This Black Futures Month & Black History Month, we’re republishing brilliant works and conversations with Black organizers, writers, and artists from Room‘s past issues, to live on our site in perpetuity.

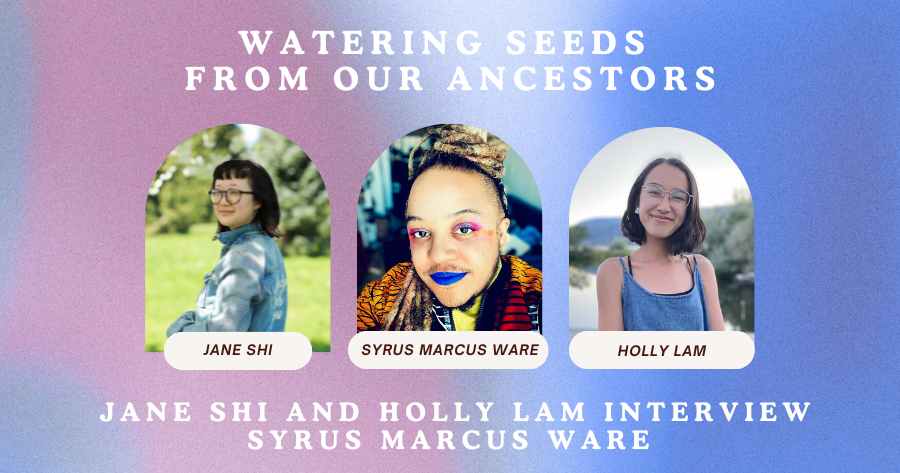

Today, we’re sitting with this conversation between Syrus Marcus Ware and Room editors Holly Lam and Jane Shi from Room 45.1 Ancestors.

Watering Seeds from Our Ancestors: An Interview with Syrus Marcus Ware

Where would we be in our thinking about ancestors and future ancestors without Syrus Marcus Ware? While meditating on our issue’s theme, Syrus’s work on imagining futures, speculative fiction as activism, and the role of art in building a better world as future ancestors came to us right away.

Syrus is a community activist, visual artist, and scholar who skillfully weaves together visions of abolition, disability justice, and resisting white supremacy through art. His installation Ancestors, Do You Read Us? (Dispatches From the Future) and related play Antarctica were commissioned by the Toronto Biennial of Art in 2019; both explore a future where disabled Black, Indigenous, and racialized people survive and thrive. Syrus is a core-team member of Black Lives Matter – Toronto and co-edited Until We Are Free: Reflections on Black Lives Matter in Canada. His project Activist Love Letters and activist portrait series personalize and uplift activist aesthetics for audiences, propelling us to take action and work together. Syrus spoke to us about the creative project of being an artist parent, the overlooked contributions of Philadelphia-based Black environmental justice group MOVE, and how systems are guaranteed to change and evolve.

ROOM: You recently defended “Irresistible Revolutions,” your dissertation on disability justice, abolition, and portraiture at the Faculty of Environmental Studies, York University. How has it been to finish this work (and in a pandemic)?

SYRUS MARCUS WARE: Oh, my goodness, what an adventure. I never would have thought that during the pandemic would be when I finished. PhD work can seem interminable. I was certainly not somebody who set out to be super productive during the pandemic, but I found that being at home and not travelling as much for my art practice allowed me to think back on my practice. Being so engaged in disability justice organizing in the community, I was able to thread that into my writing. “Irresistible Revolutions” draws on this idea, which is what my practice is trying to do: as Toni Cade Bambara suggested, make the revolution irresistible. I included portraits as an alternative dissertation, an exegesis of articles, and written content.

ROOM: Can you tell us a bit about what Toni Cade Bambara’s words “the role of the artist is to make the revolution irresistible” mean to you and how that idea manifests in your work?

