Shades of Sadness | 27.1

2004

Digital only; out of stock in print.

I was hesitant to declare that the theme of the first issue of 2004 is sadness. My trepidation was purely the result of concern that Room of One’s Own would be labelled depressing. And, such a label is not attractive. However, the stories and poems contained herein could not be re-packaged into what I thought was a more savoury theme. And so, the theme remained—along with my wish to avoid more thought on this topic. I have learned that when I’m feeling blue the best remedy is to briefly acknowledge the sadness but never dwell on it. I move right along to a new exciting task or distraction. The whole of North American society seems based on this continual quest for some distraction (think of consumerism as an extreme example).

Not so in all cultures. Not so in Latin American culture. Let me give you an example. A few years ago I attended a Mercedes Sosa concert in Vancouver. This concert was populated almost exclusively with Latino expats, most of them political exiles. When Sosa sang her remake of Chilean-songstress Violetta Parra’s Gracias A La Vida I noticed that tears were streaming down the faces of people in the audience. Rather than avoiding sadness, in this venue sadness was public. To this day, I’m not sure what it was that spurred this collective grief, but for me it was listening to the lyrics of that powerful song, in which the songstress thanks life for the gift of sadness, which, after all, allows her to understand her neighbour’s humanity.

Likewise, the stories and poetry contained in this issue elegantly tell of moments of sadness, without histrionics or exaggeration. But like myself, not all of the characters in these stories want to focus on sadness. The main character in Lynn Hamilton’s “I Won’t Be Here” is in denial of her grief, so much so that her relationship with her young son is affected. Now she has become one of the main causes of her son’s pain. It is only when she sees her pain as her son does that she is able to move forward. Similarly, in Mary Patrick’s “Goody Grief,” the main character is attempting to put behind her the grief over the death of her spouse but her whiny cat won’t let her. The cat voices his pain with increasing intensity until he is impossible to ignore.

The main character in Dora Dueck’s “This Postponement” is in a crisis and experiences almost panicked grief because of a recent diagnosis that she has cancer. She tries to shield her husband from the sadness that she knows will engulf him once she shares her news. Although her actions seem illogical, the character wants to strengthen herself before her sadness becomes public, unavoidable, and shared among her family. Perhaps she is afraid that her pain will increase as a result of watching her loved ones suffer. In “A Call for Extras,” the main character, Sophie, is already suffering from the grief of a separation and the stress of a transition to new motherhood when her mother becomes gravely ill. This illness serves to better prioritize what is important in Sophie’s life and enables her to appreciate the hope that her new daughter provides. By contrast, Dorothy Field writes of her regret that she was unable to “build a bridge” to connect with her father before he died. Everyday things—a bureau, crossword puzzles—make her think of him and lament lost opportunities. Even more poignant, because it is not the natural order of these things, is Stephanie Dickinson’s poem “In the Recluse Woods,” in which parents mourn the death of their three children. A girl who visits their shut-in farm to deliver supplies notes of the mother, “her face is three funerals” and the girl dreams of smallpox, “the speckled monster” that smells “bitter as curtain dust.” In Dickinson’s world, death, and the tiny voices of the dead, are startling in how effectively they evoke deep sadness.

What do you do when sadness exceeds grief? In the story “A Mediterranean Life,” a woman suffers from decades of watching the pain that her daughter and husband endure because of depression. Not only does this story delineate the difference between a clinical illness and sadness, it also shows the resilience and strength of character of a woman who is holding her family together. Laura Krughoff’s “Acts of Kindness” also revolves around a woman who is the lynchpin in a family that has been struggling. Even when this woman faces a wrenching decision that forces her’to choose between need and morals, she is able to put her own concerns aside to help another.

