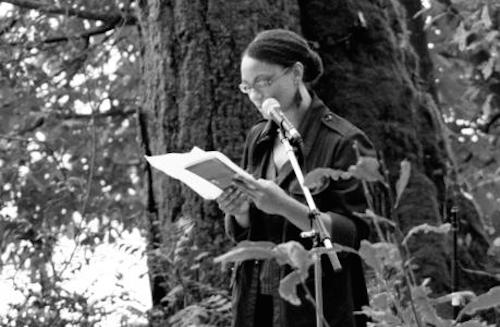

From issue 37.4 Claiming Space, Room editor Christina Cooke talks with poet Cecily Nicholson.

From Issue 37.4 Claiming Space, December 2014

Cecily Nicholson’s work, both creative and social, engages conditions of displacement, class, and gender violence. She is the administrator of Gallery Gachet and has worked in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside neighbourhood since 2000. She is the author of Triage (2011) and From The Poplars (2014), both from Talonbooks. Here, she gives us a peek into the threads that pull her writing and her activisms into harmony. Some interviews begin with discussions of cats. This interview began with a discussion of buttons.

CECILY: Sometimes I get possessed to change all the buttons on a whole item of clothing. I love buttons, I keep a button collection. Apparently I’ve loved them since I was a child. [pause.] Is this being recorded?

ROOM: Yup.

CECILY: [laughs] Cecily Nicholson, serious poet and activist, loves buttons.

ROOM: Room magazine, serious feminist publication, loves Cecily Nicholson! We recently featured your newest book From The Poplars in our online post “14 Books To Watch Out For This Year,” as well as in our literary roundup of black Canadian authors during Black History Month.

CECILY: Those were both so nice to see, especially the Black History Month post. In my public literary life, being black is something that’s not been much of a focus—as much a result of my own issues with the public identity of black as it is an external reluctance for a publishing world to reify my blackness. For myself, being seen as black has never been the main filter for how I’ve wanted to write. I don’t just mean blackness, but also the idea of hybridity, which is something I embody when it comes to racialization, culture, sexuality, and patterns of migration. These factors foster a fluidity in my modes of being. To use a multicultural term, my cultures of influence are quite “diverse.” It’s never been easy for me to be so forthright with my blackness, especially coming into Vancouver and learning what “black” means within this city’s context. It’s taken years of adjusting and exploring those nuances, but I’ve reached a point where it’s easier and owned—and I love it.

ROOM: Has blackness since become a lens that you write through?

CECILY: Let me just say that it has been there all along. The crucial factor I’m disclosing here is that I’ve not always legitimized my own experiences as being part of that cultural legacy. What has become more pronounced is my understanding of how to talk about blackness and diaspora, what it means to a public, and the ways it flows through my everyday interactions. Seeing subjectivities actualized is a prevalent theme in much of my work.

ROOM: How so?

CECILY: From The Poplars, for example, is an effort towards building an active subjectivity that’s located on land, as well as within histories of settlement, migration, and brutal erasure resulting from colonialism. The poetic lens within the work is multifarious and fractured, in a good way. It includes migrant narratives, which stem from me—particularly the thread that draws on legacies in proximity to Detroit. It’s hard to summarize, so if folks have the means and the time, they can learn more by reading the book.

CECILY: From The Poplars, for example, is an effort towards building an active subjectivity that’s located on land, as well as within histories of settlement, migration, and brutal erasure resulting from colonialism. The poetic lens within the work is multifarious and fractured, in a good way. It includes migrant narratives, which stem from me—particularly the thread that draws on legacies in proximity to Detroit. It’s hard to summarize, so if folks have the means and the time, they can learn more by reading the book.

ROOM: How does that concept translate into your other work, if it translates at all?

CECILY: Outside of my writing, my paid work currently has me in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside as an administrator for Gallery Gachet, where I work with people who call this community home and create applied arts. I feel very much a part of the community here, in part because the Downtown Eastside holds so many peoples that have been displaced, such as former wards [of the state]. I’ve come to realize that having been a ward comprises a significant component of my identity. We all have relationships to the state, whether as wards, migrants, First Nations peoples, refugees, etc. Understanding those relationships within the context of the Downtown Eastside adds a certain reciprocity and growth to my literary work, which I am grateful for.

Various streams in my first book Triage run through the Downtown Eastside: working through trauma, bearing witness, shared narratives, and resilience. That kind of book I don’t think I can do again. It is specific to who I was following that period of my life, and was a necessary endeavour to keep me going as a writer. Trauma needs to move through the body and the brain in order to become something different, something other than cyclical, triggering, self-focused destruction. If trauma has to be “something,” I want it to be something generative. That’s what Triage represents. In the years since, I’ve been very deliberate to not write explicitly about the Downtown Eastside. There are a number of poets writing about this community who live and work here in more sustained ways than I do. Though my writing exists in concert with the everyday realities here, I don’t want to be a voice for this community; my layers of privilege and part-time association with this land—I live in New Westminster—makes that affiliation a proud but complicated one.

ROOM: What is it about Gallery Gachet that makes you so excited to work there?

