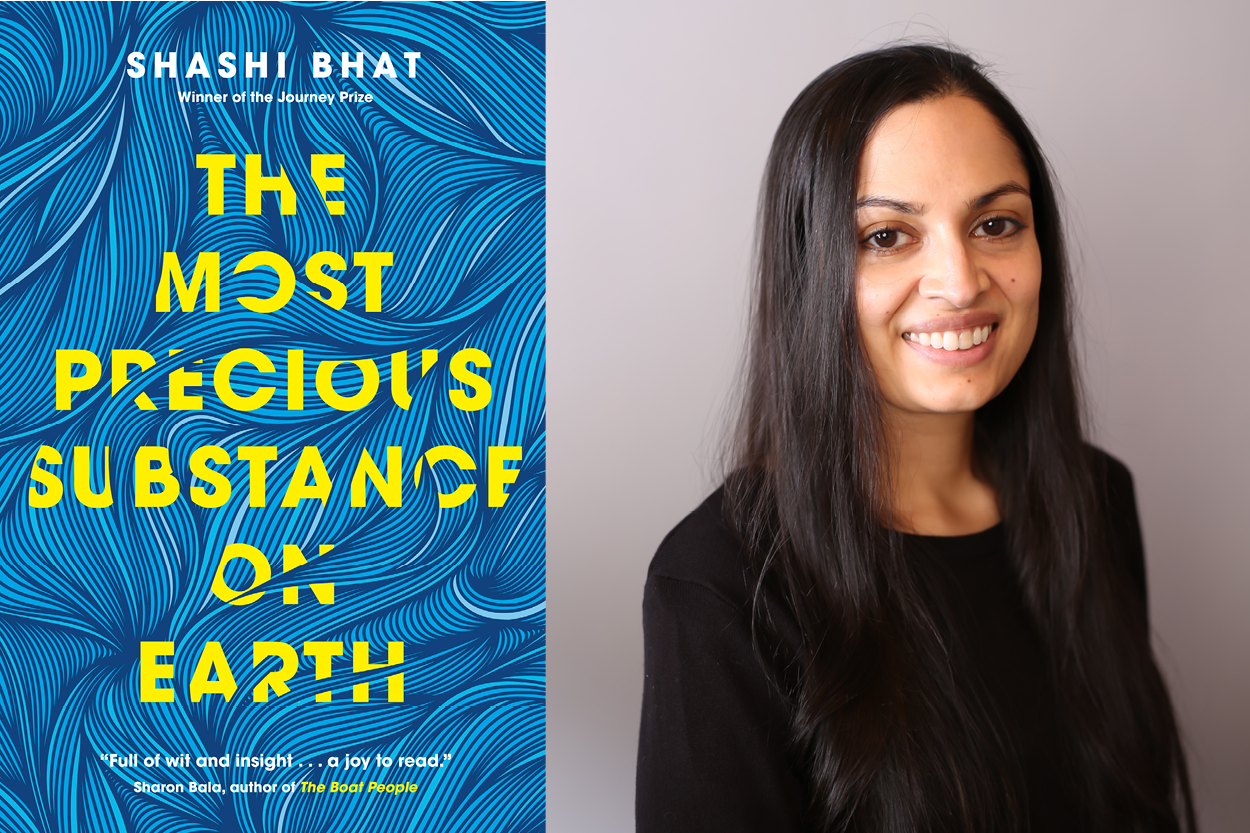

The judge for Room’s 2022 Fiction Contest is Shashi Bhat!

Shashi Bhat is the author of The Most Precious Substance on Earth (McClelland & Stewart, Canada, Fall 2021; Grand Central Publishing, US, Spring 2022) and a short story collection forthcoming from McClelland & Stewart. Her debut novel, The Family Took Shape (Cormorant, 2013), was a finalist for the Thomas Raddall Atlantic Fiction Award. She was a winner of the Journey Prize and has been shortlisted for a National Magazine Award and the RBC Bronwen Wallace Award for Emerging Writers. Shashi’s fiction has appeared in publications including Best Canadian Stories 2018, 2019, & 2021, Journey Prize Stories 24 & 30, The New Quarterly, The Malahat Review, The Fiddlehead,and others. Shashi is editor of EVENT and teaches creative writing at Douglas College.

