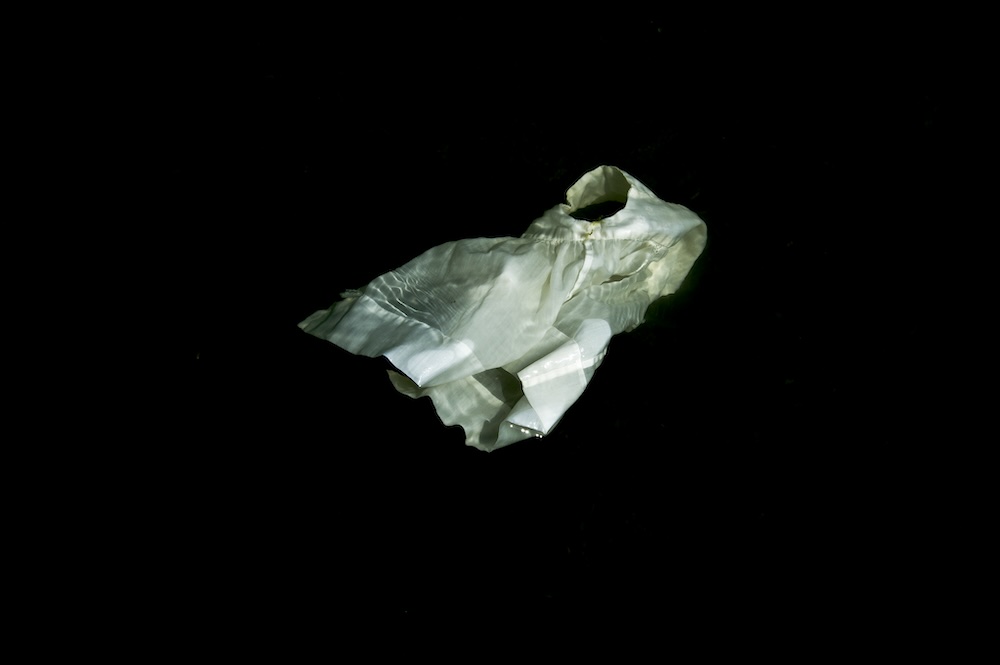

To celebrate the publication of issue 46.3 Ghosts, Room would like to share a story from one of our issue contributors, Devon Borkowski. You can read “Ten Rules For Living In A Haunted House” in print and many other haunting stories and poems by ordering the issue online.

One.

Accept that every house is haunted. Your dead are just a bit livelier than most.

Two.

If the three Lenape children standing in your backyard make you feel guilty, you probably deserve to. They were there before you—both in the most obvious sense and in the fact that you saw them during the house tour—three little slivers of shimmering air hovering around what is now the above-ground pool. The realtor sat you down gently and explained that all the houses in the area had this sort of “long-term activity” from the tribe that used to live on the land but that they rarely ever fully manifested. These ones have, though. So now you have three little children, translucent and hovering around the edge of your property. You tried, at first, to do the right thing. You called the nearest museum with an American Indian exhibit, but they said they only take physical artifacts and that the haunting’s gone on so long that finding the children’s bones probably still wouldn’t do any good. So you don’t use the pool much, and you don’t go outside until after your morning coffee.

Three.

When turning what was a bedroom into a home office, negotiating a few furniture compromises with the teenager who haunts it goes a long way. She’s chatty—at least, as far as any of them can be. She doesn’t speak, per se, but you feel her voice like a headband that’s too tight, an ache behind your ears. The louder she gets, the more the headband tightens, and the more it starts to feel like a sharp spike in barometric pressure. Your nose starts to run, then bleed, and you’re crying and screaming, and you swear your brain’s about to leak from your ears. The point is the two of you learn to communicate. You buy a trundle bed to leave pulled out whenever you’re not in the room and hang a joy division poster on the back of the door.

Four.

The Smiling Man is not allowed inside. He puts his face too close to the windows, sometimes even taps on the glass if you’ve gone too long without looking his way. You line all the doorways with ground black tourmaline and get some chic signs off Etsy, warning your living houseguests to watch their feet. Even the other ghosts breathe easier when you’re done, which makes you worry for the three children in the yard. You plant rosemary and lavender around what seem to be their favourite spots, and you hope that’s good enough.

Five.