SMW: Absolutely. Toni Cade Bambara said that the role of the artist from oppressed or marginalized communities is to make the revolution irresistible. She goes on to say that the very act of getting up and breathing can be an act of making the revolution irresistible. And she talks about the role of artists. I’ve been very interested in creating work that brings art and activism together. I’ve been both an artist and an activist for twenty-five years. My work has always been rooted in an activist aesthetic and consideration. When I went to art school in the nineties, I was strongly discouraged from doing the work I was doing, about the politics of my community and the realities of white supremacy and about gender, because I was told that it was too overt and too political. It really was quite an experience to go through that. So I’ve been very interested in this idea that my work can potentially be a catalyst that sparks people’s interest in supporting the lives of activists. Activist Love Letters and the activist portrait series are designed to get people to want to support and connect with activists, to ensure they thrive, not only survive. Also, through textile works like banner-making workshops, getting people learning the skills of organizing, so that they can get involved. Lastly, creating work that is rooted in the future, that inspires a sense of hope. Projects like Ancestors, Do You Read Us? (Dispatches from the Future), Emmett, and Antarctica are set in the future, and they suggest that Black and Indigenous and racialized people with disabilities survive. They literally come back in Ancestors, Do You Read Us? and say, here’s what you’ve got to do: overthrow capitalism, undo white supremacy, solve climate change, and we’re gonna make it. They lay out a blueprint for revolution. Toni Cade Bambara gives us so much to think of in that suggestion: what does it mean to make something irresistible? It makes it seem not only possible, but essential. That’s what I’m interested in sparking in people: the idea that they can’t wait to get to this new world we’re building toward.

ROOM: Yes! There’s such a scaffolding for joy in that work. Your portraits of activists are on very large canvases, created with graphite on paper. We typically think of our more recent ancestors through the medium of photographs, but these portraits offer a timelessness that cuts into white supremacist, colonial, and European traditions of visual art. Can you speak to how you approached this series and its medium?

SMW: I’ve been working on the activist portrait series since about 2014. I was so drawn to Emory Douglas’s practice and how he used very simple materials to convey complex messages. I thought, what could I do with just a pencil and paper, and inspire people to get involved in organizing? For this project, I photograph activists and ask them three questions: how they got involved in organizing; a speculative future question—if they could go to any time in human history and get involved in organizing, where would they go, when, and why; and a question about love. Their faces change and react in all these different ways in response. I pick photographs that are often of them in motion, in the middle of telling a story, so they seem alive. I draw them about twelve feet tall, so they’re larger than life, and the portraits become dedications for them, honouring their labour and organizing. Portraiture is so implicated in literally deciding who we consider valuable. When you think about who gets their portrait drawn, it’s not usually racialized people. It’s not usually working-class people, it’s not usually activists, it’s not usually disabled people. So flipping the script and saying, what would happen if we re-centre the frame around people at the margins? And what would happen if we tried to personalize the experience of being an activist: what would change in people’s interactions with the movement?

ROOM: One reason we were so excited to include you in this issue of Room is that you express so brilliantly the concept of speculative fiction as activism, as imagining another world. The introduction for Until We Are Free: Reflections on Black Lives Matter in Canada beautifully world-builds a future without police while being fundamentally impacted by climate catastrophe. It feels as though literature, activism, and science are alchemizing to give way for the book’s visionary history, action, and demands. How do you navigate the process of imagining a better future? How do you move from reckoning with the present and past into imagining alternatives?

SMW: It was such a joy to work on that book. That book was created by, for, and with community. We wanted to think about Sankofa, this idea of remembering our past in order to learn where to go in the future. We knew that archives do a terrible job at documenting what actually happened in any particular movement. We also knew that there had been so much written about Black Lives Matter by people outside of the movement. So we turned to community and we created this book. I had this suggestion, “What if we start and end the book with a speculative fiction excerpt?” It was a real joy to imagine this future where things were changing. By the end of the book in the epilogue, you find out that, in fact, things have transformed completely, and we have won. It was really beautiful to consider a future where Black lives mattered, and to prefigure a world where we survive. We write it into being through our practice. Walidah Imarisha talks about how all organizing is speculative fiction because it dares to dream that another world is possible. So it made sense in a book about organizing to include speculative fiction. The book is filled with our history, how BLM started in Canada, and it’s about all the real life experiences of activists: being disabled in the movement, being a mother in the movement, organizing in a digital age, talking about abolition in the movement, writing by prisoners, talking about Indigenous and Black solidarity, organizing in the North. All these things about people’s real life experience in this movement, archived while it’s actually happening. So it was a real joy, and we called it our ideal title, which was Until We Are Free, as a suggestion of where we’re headed.

ROOM: Your play Emmett that was featured in 21 Black Futures is so striking, not least because it is a beautifully staged production and theatres have been closed for over a year. What was it like to be part of that series, and how did your piece come about?

