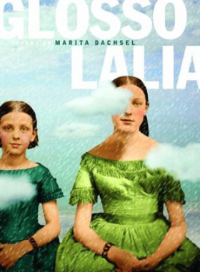

Roomie Jennifer Zilm reviews Marita Dachsel’s Glossolalia.

There are many versions of the story,”says Eliza Roxcy Snow at the end of B.C. poet Marita Dachsel’s second trade collection (several poems of which appeared in Room 32:3). Snow is one of thirty-four wives of the 19th century prophet Joseph Smith who speaks through Dachsel in verse primarily characterized by short, lyrical and direct lines, yet punctuated by prose pieces, an erasure, and other innovative uses of page space. With such a myriad of voices it is inevitable that sometimes the voices do blur together and one senses this might be intentional, a part of the cacophony of tongues hinted at by the title. For the most part, however, Dachsel is to be commend-ed for conveying the distinctiveness of these voices though the aforementioned experiments with space and form and by a strong narrative imagination, which imbues plausibity to these women. Particularly striking are the voices of “Fanny Alger,” the Smiths’s maid who longs for the affection of Joseph Smith’s one legal wife Emma. Also striking is the voice of the middle-aged midwife “Patty Bartlett Sessions,” who regrets the role she has played “delivering” women into the polygamous lifestyle. There is a humour in both these poems that balances the individual women’s pathos that is often found throughout the book.

The two “loudest” voices in the collection are that of Emma and of Eliza. These women took different paths within the early Mormon Church. After Smith’s assassination, Emma chose not to follow Smith’s successor Brigham Young to Utah and vociferously denied Smith’s polygamous activity. Snow, who was a poet, chose to move with the early Mormons and married Young (for time, not eternity—a distinction Dachsel explains in her notes). Both women are marked by their childbearing, or, in Eliza’s case, lack thereof. In a striking pas-sage early in the book Emma notes in an address to her husband: “You used to say I looked beautiful / pregnant … But my babies were buried / at a rate I considered laboring / squatted over a muddy hole.”

Emma’s four poems are scattered at intervals throughout the book, and she is often a subject in poems of other wives. Eliza, whose voice closes the book, opens her testimony by noting that she “will never feel the ache / of filling breasts / heavy for release.” Eliza is the most nuanced of Dachsel’s voices. She is vocal in her sexual desire, refusing to be just a wife. Looking back on her life, she laments the squandered potential of the female saints, and recounts using her sexuality to advance feminist theological positions: “I told him / a father in heaven is a fine idea, / but don’t we need a mother too? Every man deserves at least one wife, / even God. / With his hand/ on my thigh / he agreed.” In the sequence, however, just as in the many of the poems, the possibilities for women’s advancement in the early move-ment are squashed as the women are inevitably played against each other. Emma’s menacing presence lingers throughout Eliza’s account, hinting at the former woman’s violence against the latter. The sexual and spiritual kin-ship between Joseph and Eliza is ultimately eclipsed by this rivalry, and it is the strife among sister-wives that closes the book.