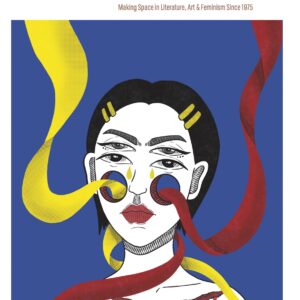

The 2021 Cover Art Contest Judge is renowned artist and illustrator Chief Lady Bird. Chief Lady Bird is an Anishinaabe artist from Rama First Nation. She graduated from OCADU in 2015 with a BFA in Drawing and Painting with a minor in Indigenous Visual Culture. Chief Lady Bird’s art practice is continuously shapeshifting, and is always heavily influenced by her passion for empowering and uplifting Indigenous folks through the subversion of colonial narratives. She hopes that her images can be a catalyst for reimagining our relationship with the land, each other, and ourselves.

You can read our conversation below to find out what guides her creative practice, and more. This year’s cover art contest is open until January 15th, 2021.

[This interview was conducted via email.]

—-

ROOM: Can you share a bit about your creative process and what drew you to pursuing your BFA at OCAD? As well, do you have any advice for young folks who are aspiring artists?

CHIEF LADY BIRD: I was drawn toward pursuing my BFA because I am inherently creative, and knew from a young age that I would be unhappy if I spent my life working in an office or something like that. I dreamed of being able to make a living off my art and attending OCADU was a beneficial first step as I explored what it meant to be an Indigenous artist. Being able to explore different mediums was especially beneficial to me as I found my voice and when I started my career I ended up finding a passion for digital art, which has blossomed into many awesome creative endeavours. My creative process is quite different for each project. For instance, when I am illustrating children’s books, I study different forms of video games and animated media; I also watch the children around me closely- how they move, emote and interact with the world around them.

ROOM: As Indigenous people, kinship and community are traditionally significant driving forces for the ways in which we navigate the world. I’m wondering what role community and kinship play in your artistic practice? Do you feel any responsibility to your community and Indigneous people more broadly as a well known artist and creative?

CLB: Kinship and community are absolutely driving forces in my career. I recognize that there is a responsibility to not perpetuate harm when creating and sharing artwork at an international level- especially if spotlighting controversial or a contentious topics. Artists often tell hard truths, especially when confronting social issues. And when you add an Indigenous lens, the complexities only deepen. So for me, I am always considering who may be impacted by the work I’m making, who will or won’t feel represented by it. I am also conscious of the folks who will be viewing my work who aren’t the target audience and consider how this may shift the perception of the stories and concepts I’m sharing. Because of all of this, I strive to be accountable by engaging with questions or criticisms about my work, and learning from the conversations that happen.

ROOM: One way that I have witnessed your artwork uplift and contribute positively to a broad sense of community and Indigenous advocacy, is through your label artwork for Great Lakes Brewery. You designed a beautiful digital image that features a blackbird and stars for an Indigenous Brew Crew initiative meant to raise awareness and funds for Indigenous women’s organizations in Ontario. This design has received positive feedback, but some people have questioned why you, an Indigenous person, would participate in a project that includes alcohol. I really appreciate and respect the way that you transformed this artwork into a conversation on normalizing, destigmatizing and challenging the shame that is too often placed onto Indigenous people who struggle with addiction and substance use as illustrated in this CBC Article. This discussion reminds me a lot of the term “sacred party auntie” which Auntie Edzi’u often speaks to, challenging stereotypes of the Indigenous “drunk”. I’m wondering if you’d like to add anything to this conversation, or share on the topic of destigmatizing substance use as Indigneous people, and how artwork can be used as a political tool for change.

CLB: Thank you for your kind words and acknowledgement of this project. If I’m being honest, it wasn’t easy at the time dealing with the amount of attention this project received, and this is actually the contentious issue I was thinking of when answering the previous question. But I tried my hardest to listen and learn from these conversations. Everyone who presented their opinion, regardless of which side of the issue they stand on, had a right to feel the way they did. I understand why folks are hesitant to accept Indigenous representation in the alcohol industry because of the harmful stereotypes we face. Racists will use alcoholism as a weapon to demoralize and devalue the work we do within our communities and because we face these stereotypes, the hesitancy to accept a project like this makes a lot of sense to me because I know many of us want to collectively work toward positive representation. However… I think that positive representation can also grow from conversations that are difficult to have. And as an artist I am not one to shy away from talking about difficult things and challenging perceptions or the status quo. I also always like to challenge colonial views and expectations of indigenous folks, and this one in particular has the potential to be truly transformative. I don’t like feeling that we are trapped in boxes of how we’re expected to be, for example how we are often expected to be palatable or be the “good Indian” in order to be respected. And the reality of it is that some of us drink. Some of us party. Some of us go to ceremonies. Some of us are language learners. Some of us are raising children. Some of us do all of the above, in moderation, and in balance. And the other side of the coin is that some people haven’t achieved balance with this. Some people experience substance abuse. And I personally don’t believe that anyone in our community should be excluded from ceremony or cultural activities or essentially exiled because they’re struggling. In fact I believe that folks who are struggling with substance-abuse should be given the most access to ceremony and healing and love. One of the biggest issues with my beer can design was that the black bird in question was misconstrued as a Thunderbird and I am OK with us because I think even though I didn’t intentionally create a Thunderbird (my Thunderbird design is very very different from the way that I illustrated this bird). But I’m OK with this because the Thunderbird brings healing and helps everything in nature grow and I think that the conversations that happened around this issue are going to encourage growth and also encourage folks to really think about how they interact with substance-abuse issues and addiction. And our community needs to collectively consider how we have isolated folks within our own communities by trying to be morally superior to one another and we need to reconsider our teachings and relearn how to love.

ROOM: Some of my favourite work of yours focuses on celebrating the erotic, and highlights Indigneous sexuality and love for the body in all forms. You have some beautiful self-portraits that really celebrate your love for yourself and model a sensual intimacy with the self that I adore. Specifically, a favourite of mine is your piece “Love Your Indigenous Foods Love Your Indigenous Lands Love Your Indigneous Self”, which speaks to food sovereignty and body sovereignty through a self portrait. I’m wondering if you have any specific pieces that you’ve created which you’d consider favourites?

CLB: The piece that you just mentioned is actually one of my favourite pieces that explores sexuality and self-love because it encompasses different layers of what it means to love oneself unconditionally while also understanding the ways colonization has fractured our connection to ourselves and the land through forced removal. It’s an acknowledgement of the radical ways Indigenous femmes access connection at a cosmological level by enjoying the sensuality of life. I have another piece too, a digital illustration, of a woman with “Ever Sacred, You” tattooed on her ass, about how modesty and sacredness are not mutually exclusive. I wanted this piece to speak to the folks who shame those of us who openly and willingly share our sexuality and our bodies; I wanted to challenge the perception that I am not sacred if I am not modest. This piece also interrogates puritanism, which a lot of my work does (including the beer can).

—–