From 37.3 Geek Girls, an interview with comic artist and writer Emily Carroll. Carroll has been a prominent voice in the web comic horror genre since her work “His Face All Red” went viral during the Halloween of 2010.

Emily Carroll has been a prominent voice in the web comic horror genre since her work “His Face All Red” went viral during the Halloween of 2010. Her beautiful, yet delicately sinister, fairy-tale comics evoke a feeling of isolation that twists into suspense as the reader clicks and scrolls through a horror story and that lingers in the mind long after the final panel. Based in Stratford, Ontario, Carroll’s award-winning works have moved from the web and onto the printed page in books and anthologies published throughout the world. Her first book, Through the Woods, was published this past July. Find out more about Carroll’s work at emcarroll.com.

ROOM: I read you use a nib pen, paint and Photoshop to create your art, but I was wondering if your style was referencing more traditional art making practices, particularly printmaking or woodcuts, as well?

EC: I used to be very much into Japanese wood block prints from the 19th century. It hasn’t been a conscious decision to incorporate those elements into any of my work, but I am certain that it is still an influence since I was really into it; that kind of graphic quality and the strong black line and the pattern. With a lot of the materials I use or how I approach the art, I will change what I’m doing based on artists that I’ve seen or things I want to try out. It is usually influenced from other types of cartoonists, if they are using a certain type of brush treatment or something, I might try to emulate it. I won’t do it well, but it will usually transform into something of my own.

ROOM: The colours in your work are beautiful. Are they all accomplished with Photoshop?

EC: Well, sort of, the colouring’s all done in Photoshop. Usually it’s all flat colours, laid down digitally under inks or pencils that I’ve scanned in. But I’ve also scanned in ink washes that I’ve done on illustration board. In Photoshop you can apply that as a layer over a colour and it helps make it look a little more organic. It’s still a computer colour but it gives it a bit of texture so that it’s not so dark and glaring.

ROOM: On your blog you have a project with period costumes you’ve illustrated. What are your benchmarks for period costumes?

EC: I think I have a book from the ’20s and one from the ’30s that has catalogue pages showing men’s and women’s fashions and stuff like that. Usually I will set something in that time period so I can use a certain fashion aesthetic.

ROOM: So, you might find a time period or a look first and then write your story?

EC: A character may occur to me if I see a costume or a set of clothes, and then with certain comics that I’ve done that take place in a 16th centurytype place, I’ll find paintings or sketches that I’ll apply to the comic. Sometimes catalogues and sometimes paintings.

ROOM: I read you only started making comics in 2010. What drew you to writing and illustrating web comics at that time? Were you writing before this?

EC: When I was younger I made up stories, like I’m sure everyone does, just for my own daydreaming. Then in high school I ran table-top role-playing games a lot, which was basically just exploring a different part of storytelling because I would do a lot of writing for them and run players through these stories and adapt and improvise based on what they did. I used to write short stories, like prose, but I never showed them to anybody. I’ve always been drawing and making up stories, but I guess I never had the confidence to do a comic. It seemed like way too much work for me and something I didn’t know the rules of. I just never did it until 2010. I was friends with a lot of cartoonists because I went to school for animation and a lot of those people went on to become cartoonists and illustrators and started making comics. I was in a group with people making comics and I sort of drew one-off cartoons and things like that. Eventually I decided I wanted to do comics, but I needed to give myself a manageable assignment to do it, as opposed to launching into a huge story that I could never finish. When I was a kid, or in early high school, I did start drawing comics, but they lasted five pages. And they were terrible!

In 2010, I gave myself the assignment of drawing a comic in two weeks and I also decided that I was going to adapt a fairy tale so that I wouldn’t have to come up with an original concept or something like that. Once I finished it, I realized that I could actually finish something and had a finished product. It gave me the confidence to do it again.

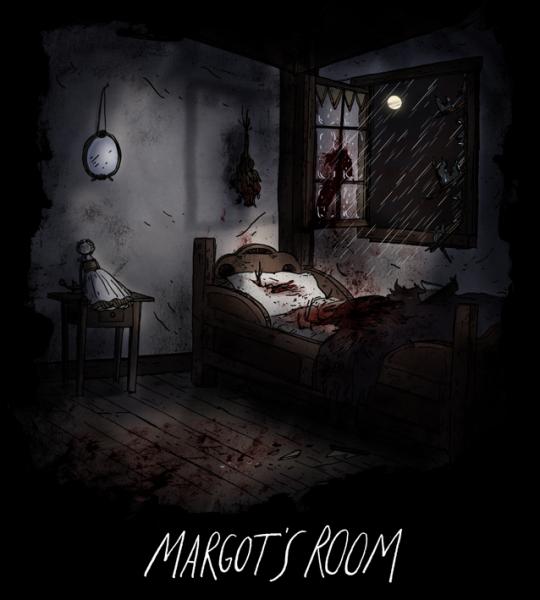

ROOM: In “Margot’s Room,” the reader can choose where to start or continue the story by clicking on a tableau of a child’s room where something terrible happened. Though the poem on the first page of the comic suggests an order, I didn’t realize  that until after. When you make your comics, are you thinking about how it will be adapted to the screen to create this non-linear effect?

that until after. When you make your comics, are you thinking about how it will be adapted to the screen to create this non-linear effect?