SMW: I had this phone call from Luke Reece when he was still with Obsidian, and he said, “Hey, Syrus, what do you think about writing a play about the future?” Antarctica had just performed at the biennial. I said, “I would love to write another play about the future. That’s right up my alley.” Then I found out about this expansive and incredible project and was just so honoured to have been asked: twenty-one Black creatives, twenty-one directors, twenty-one playwrights, twenty-one actors. Emmett is set in an indeterminate future, where the world is largely gripped by both climate change and viruses. I wanted to write a story about a disabled character who was perhaps, as the character Medgar says, the least likely to have survived an apocalypse—who survives. I want to write stories about the future where disabled people survive. I wanted to tell a queer love story. You don’t meet the titular character, Emmett, who Medgar is speaking to the whole time, because he’s deceased. But the play presupposes the perhaps radical idea that Medgar Evers and Emmett Till, key figures in the Black civil rights movement in the United States in the 1960s, are not only alive together in the future, but they’re in this queer love story. So that was my offering. I worked with my twin, who’s an entomologist and a scientist, Dr. Jessica Ware, and came to this proposal about an avian virus that wiped out all birds. So that added to Medgar’s isolation. It was an adventure to create this work. Tanisha Taitt was the most incredible director and brought this play to another level. The incredible actor Prince Amponsah brought such life to the character. The whole Obsidian team, the dramaturgs and the producers, were incredible, and the folks at CBC, so it was a dream come true to write this in the middle of a pandemic.

ROOM: When creating a narrative-based work like a play, where do usually begin the process? What comes to you first—concept or theme, setting, or characters?

SMW: With Antarctica, I had actually started to write it as a short story first. Then the biennial commissioned me to expand that into something else, and I decided to make it into a play, which is a different way of writing than prose, being so dialogue-focused. So I started with the overall concept and story—what would happen if the eleven people born in Antarctica were sent back there to set up future colonies?—and wrote that story, then adapted it into a play. For Emmett, because I knew it was going to be a play from the beginning, I sat down and wrote it. Emmett was a story that was already in me. I wrote it in one sitting, and then worked to edit and do the research for the scientific parts that I needed to fill in. But it just flowed out of me. It was really a dream state, imagining a future based on where we were in 2020 when I was writing. In 2005, I got to spend the day with Octavia Butler. I asked her how she was able to write what she wrote and predict the future in such an accurate way. She said that she just followed a trajectory: if we continue on the current trajectory that we’re on and don’t really change white supremacy and climate change, where might we end up? So I was channelling that spirit: what would happen if these viruses and pandemics, like COVID-19, just kept coming, fuelled by climate change, and what would it look like if things changed dramatically because of that?

ROOM: Who is part of your artistic lineages? Are there works or projects—books, stories, films, plays—that engage in, or artists doing work in speculative fiction that you have been inspired or intrigued by, that you recommend?

SMW: I’m very inspired by Octavia Butler; the incredible work of Nalo Hopkinson, who is a long-time friend and someone who has written beautiful speculative fiction for our current moment; Toni Cade Bambara. People who have written or created in alternative formats and means: Marsha P. Johnson, with her performance art and the way she would get up on stage and do all these weird, strange performances, is in my lineage of ancestors I would draw on. And then our living collaborators and mentors, people who I learn from every day, Dainty Smith, Ravyn Wngz, Aisha Sasha John, folks who are doing such incredible work. People who are telling stories centring disability, Leah Lakshmi Piepzna- Samarasinha, Eli Clare, adrienne maree brown, Leroy Moore. Audre Lorde, and how her work as a disabled woman, as a disabled writer, reminds us to relate across difference, has been really inspirational in my practice. I’m drawing a lineage of Black, queer, and trans heroes whom I’m looking up to, and also with whom I am working alongside in this current moment.

ROOM: We can also learn so much and take leadership from those who come after us. How do your experiences of parenthood influence your ideas of ancestors and futures?

SMW: Being a parent has been so incredible. When I first chose to become a parent—I had my daughter in 2011, and was pregnant in 2010 and 2011—there wasn’t a lot of visual representation of artist parents. It was like the thing you shouldn’t do if you want to have a career. I won’t say I was actively discouraged from becoming a parent, but the work conditions didn’t lend themselves to being a parent: nighttime gigs, weekend work, travel. But it actually has been a beautiful life being an artist parent. I’m so thankful. Having my daughter was the biggest creative project I ever did, the biggest creation I ever made. Getting to live with her and teach her about creative practice, to learn from her own creative practice, has really been incredible. I come from an artist family, so I was encouraged from a young age to be involved in the creative sphere, and to pass that on to my daughter is really encouraging and really helpful. We’re in this intergenerational artist family. It’s exciting. I will say that things seem to be getting better for artist parents. I’ve certainly seen a lot more visibility of artist parents in different kinds of art engagements, that maybe take place in the daytime and things like that.

ROOM: Within your work and in the world more broadly, multiply-marginalized disabled people are leading the fight against climate catastrophe but are routinely disposed of within mainstream environmental activism. What unique tools does disability justice bring to contemporary art about climate catastrophe and beyond?

