Tansi, hello! Welcome to week two of our online celebration of Black History Month with the Indigenous Brilliance Collective and Room Magazine. For the month of February, we will be sharing weekly content on the @indigenousbrilliance Instagram page, as well as over here on the Room website. This month we will explore different media recommendations from Patricia Massy of Massy Books, share interviews and content from featured Black and Black/Afro-Indigenous creatives, as well as dive into thought provoking questions, all related to the topic of Black/Afro-Indigeneity on Turtle Island.

This week, we will be focusing on some local history and geographical discourse relating to the community of Hogan’s Alley, on the unceded and unsurrendered territories of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh peoples. We will also be discussing an award-winning short film titled Where We Meet by Lexi Mellish-Mingo and Karmella Cen Benedito De Barros. We hope you enjoy it!

What is Hogan’s Alley?

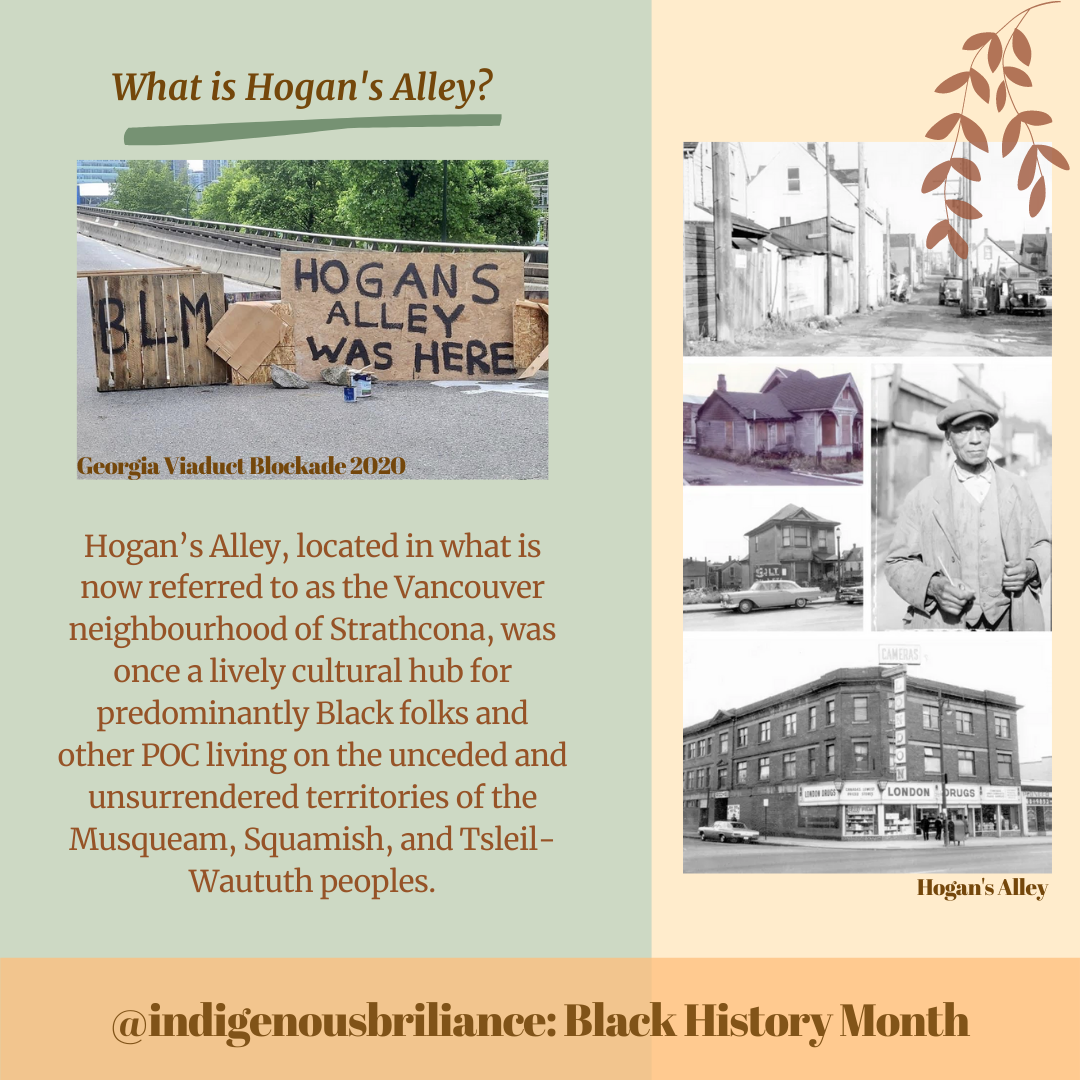

Hogan’s Alley, located in what is now referred to as the neighbourhood of Strathcona, was once a lively cultural hub for predominantly Black folks and other people of colour living on the unceded and unsurrendered territories of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh peoples. According to the Vancouver Heritage Foundation, Hogan’s Alley was established in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s as the first Black immigrants arrived on the West Coast, initially settling on Salt Spring and Vancouver Island. A community slowly formed in the east side neighbourhood of Strathcona, including folks of Italian, Chinese, Asian, Black, Indigenous and other minority groups. This working-class neighbourhood is said to have been a community core, drawing in Black homesteaders, emancipated slaves, railroad porters and travelling entertainers from all over Turtle Island.

As noted on (Blackstrathcona.com), the narrow alleyway running “from Main to Jackson between Union and Prior” was referred to as Hogan’s Alley. Notably, about 300 Black folks lived in and around this neighbourhood, making it a community hub throughout much of the 1900’s.

