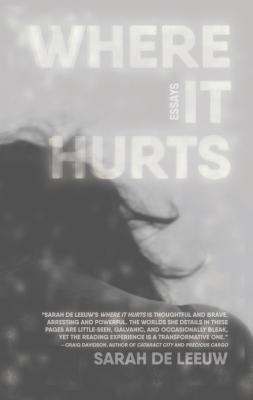

The essays in Where It Hurts are deeply felt, original, and a moving requiem for lives extinguished too early to have left a trace. De Leeuw writes with love and conviction while also asking important questions of the reader: how do we live with the empty spaces death makes?

In the title essay of Sarah de Leeuw’s compelling new collection, Where it Hurts, a young mother new to a northern British Columbia town is nervous when a stranger asks to hold her baby. Too polite to say no, the young mother watches as the woman—whose name is Cowboy— grabs the baby and bounces her up in the air. For a moment it seems the woman will drop the infant. But, as it turns out, the woman is imperiled herself. In a few months, she will appear in the newspaper, found murdered on the side of The Highway of Tears.

Such fleeting, haunted connections, and a tone of aching love, run through the essays in Where it Hurts, many of which share the theme of disappeared women. These women include Cowboy, along with nameless vanquished girls—the faces on the backs of milk cartons—who were abducted, murdered, or died young, in summertime teen prime. De Leeuw makes these lives visible through soaring lines that are poetic and visceral, like teenage girls “all lanky limbed in jeans a size too small, hair . . . shining elemental with peroxide gold.” Where statistics about human tragedies can leave one numb, de Leeuw’s luminous concrete description jolts with riveting clarity and empathy. It forces your attention on that hurt, and on the spaces and unanswered questions these women’s deaths leave behind.

Some of the women come from vanishing communities: old logging towns, truck stops at the top of the Stewart-Cassiar Highway—shuttered when the resources ran dry—and post-industrial northern townships, where, as she writes, a film festival comes by every two years. De Leeuw, a human geographer, poet and non-fiction writer, connects these dwindling towns to marginalized lives, subtly showing how remote geographies can make lives more prone to erasure. De Leeuw’s writing is a hedge against these women’s lives fading, combining images of corporeal decay (“plastic bags, snagged on brambles and translucent as lungs”) with the organic and beautiful (“soft mauve lilac flowers”). While elegiac, de Leeuw’s pencil has a fiery point and her writing is a revocation of silence. “Inquiries result in findings,” she writes, “and findings can be documented and published and circulated so people pay attention and search for solutions.”

The essays in Where It Hurts are deeply felt, original, and a moving requiem for lives extinguished too early to have left a trace. De Leeuw writes with love and conviction while also asking important questions of the reader: how do we live with the empty spaces death makes? And as the living, how do we honour, and fight for, the women these empty spaces represent?