Tansi, hello! Welcome to our online celebration of Black History Month with the Indigenous Brilliance Collective and Room Magazine. For the month of February, we will be sharing weekly content on the @indigenousbrilliance Instagram page, as well as over here on the Room website. This month we will explore different media recommendations from Patricia Massy of Massy Books, share interviews and content from featured Black and Black/Afro-Indigenous creatives, as well as dive into thought provoking questions, all related to the topic of Black/Afro-Indigeneity on Turtle Island.

For this first week, we would like to highlight some collective thoughts sparked by the question, “What does Black-Indigenous/Afro-Indigenous mean?” We will also share part of our interview with Black-Indigenous creative Cheyenne Wyzzard-Jones, who is our feature interview for Room issue 44.3 Indigenous Brilliance. We hope you enjoy it!

So, what is Black-Indigenous/Afro-Indigenous? This is a foundational question that can help us understand the shared histories of Black and Indigenous peoples, as well as build a better understanding of the many folks, like myself, who exist as both Black and Indigenous. This is all important learning in helping us establish a stronger sense of solidarity between Black and Indigenous communities, and allow us to acknowledge the unique and often underrepresented subject position of Black-Indigenous/Afro-Indigenous folks.

Black-Indigenous and Afro-Indigenous are both terms used to describe anyone with mixed Black, African, and Indigenous ancestry. Black/Afro-Indigeneity is a varying identity which includes Blackness and Indigeneity from multiple continents, nations, and lineages. There is not one simple definition for this term, which means that learning to understand this identity isn’t a simple endeavour.

I’d like to personally note that the experience of Black/Afro-Indigeneity on Turtle Island is much different than that of folks living on different continents, and we are currently only exploring experiences of folks living on Turtle Island for our posts this month.

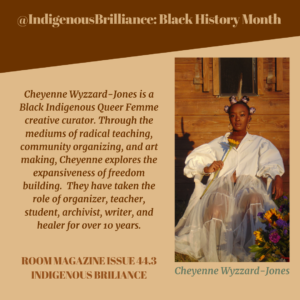

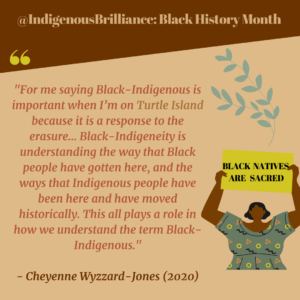

For Room issue 44.3 Indigenous Brilliance, I had the pleasure of interviewing Cheyenne Wyzzard-Jones, a Black-Indigenous Queer Femme creative curator. Cheyenne shared many insights into their identity and experience as a Black-Indigenous person. Cheyenne poignantly stated that “where solidarity lies is understanding that Black-Indigenous Nations exist.” This quote speaks to the erasure of Black-Indigeneity that is so commonly experienced on Turtle Island, and the importance of Black/Afro-Indigenous folks being uplifted by Black and Indigenous community. Indeed, we can look to these folks for leadership in building solidarity within our movements.

For myself, I have long felt that part of my identity must be compromised in nearly every space I find myself in. It seems that it is often too difficult for people to understand me as both Black and Indigenous simultaneously, especially in cultural or politically charged spaces. It is as though I am always too much or not enough, so I find myself carefully choosing to share only the parts of myself that might be held and respected as sacred while I navigate the world as a Black-Indigenous person. I imagine that this must be a common experience for many mixed-race people, and is a sentiment in which I find comfort in solidarity.

I believe that Black-Indigenous people have unique worldviews and understandings of multiple community spaces as both insider and outsider. Depending on multiple factors, I can feel included or excluded from certain Black or Indigenous spaces. Depending on what I’m wearing, how I speak, where I am, and who I’m with, folks might perceive me as either Black, Indigenous, both, or something else entirely. But at the end of the day, I am constantly accounting for how people perceive me, and what assumptions they may have about me accessing certain cultural spaces because of the way I look.

In The Souls of Black Folk, W.E.B DuBois explains the idea of “double consciousness” which suggests that Black people often experience a “two-ness” of sorts, a result of our racialized oppression and the white gaze we experience in a settler colonial state. As a Black-Indigenous person, I find that on top of the double consciousness I experience as a Black person under the white gaze, I also experience a similar “gaze” from many Indigenous folks, particularly when I am accessing cultural spaces. This is all to say that Black/Afro-Indigenous folks have a specific experience of Blackness and Indigeneity that consistently co-exist, but are not often acknowledged or understood holistically.