The City of Vancouver developed as the years passed, and eventually an urban renewal plan was established that focused on cleaning up the Hogan’s Alley and the Strathcona area. In 1967, the City proposed a plan to build a freeway through Strathcona, Chinatown, and Gastown, which was met with resistance and protest from local residents. The uniting of the surrounding neighbourhoods resulted in success. In 1972, the City abandoned the policy for urban renewal, but approved the plans to build the Georgia Viaduct, which would destroy two blocks of Hogan’s Alley and displace the Black community.

The legacy of Hogan’s Alley was not lost with the second construction of the Georgia Viaduct and the displacement of Vancouver’s former Black community. Despite the small and scattered Black population in the Metro Vancouver area, a number of groups have continued to commemorate the former cultural hub over the last two decades. What was once home to predominantly, but not exclusively, Black folks holds a history of action that has been intentionally erased. On the same ground, we witness history in the making, as the retelling of history informs the place-making of the future.

In 2003, Hogan’s Alley Memorial Project (HAMP) was founded, which commemorated the history of what we now refer to as Hogan’s Alley. In 2007, the organization and artist Lauren Marsden raised public awareness of the former community through a floral installation alongside the green space beside the Georgia viaduct. It read “Welcome to Hogan’s Alley.” The community was never fully forgotten, and has taken consistent effort to have the City formally acknowledge it.

The early development of HAMP prompted the efforts of Hogan’s Alley Working Group (HAWG) which worked with the city to start a dialogue regarding the history and future of Vancouver’s Black community. Hogan’s Alley Society (HAS) carries the legacies of HAWG and Hogan’s Alley Land Trust (HAT) by working with the city to carry forward a community land trust and cultural centre.

Today, Hogan’s Alley Society focuses their efforts by partnering with Portland Housing Society to support the tenants of Norah Hendrix Place (NHP), located along the Georgia viaduct, The Norah Hendrix Place modular housing project acknowledges the displacement of the former Black population, while functioning as a centre to rebuild the community of Black and Indigenous residents of the Downtown Eastside (DTES).

