On December 6, 1989, a gunman raging against feminists killed fourteen women at Montreal’s École Polytechnique. In 1991, that day was declared the National Day of Remembrance and Action on Violence Against Women. It is sobering to contemplate how little has changed.

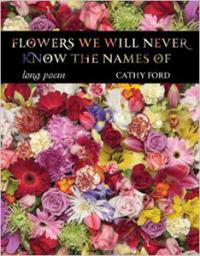

Flowers We Will Never Know the Names Of is Cathy Ford’s commemoration of the victims through a long poem using the language of flowers. The poem is constructed of two main parts: the first a numbered sequence that alphabetically incorporates the names of the murdered women and the second an alphabetical exploration of flowers and their symbology. The link between the two parts is seamless and beautifully moves the reader from the particularity of loss to an overwhelming sense of grief.

The first fourteen pages identify the victims’ first names but not the names of specific flowers. The flower imagery is general:

In flowers, a language where one word, a naming, is breath,

is voice, is soul

In the second part, Ford revels in precise flowers. The poem moves smoothly using boldface to highlight letters in the alphabet sequence and italics for the dozens of names of flowers:

night falls: blue convolvulus, night convolvulus, bleeds white

not to forget: rosemary, modesty, night jasmine, kind hearted in

sorrow

The structure is elaborate and careful, but Ford mindfully breaks the patterns when doing so suits the poem, just as so much was broken with the deaths of these women. In a particularly powerful pattern change, she omits end punctuation for most of the poem, but the final page is heavy with periods:

Roses. Remembrance. By any other unknown

name. Do not. Forgetting. Burn this poem.

The exhortation to burn the poem is preceded by the command “Do not forget,” and clearly poetry is a way to remember. Naming is also a way of identifying or giving life, so Ford’s control of when names are used and the abundance of flower names emphasize how the fourteen women’s lives have been shortened. They are flowers lost.

The poem is finely calibrated and extremely dense, often oblique. At times, emotion overtakes syntax, as surely as that happens in life and in the face of death. Feelings are keenly developed by the detailed imagery. Ford supplies an afterword and a section called “Notes on the Text,” which seem rather academic compared to the immense pathos of the poetry.

Cathy Ford approaches this terrible subject with skill and passion. And in the spirit of the poem, I think there’s only one way to end this review: Geneviève Bergeron, Hélène Colgan, Nathalie Croteau, Barbara Daigneault, Anne-Marie Edward, Maud Haviernick, Barbara Klucznik-Widajewicz, Maryse Laganière, Maryse Leclair, Anne-Marie Lemay, Sonia Pelletier, Michèle Richard, Annie St-Arneault, and Annie Turcotte.