Read our conversation below to learn about Shashi’s creative process, the ways she challenges what it means to be a “strong woman”, the advice she would give to new and emerging writers, and what ‘90s trend she wishes we could bring back.

This year’s Fiction Contest is open until March 5th, 2022. Find out more information about the contest, the prizes, and how to enter here.

[This interview was conducted via email.]

———-

ROOM: Your novel The Most Precious Substance on Earth pushes boundaries, and defies genre and classification. It’s not quite a novel, not quite a short story collection – it’s both. Told in a series of vignettes or snapshots – that while able to be read by themselves, rely on the context in the other stories to come together, and show the full picture. Why did you choose to put the book together in this way?

Shashi Bhat: The book is a novel-in-stories that follows one narrator from age 14 to her mid-30s. The short story is my favourite form. I love its economy and the way it compresses and showcases the narrative arc. I also love the short story’s potential for a gut-punch ending without the catharsis of resolution, and this seemed to make sense for a book about a character with unresolved trauma. On the other hand, I like the novel’s expanded opportunity to explore a character over time. I wanted the ending of each story/chapter to feel like a lump in the throat, and for the book to have a sense of building discomfort, because I think that’s the way the narrator feels—consistently uncomfortable. Structuring the book as a series of short stories with time gaps in between also allowed for this effect of omission, which made sense to me in a narrative about a woman’s silence.

ROOM: Incredible! Can you tell us a bit about your creative process? Do you find structure and routine helpful, or do you tend to go with the flow?

SB: My process is dependent on my schedule. I teach creative writing at Douglas College and am also editor of EVENT magazine, so during the school year my bandwidth for writing tends to be limited. I write as much as I can in the summers. What I also find useful is meeting with other writers in cafes (or now on Zoom)—it really motivates me to be around that energy of other writers, and to have people to chat with during the breaks!

ROOM: What excites you as a writer? What excites you as a reader?

SB: The things that excite me in both reading and writing are tonal range, lyricism, and potent emotion.

ROOM: Strength and bravery are so often depicted as boldness, or loudness. As big flashy statements, or epic battles, or dramatic gestures. However, your book explores the strength and courage in silence – in keeping things to yourself, in holding secrets. Why was it important for you to depict strength in this way? Why was silence, or the idea of keeping silent such integral parts of this story?

SB: At some point I became frustrated hearing about “strong female characters,” at least when the term is used in the simplistic sense. It made me angry to think that for a lot of women, to be “strong” would require ignoring reality. I resented the implication that to be or do the opposite was to be weak. It was only gradually, after having written several stories, that I realized the book was about silence.

The more statistics I read the more powerful the idea seemed. I kept reading about how most sexual assaults go unreported and about how victims of sexual abuse often don’t speak about it until decades later—if ever. I think it takes extraordinary strength to keep a secret like that. I wanted to write a book that reflected that experience and was honest about it.

ROOM: A large part of The Most Precious Substance on Earth is set in the 90s, and it’s full of pop culture references and nostalgia. As a child of the 90s, I need to know – if you had to bring back two iconic pieces of 90s culture (TV, movies, art, music, fashion, slang) to the present day – what would you bring back? Additionally, what do you think should stay in the 90s, and never come back?

SB: I always liked cargo pants. Are they back in style yet? I don’t know. I would also bring back teen dramas with quieter plots. And maybe the word “chillax.”

For the things that I wish would stay in the ‘90s: dial-up internet. And pogs, but I don’t think anyone was planning to resurrect those.

ROOM: You are going to be judging ROOM’S Fiction contest for 2022, and you’ve judged multiple writing contests before. In your opinion, what sets apart a great work of fiction?

SB: I’m drawn to stories with emotional impact, whatever emotions those are. I look for tension and momentum and surprise and authority, and I admire stories where the aesthetics are as compelling as the content.

ROOM: Not only are you a published writer, and an editor, but you’re also a teacher of creative writing… What advice do you have for emerging, new, or unpublished writers?

SB: The advice I have is what I wish someone had told me: Make writing a priority. Make writer friends who are supportive rather than competitive. And write towards where the energy is, what you’re excited about, not what you think you’re supposed to write.

———-