Part art criticism, part biography, part lyric journey, Painter, Poet, Mountain studies the intersection of inspiration, experience, and creation that is inherent to various forms of artistic expression.

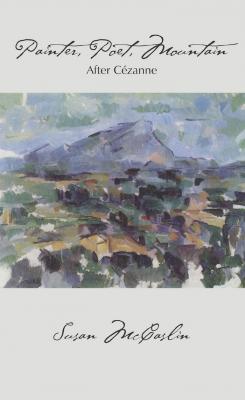

Ut pictura poesis (“Just as painting, so, too, poetry”), perhaps the most famous line of Horace’s Epistola ad Pisones (“Letter to the Piso Brothers”), is quoted toward the middle of Susan McCaslin’s fourteenth poetry collection, and could well have served as the book’s third epigraph (the collection opens on two quotations: one from Rilke’s Letters on Cézanne, the other from the painter himself). In this book, McCaslin explores Cézanne’s life and work, combining ekphrasis, character sketches, and lyric meditation. Beyond the post-impressionist himself, the poet is interested in considering his reception among other painters, philosophers, and writers, including the book’s speaker, an incarnation of McCaslin, whose peregrinations in France and British Columbia provide a structural backbone to the collection.

Not surprisingly, McCaslin considers some of Cézanne’s iconic paintings in a number of ekphrastic poems, which delight in their detailed, sometimes startling descriptions. So, for example, are “light-sculpted bathers / softened into a complex attention” in “Cézanne’s Sacre Coeur [sic] (Mont Sainte-Victoire),” while grasses are “chartreuse” in “Cézanne’s Baigneuses.” No less compelling are the poet’s portraits of Cézanne’s family and friends, like “La Mère,” which opens with a physical description:

Sombre in black

smudged gypsy cheekbones

white kerchief forming a slight widow’s peakWhy did he later douse her only portrait

in heavy black paint?

From there, the poem moves on to the rift between Cézanne and his family, illustrated by a biographical anecdote: “All we know / is that when Hortense burned his mother’s effects / he stumbled alone on the roadways / for hours”.

These portraits and references are accompanied by reflections on the painter’s place in art history. McCaslin also uses Cézanne’s life and paintings as a way to reflect on her writing. In “On Attending the Hungarian Sinfonetta’s Stabat Mater Concert (Église Saint Espirit [sic], Aix-en-Provence),” this reflection extends to a comparison with music, implicitly capable of something beyond the reach of poetry and the visual arts:

Sitting in the nave with Cézanne

who here regularly unaccountably attended mass

(convention? some deeper call?)I wonder who wouldn’t turn to music—

this tingling in the cells

Elsewhere, Cézanne’s France and the speaker’s home in British Columbia converge in the poems “Mont Sainte-Victoire and Golden Ears” and “Mont Sainte-Victoire and Mount Baker.” In the former, the speaker wonders how Cézanne would react to the Canadian landscape: “If Cézanne could be airlifted here / would he be undone?” Similarly, she looks to Cézanne’s artistic career as a mirror for her own in the second of these poems: “His mont and my mountain / precedent antecedent to / us late coming artists and poets”. These digressions stray somewhat from the sparkle of some of the earlier, more focused poems, but provide a nice sense of space in the volume. Part art criticism, part biography, part lyric journey, Painter, Poet, Mountain studies the intersection of inspiration, experience, and creation that is inherent to various forms of artistic expression.