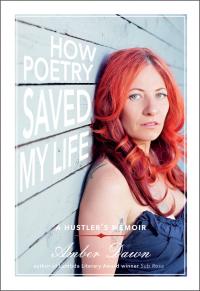

Amber Dawn’s second book, sections of which were first published in Room (30:2; 35:4), is a mixed-genre work chronicling the author’s experience in the sex industry and her experience of poetry as a life-changing force. The book attempts to de-stigmatize sex-work, which is still often seen as something “others” do. Dawn’s account, which includes wise reflections on class, queer identity, and the way in which sex-work can change its practitioners, is compulsively readable and nuanced, the readability being a result not only of the subject matter, but also of Dawn’s narrative style, which is conversational and often includes direct address to the reader. Dawn’s book attempts also to de-stigmatize poetry, a genre which is often viewed as being esoteric, inaccessible, or intellectually elite. While Dawn’s prose sections are often excellent, it is her poetry that is of primary interest to me. In the preface, Dawn notes that “only a form as dynamic and fundamentally creative as poetry could provide a medium” for her story. The book is a sustained argument for poetry’s enduring validity and immediacy. Dawn describes reading Kate Braid’s poetry in an SRO-hotel with a fellow sex-trade worker, an event which she says “urged her onward” (14).

Dawn bravely includes some of her early poetic efforts from this period: “Chevron Restroom 1212 East Hastings”; “Sex Workers Feet”—poems that make up in immediacy what they lack in conventional merit. It is also fascinating to see Dawn’s poetic voice develop from these efforts to the splendid later poems including “You are Here (a Map),” “Sensual Bliss Massage & More,” and the prose poem “What’s My Mother’s F***ing Name”—a startling meditation on bodies, agency, and objectification.

Playing with traditional forms, Dawn’s poems are accessible, often utilizing a conversational tone and direct address. They are also very lyrical, comprised of imagery that is by turns beautiful, “All the hanging pictures are of water-coloured flowers. Roses / lilies, daffodils, a quiet fire / in a cool green meadow whispering” (“You Are Here [A Map]”), intriguing “Tonight your hands are named exile and limbo” (“You Are Here [A Map]”), and visceral “how blood / enters the open pores of the chopping board is not important” (“Missing Children”). Interspersing poetry with personal essay is an ingenious way to get non-poetry readers interested in poetry. Dawn’s apology for the form is thus convincing and the mixed-genre form becomes a medium through which her important story, and maybe poetry itself, will reach a wider audience.