I echo the hopes of Cheyenne, that more BIPOC will acknowledge and look to Black-Indigenous folks for leadership in our fight for sovereignty, and to build camaraderie in our collective efforts for liberation. As Cheyenne notes, “Black-Indigenous are the start to Black and Indigenous solidarity for me because you have to acknowledge the Blackness that co-exists within Indigeneity inherently, rather than looking at it as two separate experiences coming together.”

When beginning our work on Room Issue 44.3 Indigenous Brilliance, our editorial team asked ourselves why it was important to include Black-Indigenous, Afro-Indigenous, and Black peoples in the work that we do. Answering this question has been an unfolding process of learning and understanding terminology, histories, perspectives, and realities. Throughout this process, we have engaged in many significant conversations, including one between Indigenous Brilliance Collective member and owner of Massy Books, Patricia Massy, and Parker Johnson. Parker is a Continuing Studies faculty member at Simon Fraser University, a group facilitator, mediator, intercultural educator and organizational change specialist who is committed to building just, equitable, diverse, and inclusive organizations.

When beginning our work on Room Issue 44.3 Indigenous Brilliance, our editorial team asked ourselves why it was important to include Black-Indigenous, Afro-Indigenous, and Black peoples in the work that we do. Answering this question has been an unfolding process of learning and understanding terminology, histories, perspectives, and realities. Throughout this process, we have engaged in many significant conversations, including one between Indigenous Brilliance Collective member and owner of Massy Books, Patricia Massy, and Parker Johnson. Parker is a Continuing Studies faculty member at Simon Fraser University, a group facilitator, mediator, intercultural educator and organizational change specialist who is committed to building just, equitable, diverse, and inclusive organizations.

As we were creating the call for submissions to our issue, Patricia reached out to Parker in an email, asking him about his opinion on using Indigenous terminology without excluding Indigenous folks from around the globe, specifically mentioning our desire to include Afro-Indigenous/Black Indigenous artists and writers. Parker replied,

“You ask an important and difficult question. If the concern is inclusion of Black Indigenous peoples relates to Americas, Caribbean and Africa, which are informed by interwoven histories of European colonialism, genocide, enslavement, subjugation, resistance, sovereignty and liberation… If your intention is to invite the Indigenous peoples of what is called Latin America and the Caribbean or what is colonially known as the Americas and Caribbean. I am overjoyed to see the effort.”

This lead Patricia to the conclusion that “if we are going to acknowledge there are mixed Indigenous folks from around the world, we first need to define ‘Indigenous,’ as the term is often used to refer broadly to peoples of long settlement and connection to specific lands who have been adversely affected by incursions by industrial economies, displacement, and settlement of their traditional territories by others.”

This brief dialogue allowed us to form our call for submissions to the our Indigenous Brilliance issue, and continues to inform our ongoing discussions as we put the issue together and read all of the great submissions. You can read more about our call, which closed on January 31, and our round-table interview with the Indigenous Brilliance editors.

This brief dialogue allowed us to form our call for submissions to the our Indigenous Brilliance issue, and continues to inform our ongoing discussions as we put the issue together and read all of the great submissions. You can read more about our call, which closed on January 31, and our round-table interview with the Indigenous Brilliance editors.

We also intend on including Black-Indigenous and Afro-Indigenous folks in all the work we do moving forward. As noted in our call for submissions, we want to acknowledge that many Indigenous communities, establishments, and organizations willingly, or unwillingly, perpetuate anti-Black violence and discrimination. We intend to openly speak to this reality as an attempt to dismantle anti-Blackness that may be experienced by Black-Indigenous, Afro-Indigenous, and Black folks in relationship with Room or Indigenous Brilliance.

We hope that through our work this month, we can embody a commitment to dismantling anti-Blackness within our own community, and that we can show up for Black-Indigenous and Afro-Indigenous people in the work that we do. We want to share Indigenous Brilliance that includes folks who are Indigenous to all areas of the globe, specifically challenging the anti-Blackness that too often inhibits Black-Indigenous and Afro-Indigenous folks from safely and comfortably accessing Indigenous centred spaces.

So, what is Black/Afro-Indigeneity? It is a varying identity which includes Blackness and Indigeneity from multiple continents, nations, and lineages. There is not one simple definition for this term, which means that learning to understand this identity isn’t a simple endeavour. We aim to spark a curiosity and interest in learning more about these identities through our Black History Month posts and our 44.3 Indigenous Brilliance issue.

It is our hope that we all can commit to holding space for the celebration, liberation, and uplifting of Black/Afro-Indigenous peoples, as well as all BIPOC in solidarity with our many communities.

On that note, we will see you next week for some more exploration, learning, and celebration of Black History Month with Indigenous Brilliance and Room.