Outside of Hogan’s Alley Society are a number of smaller organizations that are working across the metro Vancouver area to address the erasure of Black history, develop a network of support for Black people, and create dialogue around mental health and anti-Blackness in the City. Groups such as the Emergency Black Community COVID-19 support fund, Vancouver Black Therapy and Advocacy fund, Black Lives Matter Vancouver, and many others keep the flow of communication and support maintained during a global pandemic.

Despite COVID-19, the unjust murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Regis Korchinski-Paquet, Ahmaud Arbery, Philandro Castille, and numerous others, brought together thousands of people to the Vancouver Art Gallery on May 31st 2020. With such a huge response to the large-scale injustices of police brutality in Canada and the US, came a mainstream acknowledgement of the racial injustice utilized by law enforcement here in Vancouver.

From June 13th-15th, 2020, Black and Indigenous youth and organizers blocked off the Georgia Viaduct, calling forth the City and the broader public to see the global Black Lives Matter movement in a local context. This particular movement drew attention to Black Trans Lives, and the politics of whose bodies matter and emphasized the remembering of those forgotten, including the former Black cultural hub in Vancouver.

The blockade commemorated the former community that was destroyed as a product of the City’s anti-Black agenda, calling forth the city to address Black Lives Matter Vancouver’s List of Demands. Some of the demands included were the defunding of the Vancouver Police Department and redistribution of funds to community safety initiatives, committing to ending the police and prison systems, taking police out of schools, addressing the displacement of Hogan’s Alley, and following through with a community Land Trust.

The reclamation of Hogan’s Alley brought together movement leaders from across Vancouver to actively address the impacts of anti-Black and anti-Indigenous racism in Vancouver throughout history. The city has yet to complete the C.R.A.B park longhouse, which has been a demand from Vancouver First Nations groups for the last two decades. Despite the growing awareness of the former community, there is no justice on stolen land.