EC: Yes, and it’s funny that you mention “Margot’s Room” because originally it was going to be designed that you could click on any one [of the objects] and read them out of order or any order at all so that eventually the story would make sense as you read each one. That was part of how I designed it, and also that I would update it once a week. I put the poem in so people could figure it out because at first when people saw that comic they didn’t realize you were supposed to click on something, so I needed to put some breadcrumbs down. A line would appear week by week. After updating the page, another line in the poem would appear. It was a really fun one to do. With “Margot’s Room” it was very much part of that design that it had to be made for the screen, especially because I set it in the child’s room and you have to find the objects and click on them because I wanted to put the reader in a situation where they actually had to touch objects in a stranger’s room. I thought right away it creates a mild sense of unease or intrusion into the story. In that comic especially, I made sure the whole page was black around the story and the panels. It was very important to heighten the isolation of the main character and the shadowy dark tone of the story. I think with most of the web comics I do I keep the screen in mind and how people are going to be viewing it and I try to control it as much as possible. In those comics I don’t think I would transfer them to print because they were designed for the screen. Some of them could be transferred but others are specifically supposed to be read online.

ROOM: In your longer comics, the “click through” and “scroll through” from page to page feel very creepy. Some feel like cliffhangers, or like, as the reader/navigator, I’m pushing the narrative along more compared to flipping a print page. When you’re designing your art on the printed page, are you thinking of how the scroll will work?

EC: I don’t think of scrolling when I’m on the printed page. I think scrolling creates a sort of tension because you reveal things bit by bit as opposed to a page where in your peripheral vision you see the rest of the page. Originally when I first did scrolling I just did it because it was the easiest way to put things on the page. Initially, because I had never made print comics before, I wasn’t in the mindset of pages, so why not just throw things up in a big scroll? There were certain things I did with a scrolling effect, but in some cases it’s just the most convenient way.

ROOM: Your first book Through the Woods, a collection of short horror stories, was being published by Margaret K. McElderry Books in July 2014, and by Faber and Faber in the U.K. How did you find adapting your web comic to the print form? Will the comics in your book all be new?

EC: This book only has one web comic adapted in it, but it was still difficult because I had to adjust to the page. The web comic that’s in it was my first horror comic called “His Face All Red,” which is from 2010. It had to be adapted to print and I think it works pretty good, though I think it might be more successful on the screen, to be honest. Because page turns became really important. With horror comics or any sort of suspense comics, if you have a set up for a scare on the left-hand page and the scare itself on the right-hand page the effect would disappear immediately. That was kind of tough, but it was also kind of fun. It was fun to figure out how to pace information and reveal it to creep people out.

ROOM: Are the stories in this book based on fairy tales?

EC: They are all original, but influenced by fairy tales. There is one that has an interpretation of the Bluebeard fairy tale, which is my favourite type of fairy tale. And one is a Red Riding Hood story. The “Bluebeard” one was kind of funny because I wrote it and drew it and afterwards someone had messaged me if I had read Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber. Angela Carter was a writer, she passed away in the ’90s, I believe. She was a famous writer from England who did a lot of writing with fairy tales. She wrote this collection of fairy tales and one of them was about “Bluebeard.” It actually has a lot of symbols and things in common with my story. They aren’t the same, but there are certain things that we both put in.

ROOM: Any idea why both of you were picking up on similar things?

EC: They are completely different stories. There is just this one thing that is not in the original “Bluebeard” story, but is in my story where the main character gets a red ruby necklace and it is a pivotal point and a central symbol, and in Carter’s story the main character gets a red pearl and ruby necklace and it’s a central aspect of her story to the point where I wonder if people think I had read it before, but it was a very cool discovery because I am loving her work now.

ROOM: What do you like about fairy tales? Have you always been interested in them?

EC: It’s the first thing that really struck me as a little kid and the first thing that really scared me. I remember finding a copy of Grimm’s Fairy Tales and reading the original non-Disney fairy tales for the first time and just being shocked at all the stuff that was in it. So much murder and surreal malice in so many of them that was so unlike the other children’s books that I’d been given. It made much more of an impact on me. And I think that’s why I was so drawn to them because they evoke a visceral emotional reaction that I’m not even sure why it’s so unsettling. Fairy tales follow their own strange logic. I read them over and over and over, and I really liked finding different variations on a story’s theme, like how it changed in different regions and things like that. There is just so much to be done, and I know it’s not uncommon to do stuff with fairy tales.

