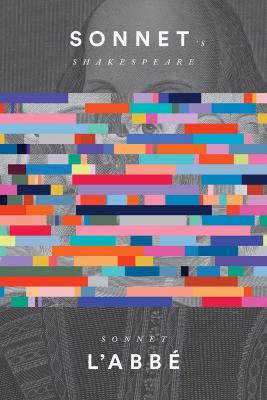

Sonnet L’Abbé’s third poetry collection is an incredibly ambitious project that assimilates William Shakespeare’s poetry, and it does not disappoint. Letter by letter, L’Abbé inserts her own language into his poetry, erasing and engulfing his words into her own. While the original sonnets are spoken over, Shakespeare’s voice is never entirely silenced. The Bard continues to haunt the work in the echo of each line.

L’Abbé uses this form to explore both her oppression and privilege. She grapples not only with being mixed race and coming from people who have been colonized, but also with being a settler living on Indigenous territories. Even from the first sonnet of the collection, she points to her own privilege in “the angloculture to which I am inseparably grafted.” She further examines settler colonialism and the idea of the “good, well-behaved immigrant” trope in XI: “Comfortable settlers choose not to know their own administration; I’m an ungrateful, hateful, ethnocentric immigrant if I defy the tolerance story.”

Troughout the collection, L’Abbé often writes bluntly and directly, forcing the reader to engage with their own relationship to settler colonialism and the myth of multiculturalism. This collection grapples with many intersecting issues, taking a critical look at feminism, environmentalism, and more.

While many of us who went through a colonial English school system may think of the sonnet as dense and impenetrable, Sonnet L’Abbé’s collection is approachable. Troughout these pages, L’Abbé brings in a number of modern markers that feel like old friends. In VIII, she asks “what music would sadly, sweetly sound your last zeptosecond.” She then provides a spectacular mixtape upon the page where “A Tribe Called Red will give sway to Bowie,” ending in the crescendo of “There’s love if you want it, don’t sound like no sonnet, sang Kuti, sang Bjork, sang e Verve.” Similarly, CIX explores Pokémon and transitions: “As easy as Meowth might ripen from money scrounger to jewel-foreheaded Persian, our transformation fromimmaturity to something more powerful.” At the end of the collection, you will find a list of entry points, with touchpoints like “only-minority-in-the-room,” “bouncing yuh backside,” and “raccoon nation.”

By displacing William Shakespeare’s work, Sonnet L’Abbé questions the literary canon in which he and other dead white men are heralded as the foundation for English literature. She confronts and dismantles the idea that some voices are more valuable than others, carving space for marginalized writers in a complex and multi- faceted way. Sonnet’s Shakespeare, an act of literary patricide, is a collection that is necessary to place in our literary canon today.