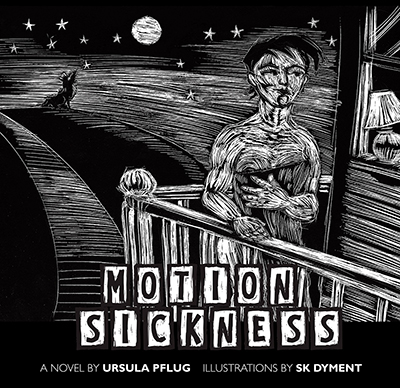

Speculative fiction author Ursula Pflug ventures into a new realm with Motion Sickness, a “flash novel” told in fifty-five chapters of exactly five hundred words, accompanied by scratchboard illustrations by SK Dyment.

Twenty-year-old Penelope spends most of her time getting “blotto” and playing music. After she meets and jams with an older bass player named Theo and they mistakenly swap journals, she decides he’s “Mr. Right” based on a line of his poetry: “Hearts on ropes and flowers on telephone poles.” Unfortunately, when she returns to the club to look for him, she ends up in a drugged threesome with the “potentially” dangerous Stan and his girlfriend. The encounter leaves Penelope pregnant, and Stan obsessed with her. To make matters worse, it’s later revealed that Theo is married.

Motion Sickness is disorienting—dizzying, even. Penelope is an unreliable narrator: she’s easily distracted, preoccupied, and, frequently, drunk. In one scene, she thinks to herself: “If you drank less you might remember more.” She’s “so good at living in the present [she] didn’t even remember last week’s conversations.” Facts introduced in one chapter are forgotten in later ones, and speculations grow into belief.

Because I spent time looking at Dyment’s illustrations before reading each section, the “flash novel” format broke the flow of reading for me—even when the new chapter began seconds after the previous one ended. Initially, I flipped back to reread scenes, but when I stopped and accepted the reality of each chapter as a self-contained flash fiction, I became more fully immersed in Penelope’s in-the-moment realities. The format of the novel perfectly reflects and enhances the perspective of the narrator—the disjointed, disconnected vignettes recreate the feeling of being twenty, self-focused, overly imaginative, and drunk.

At times, the supporting characters feel underdeveloped—which can largely be attributed to Penelope’s narrow point of view—and, in particular, I was frustrated by the storyline with Theo’s wife, Annabelle. The only thing we ever learn about Annabelle is that she works at the hospital and broke her husband’s leg with a baseball bat because of his emotional affair with Penelope. It’s an easy cop-out, allowing the reader to side with Penelope in her desire to break up their relationship without any real emotional barriers or a nuanced understanding of what it means to fall in love.

Pflug’s history as a speculative fiction writer is apparent—Penelope’s story exists out of time and without the boundaries of logic. Toronto is reduced to a self-contained microcosm, where people are known only on a first-name basis and stumble into each other in unexpected places. In other ways, the story is firmly rooted in reality. There is no magic here, only gritty surrealism, an inverted reality that is complemented by Dyment’s illustrations. As a side note, colour (especially red) plays a huge role in the story, and I thought it was an interesting choice to use black and white art, and leave colour and its significance to the reader’s imagination.