ROOM: Horror, and the scariness of not knowing, is very present in your work. The endings of your work are often ambiguous. As readers, we have the pieces of the story, but no definite conclusion. What makes it more interesting to you as a writer  to have an open ending?

to have an open ending?

EC: I went through a seat change on this subject a few years ago. I used to hate ambiguous endings and things that were full of symbols that I couldn’t decipher. I really just disliked them. In my case, I felt stupid to be in the debt of those things. I thought people were just putting these symbols in to seem cool or artistic. Then, I played a game by a Belgian developer called The Path. It’s this weird video game with a Red Riding Hood homage where you have to select from one of seven sisters who span in age from six to sixteen or something like that, and you start out in the woods and you’re given a path to your grandmother’s house. The only words that come up on the screen are “Don’t Stray Off the Path.” You can walk all the way down the path and you’ll get to your grandmother’s house, everything’s fine and the game ends and you can start all over again with a new sister and play her. Or, you can walk off the path into the woods and you’ll find weird items in the woods and there is a wolf in the woods. The wolf takes various forms depending on which sister you’re playing. It is very ambiguous. I remember going online trying to figure it out. Then I finally read something from the developer and I discovered that they didn’t have a correct interpretation of what happened because there wasn’t one. They said this was the thing we wanted to make. Something told us to put this there and that there, but it is open to player interpretation. I had had such a strong emotional reaction to the things happening in the game, even if it didn’t have a story, and I think that really changed my thinking about it. You can still create something that is extremely worthwhile and extremely meaningful even if there is no puzzle to be solved. I think it also has to do with horror in general, too. You have to have ambiguity in horror, otherwise it’s really boring.

ROOM: Sometimes your imagination fills in the blanks of an ambiguous story …

EC: Yeah, there is a point in horror stories where you figure out how to defeat the evil thing, and once that happens it’s over. I really didn’t want that because in my work I want to evoke an emotional reaction in people or at least an unease … in a fun way. I don’t want to wrap things up because I’d rather have that unease linger.

ROOM: Themes of isolation and guilt appear throughout your work. What is it about those feelings that interests you?

EC: I was reading the Margaret Atwood book Survival, and she talks about the main themes in Canadian literature, and it was the same sort of thing: not feeling good enough, isolation, survival. I felt like, oh, maybe that’s what is influencing the stories I am writing. I always tell people that the main themes I see looking back on my work are envy and guilt, and guilt over that envy. I think that might be because it pairs well with horror. You can kill the werewolf with a silver bullet but you can’t kill your deep-seated resentment toward your child or your sibling. That is the emotional truth in the story.

ROOM: Would you say a lot of your stories are set in Canada?

EC: Some of my more recent ones, ones that aren’t out yet. I don’t say that they are in Canada, but I always imagined they were there. It’s very snowy. I’m working on a couple now that take place in southern Ontario. I recently moved back to southern Ontario, which is where I’m from.

ROOM: Home of the Canadian Gothic!

EC: Exactly! The Southern Ontario Gothic. I didn’t realize that term existed and then I read about it and I really liked it. Otherwise, I think because my stories are influenced by German fairy tales, I’ve set them in a sort of German-inspired area. I think they are set somewhere in a made-up forest.

ROOM: In this issue we are exploring the idea of geek girls in popular culture. I noticed that you’ve done a fair bit of fan art, particularly thinking of your Dune series. What do you think about the issue of women interested in so-called geek culture being called “fake”?

EC: I don’t think I’ve ever really experienced being called a fake geek, but I don’t participate in broader fandom culture. I’m not involved with message boards or things like that. I have so far never done cosplay at a convention. I do make fan art and play video games and tweet about it a lot. I have friends who have experienced it because I do have a lot of friends who are involved with video games. I hear reports of them being spoken down to or treated like they don’t actually play the game. It’s definitely a huge thing. I feel like I’m too much of a recluse to get the full brunt of it. Maybe it’s because I draw Dune fan art that nobody has ever questioned my Dune cred.

ROOM: Ok, final question. What’s next for you and your work?

EC: I have a short twenty-two page comic coming out in November, which is one of the ones taking place in southern Ontario. It is being published by Youth in Decline out of San Francisco and is part of the series Frontier #6. It will be a horror comic. Then after that, I will be illustrating an adaptation of the book Speak by Laurie Halse Anderson from the late 1990s about a thirteenyear-old girl dealing with the post-traumatic stress of a rape. It’s a huge book in the U.S.A., and I think it’s banned in a few states. Laurie will be adapting it and I’ll be illustrating it. In between doing all this stuff, I think I’ll be slacking off and doing more web comics. Web comics is basically making more work for myself, but every so often I have to take a break from the work and update it. I have a friend who calls it a working vacation because you take time away and do something fun that you can control. The great thing about web comics is you are your own publisher, and in my case my own artist and writer.