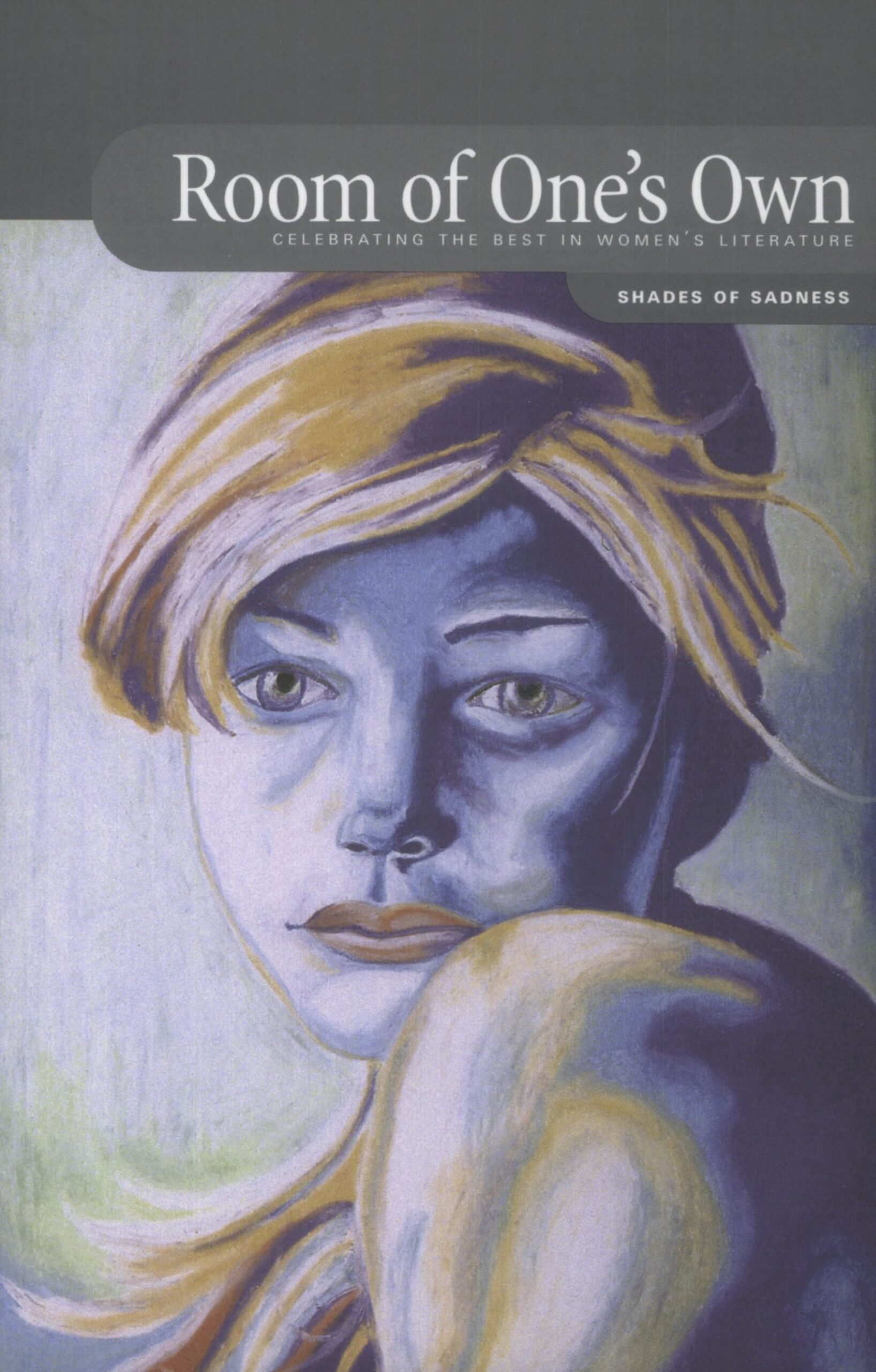

It is such acts of kindness that are common among the stories contained in this issue—and in the art on the cover. Artist Gigi Hoeller seeks to connect deeply with emotion and certainly the woman she has created exudes sadness. But Hoeller also has a more compassionate purpose—she invites viewers into her paintings to escape stress and find serenity. All of the characters in and on this issue, regardless of the gravity of the pain they suffer and how justified their pain may be, have moments where they are able to look outside their pain and into the experiences of those around them.

$10.00

Additional information

| Delivery | Canada, USA, International, Digital |

|---|

In this issue: Virginia Aulin, Rosmarie Bronnimann, Trisha Cull, Stephanie Dickinson, Dora Dueck, Julie R. Enszer, Dorothy Field, Barbara Fraser, Alison Frost, Rachel Hall, Lynn Hamilton, Gigi Hoeller, Laura Krughoff, Laura Edna Lacey, Aimée Lajeunesse, Mary Patrick, Monica Woelfel, Lindsay Zier-Vogel