SMW: Disability justice reminds us to be always looking at the future. Disability justice is rooted in sustainability, which is built into the tenet of disability justice, as articulated by Patty Berne in 2017. It’s rooted in this idea of interdependence, that we are necessarily reliant on each other, and that is actually a strength. It’s rooted in this idea that we take care of each other, and that means, literally, all living beings on this planet. So the potential to root fights against climate change in environmental justice organizing within BIPOC communities and Indigenous resurgence and Land Back and other justice movements like disability justice, this is where the magic is. I think about the MOVE organization in Philadelphia. I was really involved in the MOVE organization in Toronto in the 1990s. Here’s this group that was doing Black liberatory work, but was essentially, very radically so, an environmental justice group, often overlooked by white environmental activists at the time, led and founded by John Africa, somebody who was labeled with an intellectual disability. We have this confluence of disability, environmental justice, and Black liberatory organizing happening in MOVE, yet we don’t often think of MOVE as an environmental justice organization. So continuing to reimagine when we’re talking about climate change, centring our stories around Black and Indigenous authors, and asking, what do we need to be thinking through in terms of our relations to this land, in a way that is rooted in Indigenous resurgence, Land Back, Black justice, and Black liberatory struggle?

ROOM: In an episode of the Crip Times podcast in 2020, you talked about how amid protests against anti-Black racism during a pandemic, and while we search for solutions to questions around abolition and community care, artists find different and new ways to organize. What do you imagine the future of Black art, and art more generally, to be?

SMW: I really think that the youth movements we’re building now, these irresistible revolutions, are fueled by art. They’re led by artists, rooted in an artistic practice. Black Lives Matter is an art-based movement. Land Back is an art-based movement. These are artists who are making work about these conversations. So as we head forward into this future world that we’re building, art will continue to play a central organizing role. If we’re building abolitionist communities, we need to have artists involved in that design because they can dare to dream that another world is possible. They can help us paint a picture, write a story, describe what this world could look like. Once we’re living there, in the free, which we will get to in our lifetime, artists will get to be, as Assata Shakur always said, free to be so much more: free to be sculptors, gardeners, painters, while not having to struggle. We will all be free to do so much more once we’ve transformed society into a more just one where we won’t be living in constant struggle against white supremacy, transphobia, ableism, and classism. So Black art and Black creative organizing is going to be an essential part of this revolution. Revolution is not a one-time event, but rather a process, and we’re definitely in a revolutionary moment right now, which is working, because we’re working all together, across difference, as Audre Lorde said, and bringing an intersectionality to the organizing. So as we engage in this revolutionary struggle, artists are at the core. Once we get there, artists are going to literally paint our streets and fill our world with colour and vibrancy. And I’m really looking forward to getting there.

ROOM: We love the idea that as part of that future, art is valued in that way that it is not now. Finally, when we are experiencing constant and ongoing change, grief, and catastrophe, how do you keep adapting, and how do you stay hopeful?

SMW: I’ve been studying systems change and systems thinking for a couple of years now. I teach systems change and thinking. There’s this idea that all systems naturally go through a life cycle of growth and expansion, but also of collapse and reorganization, where new ideas are possible. Our current system is in a period of collapse and reorganization. We’re saying it’s time to get rid of things that are no longer serving us. Capitalism is heaving its last breath, and the pandemic has sped up collapse. This is the period where we get to plant the seeds for what is going to grow next: which forest is going to grow in the place of the one that has just burned down? So I’m very, very hopeful, because we get to both water the seeds that our ancestors planted for an abolitionist future, and plant our own seeds for the kinds of things we want to grow next, like community centres and libraries and artists’ spaces. So on the days where I feel overwhelmed by what we have to transform, I remind myself that change is assured, and we just need to be in this moment, in the fertile soil, which, let’s be real, sometimes feels like compost. But we need to be in the muck right now in order to get to where we’re going. I also get a lot of hope and inspiration from artists. There’s this incredible group called Fat Freddy’s Drop out of New Zealand, and they have a song called “Hope.” “Hope for a generation / Just beyond my reach / Not beyond my sight.” This idea of building toward something for your great-grandchildren: that is giving me a lot of hope.

ROOM: It’s been such a pleasure and so amazing to speak to you today. Thank you so much for your time.

SMW: Thank you so much for these great questions. It was a real joy.

May this piece guide us toward the support of the rights, safety, dignity, artistry, happiness, material and mutual aid, and scholarship of Black people worldwide, year-round.