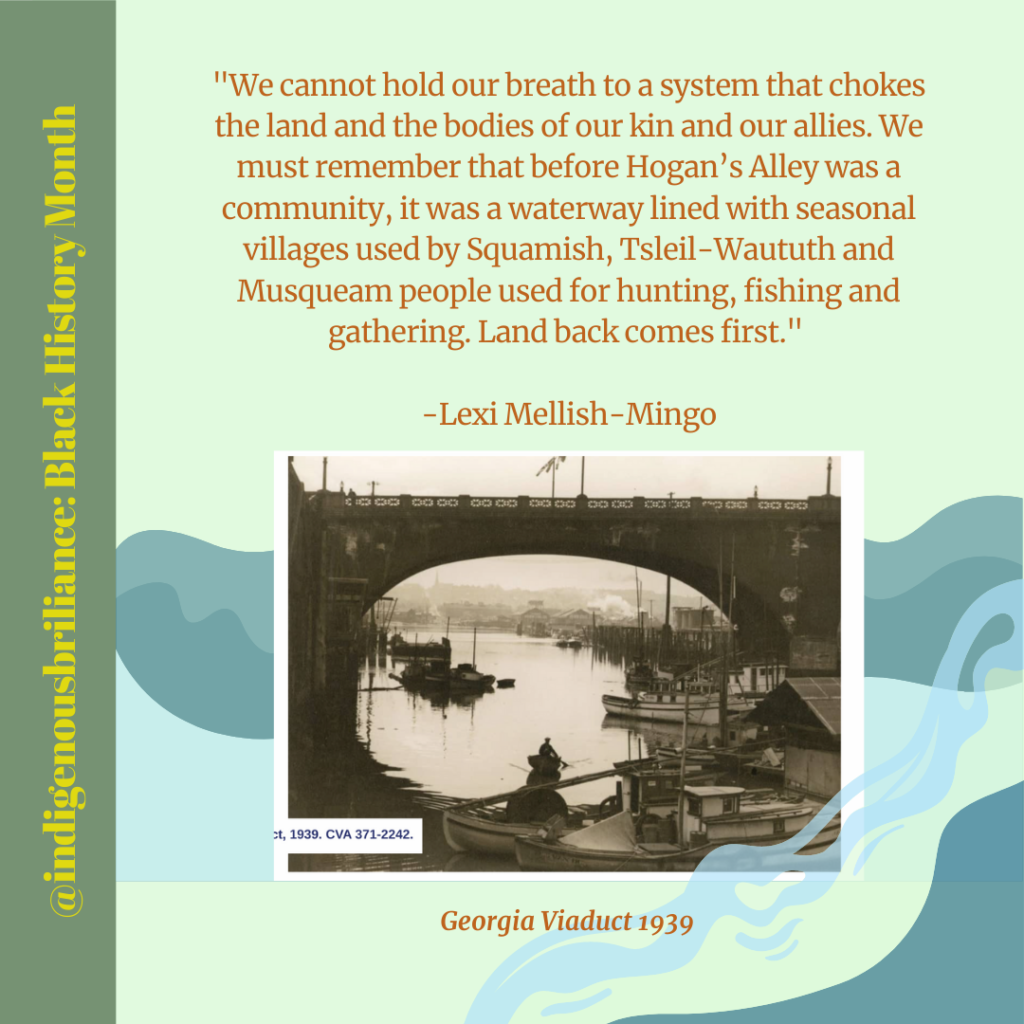

We cannot hold our breath to a system that chokes the land and the bodies of our kin and our allies. We must remember that before Hogan’s Alley was a community, it was a waterway lined with seasonal villages used by Squamish, Tsleil-Waututh and Musqueam people used for hunting, fishing and gathering. Land Back comes first.

Why is it important that we tend to the budding seeds of Black community?

With a Black population of 1%, we challenge distance and displacement by continuing to grow community beyond land-based margins. Sharing wealth, knowledge and privilege is how many of our ancestors survived and thrived. We created an ecosystem where coming together was vitality. These roots are the fruit of our future.

May these fruits welcome and honour diversity, and betray all tools of the oppressors; let them listen and hold up the voices of the host nations by showing up and offering support and care. May the fruits of the future hold all the flavours of all the years before in celebration.

Black community has never held one name or shade. It exists and it doesn’t. It is, and has been a tool for survival. It can turn an apocalypse into a future.

As a collective, we believe that it is important to acknowledge the histories and realities that co-exist amongst us through the territory we occupy and exist with. It is a crucial step in our decolonial practice to acknowledge that we live and work on unceded and unsurrendered territory of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh peoples. But, as our collective member jaye simpson reminds us, “it is also important to name the people who have been displaced on these territories, including the Black community of Hogan’s Alley, the ongoing gentrification of Chinatown, the destruction of Japantown, BC’s history of Japanese internment and, the Komagata Maru incident in the Burrard Inlet.”

We call these histories in, as a way to acknowledge all those who have experienced displacement and trauma at the hands of settler colonialism. This is one way that we work to build solidarity and resistance to the continued colonization taking place on this land. We hope that this brief introduction to the history of Hogan’s Alley will spark a curiosity for you to learn more about the history of the land that you live on. It is our intention to remind you that there is always work to be done in learning the history that lives in the land around us, and that many communities and cultures have been intentionally erased.

Hogan’s Alley is just one example of anti-Black erasure that has displaced an entire community in the Vancouver area. There is much work to be done in re-establishing a Black community hub in the Strathcona area, and we hope that you will join us in actively combating anti-Black racism, beginning with confronting the histories of erasure and racism that have taken place on the land you live.

Join us for the online screening of Where We Meet created by myself and Lexi Mellish-Mingo. Check out the short doc Secret Vancouver: Return to Hogan’s Alley by Ruby Smith Diaz, wander through the streets of Hogan’s Alley with this interactive map on Black Strathcona’s website, and keep an eye out for Chelene Knight’s upcoming book Junie, a novel set in Vancouver’s Hogan’s Alley!

Until next time, thanks for tuning in for Indigenous Brilliance and Room Magazine’s celebration of Black History Month!