CECILY: I enjoy its self-identification as an outsider arts space. The dichotomy between “inside” and “outside” can be easily broken down, but what’s important is that Gachet doesn’t operate as a formal institutional space. I enjoy Gachet’s feistiness and its mandate to make space for discussions of mental health. Those sorts of discussions aren’t usually or decently highlighted in the arts, or in society as a whole. The stigmas attached to mental health are pretty devastating given how the conditions that spawn mental illness become normalized, and the resulting actions of some living with mental illness are unsanctioned and criminalized. Working in a space [like Gachet] that works with those who experience all this and still make art is really powerful. It’s not easy, by any stretch. It is worthwhile.

ROOM: That’s great!

CECILY: I feel like I skirted that question.

ROOM: Perhaps …

CECILY: I’m reluctant to centre on myself. One of the key questions I ponder at Gachet—which is also one of the reasons I’m invested in their work—is: what does it mean to champion a space that provides capacity for working through histories of trauma? There’s something special about having that aspect as part of my everyday work environment. Yet it shouldn’t be special.

At this point in my life, it’s pretty important that where I work has an understanding of the necessity to balance out histories of trauma and ways of attaining sound health: I don’t wish to be in an environment where I have to hide wounds and scars, or devalue my contributions because of them.

ROOM: Absolutely. You’ve mentioned quite a few threads that flow through your everyday living. What do you see—if you see any at all—as being the “thing” that binds everything together?

CECILY: I would articulate that as a call—not in a religious sense, but as an ongoing commitment to engaging with community when we need answers to injustice. It’s a deep-seated need that pushes me out of my introversion and toward regular and organized interactions with people. Being social is not my natural state! I also see this as generational: I see myself as part of long lines of people seeking solace and truth, a legacy that extends far behind and beyond me. That “thread” is critical. I love it, and I love when I recognize it in others. It’s not easy: always caring, constantly seeking answers to what’s really going on. It would be easier to look away, to disengage, stare at our phones (should you have one)—those sorts of gestures render people invisible. It is critical to listen for narratives that have been silenced, to centre people who are often made marginal, and address these conditions with a sense of responsibility and with action. Of course, it’s not possible to address every situation—we try. I think that’s a better life.

ROOM: Does that “thread” touch down in your poetry?

CECILY: Absolutely. I do like to think about poetry and what it means for all of us. Right now, the resurgence of Indigenous intellectual works and poetics is a powerful and necessary intervention. This work has always been there. In recent years some beautiful and robust entities have surfaced. This is a crucial venture in poetics for all to sit down with and learn and listen— especially to what’s being done with languages that aren’t English, as well as to languages that aren’t “proper” British English. After being heavily steeped in predominantly white European poetics and knowledge during my whole schooling, non-“proper” and Indigenous poetics are still fairly new to me to study; I’m still working through the layers. At the same time, as contradictory as it may seem, these sorts of poetics are also the threads that connect me to the governmental state.

CECILY: Absolutely. I do like to think about poetry and what it means for all of us. Right now, the resurgence of Indigenous intellectual works and poetics is a powerful and necessary intervention. This work has always been there. In recent years some beautiful and robust entities have surfaced. This is a crucial venture in poetics for all to sit down with and learn and listen— especially to what’s being done with languages that aren’t English, as well as to languages that aren’t “proper” British English. After being heavily steeped in predominantly white European poetics and knowledge during my whole schooling, non-“proper” and Indigenous poetics are still fairly new to me to study; I’m still working through the layers. At the same time, as contradictory as it may seem, these sorts of poetics are also the threads that connect me to the governmental state.

ROOM: That’s probably true of any settler poet who calls this land “home,” don’t you think?

CECILY: Good point. I suppose a difference is that for some, it’s totally okay to be characterized as “Canadian.” They see no reason to question that designation. For others, though, that designation makes no sense and never has. It’s almost laughable to me that being “Canadian” is supposed to mean so much in relation to literature. I’m not suggesting that I don’t want to be part of that conversation or that those conversations shouldn’t exist, but it certainly doesn’t make sense as a main category or affiliation.

ROOM: Where would you contextualize and locate your work, then?

CECILY: I see my work as taking up calls from beneath the city, from the land. Listening recently to Sarah Hunt and others, she reminds us to open to the lessons from underneath and beyond Canada and the cities—I appreciate this language—and to the Indigenous knowledge in the land. I don’t take up land-based storytelling or Indigenous storytelling. This is not my land or my territories. This is not my story to tell here. Instead, From The Poplars, in breaking down the colonial settlement and the devastation wrought by industry on Poplar Island, and how that underpins New Westminster as a municipality now, requires connective threads in the work to necessarily stretch through the concrete and into the earth itself. Generally in my work, I never want to forget the elemental land.

As someone who grew up in the rural and always outdoors, it’s important for me to take in the scent of rivers and feel the bark of trees in order to stay alive and keep myself grounded. If I didn’t have any concern for politics and my values were superficial and stunted, I’d probably just write unquestioning poems about nature, or perhaps I wouldn’t write at all.

ROOM: With that in mind, how would you describe your place within current poetic movements? Basically, what are you trying to do with your work?

CECILY: One of the central imperatives in From The Poplars, which is deliberately understated, is the idea of sensitizing. I see a crisis in people’s capacity to feel. So many of us are completely turned off to what’s happening around us. Those of us who are turned on at worst are killing themselves, grinding themselves to the bone to create change. People need to step up, and they need to feel the reasons. I hold to the possibility of liberation for folks in my historic and diasporic communities, for my local and Indigenous networks, and for myself. I experience this as something joyful.

ROOM: Really profound.

CECILY: Thank you.

ROOM: Thank you for speaking with me!