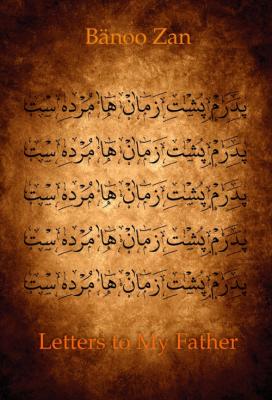

Bänoo Zan’s second book of poetry, Letters to My Father, opens with her rationale for seeking refuge in poetry, and fleeing from stories.

Bänoo Zan’s second book of poetry, Letters to My Father, opens with her rationale for seeking refuge in poetry, and fleeing from stories. “Stories distort the truth by virtue of their claim to facts. It is only when stories have exhausted themselves that poetry happens,” she writes. The poems, which are dedicated to and about her father, explore Zan’s search for reconciliation after learning about his death in 2012. Zan didn’t attend her father’s funeral or several memorial services in Iran, but he soon became the muse for this deeply personal collection.

While Zan and her father may have been separated by borders and continents, her poetry resists being broken up by descriptive titles or section dividers. The poems, which are simply numbered one through forty-one, flow seamlessly from one to the next without the narrative constraints of a story, all while achieving continuity and masterfully weaving together imagery from both locales. From tragedies and epics to ghazal and qasidas—which are Arabic words for poetic forms—Zan skillfully alludes to the Greek philosopher, Socrates, in the same breath as Mansūr al-Hallāj, a Persian mystic and poet. Time and geography are intertwined, where Zan refers to her father as the country she left, a “land of conflicts / unexplored,” in which she is still very much a citizen.

Despite being a poet with a facility for language, the overwhelming silence that Zan describes between daughter and father sits at the heart of their struggle for familial communication. “Your loss / is the absence of words / and there is no love / where there are no words,” she laments. These conflicted feelings can be traced through every single poem, where silence in life and death is a barrier to reconciliation. “Silence was our language,” Zan writes, where his “lips guarded [his] heart”, and his voice was a “silent kiss.” His death was but a “rehearsal for life,” where a daughter finds herself caught in a war that “doesn’t end / with the end of life” and must now learn to live after loss. While he is free from “life, love / pain and faith,” she must walk the earth bearing the weight of grief.

The most emotional use of language comes in one of the final poems, where Zan slips from using “Baba,” the Persian term for father, to a single utterance of “Dad.” Toward the end of the collection, the poet mourns the silence that defined this daughter-father relationship: “Love made us cowards / with more pauses than words.” Zan mentions that she decided not to use her introductory remarks as a confessional, and it’s easy to see why—her poems reveal far more. If stories distort the truth because of their claim to facts, as Zan says, and poetry allows us to write our own stories, then the poet’s truths lie somewhere within these lines—look for them.