Disembodied wailing emanating from the attic is a pretty major cock block, especially if the main bedroom seems directly below the source. There are steps that can be taken to mitigate this. The first is wine. A pleasant wine buzz makes everything feel softer and less immediate and does great things for your sex drive. Unfortunately, it does nothing for the morning after, and the few times you bring a man over, you run the risk of whiskey-dick. The second solution is soundproofing. You get halfway through duct-taping insulation foam to your ceiling before you realize that even if this does work, this looks like the kind of crazy that means no one will ever sleep with you again. So for attempt number three, you go straight to the source. You tear through the attic, wailing echoing off the walls, making your skin cold, your hair stand on end. It stops when you find a loose side of a long-dismantled cradle. The nails are rusted, sticking from the posts like teeth. When you hold it, you feel bereft, a magnitude of loss you’ve never known, and only when you put it down do you realize you’ve been crying. The next day, you go to Walmart and bring home a bassinet and a doll that you swaddle in a beach towel you no longer use. It’s a bitch to bring up the attic ladder, but once you’ve got everything in place, a woman appears. Her face bends over the doll, you can’t see it through her hair, but slowly the bassinet begins to rock, and you never hear anything from the attic again.

Six.

The Lenape children have started coming into the house now, which they hadn’t done before. They don’t look impressed with your interior decorating, but they didn’t ever look impressed outside either. “Tough crowd,” you say, and they don’t say anything back. Mostly they just huddle very close together, their little translucent arms and legs overlapping and passing through one another until they’re almost one, many-limbed being, staring at you with six unblinking eyes. You feel like they’ve probably earned the right to do this, but you wish they wouldn’t insist on standing in the middle of your kitchen. It makes it very hard to eat.

Seven.

Your mother got you a little cross wall hanging as a housewarming gift. You hang it in the living room because you know she’ll say something if she can’t see it up and also because you figure at this point it can’t hurt. Every other Thursday, you find it inverted. This is annoying because it’s starting to scuff the walls, but you decide there are probably worse problems.

Eight.

Phone calls don’t really go through to your house. You assume it’s a problem with your router at first, but of course, it is not. You find that you can get reception outside, so long as you stand near the lavender plot and wear a silver ring on the hand you hold the phone with. Texting seems to work fine, though, and you’ve never liked making phone calls anyway.

Nine.

One morning you wake up to screams. You run downstairs without even brushing your teeth first because there are some things you get used to in a haunted house, but screaming isn’t one of them. One of the Lenape kids—the middle one, who can’t be any older than ten—is staring out the window and howling like her heart’s been set on fire. It takes you a moment to realize that the heat coming off her is rage. You have to climb up around the sink to get the same view—you’re afraid to share a window, you’re worried about your organs cooking if you get too close to her. Outside is a man on horseback. He’s so faint, you see the tree through him better than you can see his face, but you can see the rifle in his white hands. You draw your own conclusions. The two oldest children vanish, and reappear right in front of the rider, enmeshed over each other as they often are in your home. The third child stays behind, hovering by your dishwasher. His eyes are huge and impossibly dark, and he will not stop staring at you—you, a grown adult squatting around the kitchen sink while two small children scream and scream in your yard. The side of your above-ground pool is starting to buckle, and there’s a charred circle of grass where the children stand. You grab a Mortontin from the Lazy Susan and run outside. You’re not really sure what you expect, tossing a handful of kosher salt into the mounted man’s chest—the only place you’re tall enough to reach. What does happen is a peppering of holes straight through the washed out silver buttons of his coat, the salt seems to eat out from the spots where it strikes. You watch as the holes’ edges seem to burn, ropey ectoplasm stretching and snapping like rolls of old film. The children don’t thank you when the man is gone. They seem to spend more time outside after that, though, taking turns watching the horizon.

Ten.

You get a little more proactive about your situation. You hang a second cross upside down in the dining room. Three weeks go by before you feel confident the one in the living room will now be left alone. The woman in the attic—well, she seems content. You do hang a sign, though, telling any future homeowners the bassinet is not to be touched. You get your phone a silver case. It’s a pricey but efficient solution. For the Smiling Man, you call your mother, who calls a priest, who brings in an exorcist. You didn’t know that was a job a person could have until one stands at your door. The girl in your home office seems a lot happier after that, moving around the other rooms of the house with a new ease. She needs very little from you, so you let her be. The children are more complicated. You try the museum again, just to get the same answer as last time. Contacting the State’s Office generates even less interest. Finally, you just Google “how to contact Lenape people” and find the Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape tribal council’s email address. It takes a few days to hear back. And then a few more days for them to send a representative. She is polite and a little sad to be here, though she assures you she takes calls about situations like this often. “This whole continent is haunted,” she says, kind but firm, before she heads to the backyard. You watch through the window for a moment. You’ve grown kind of fond of the children. You feel almost protective of them, though you know you have no right to be. You watch as she kneels down in front of the oldest, the other two crowded in close. You watch as she talks gently to them and takes him by his little hand.