Politics, religion, and science fiction are an ambitious mix in Gila Green’s first novel; her version of the near future affirms that religion-based misogyny is alive and thriving, as is technology: robot child-minders and glitchy mind-reading cell phones serve as background to a satirical allegory on wealth and the cult of celebrity.

The novel begins in 2019: Eve and Manny, a young, secular Jewish couple, are engaged and living together in Israel, a country recovering from a civil war. Unbeknownst to Eve, Manny has had a religious epiphany and adopts a strict Orthodox lifestyle seemingly overnight, becoming a different person. Unfortunately, the reader doesn’t get a chance to see the Manny that Eve fell in love with; the Manny she marries is condescending, manipulative, and highly contemptuous of her inability to accept his sudden religiosity. Yet because of a vision where a holographic, eerily blue-eyed boy appears and implores Eve to marry Manny or he, the boy, will never have a chance to be born, Eve compromises her own beliefs and marries into the Orthodoxy.

The second half of the novel takes place in 2032: we learn that Eve’s visions have continued, yet Manny dismisses these as nonsensical and evil, while his rituals are traditional and holy. His clueless hypocrisy is painful, and Eve’s obeisance is disappointing. Aside from the maddening characters, Green’s phrasing choices can be superfluous, often detracting from the simplicity of quiet moments: i.e., characters do not eat soup, they inhale it. Or on page 127, “Eve sits on the bottom carpeted stair with her arms wrapped around her knees and listens to her husband brush his teeth until she can’t keep her eyes open.” The reader wonders how many hours Manny devotes to oral hygiene.

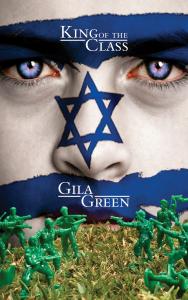

Green also introduces a Messiah allegory into this politically thoughtful work: Eve as Mary, Manny as Joseph, and Netsach as Jesus. Netsach (a Hebrew word meaning eminence and perpetuity) is a popular eleven-year old boy, the “King of the Class”: definitely analogous to Jesus as “King of the Jews,” replete with a symbolic resurrection.

There is a complicated intelligence in this novel, only mildly sullied by awkward phrasing and some suspiciously convenient plot devices, but Green—and the reader—has fun with the sci-fi and satirical elements. King of the Class deserves a deeper analysis than what the space allotted here allows for, but the questions it raises about motherhood, religion, and politics will stay with the reader long after the cover is closed.