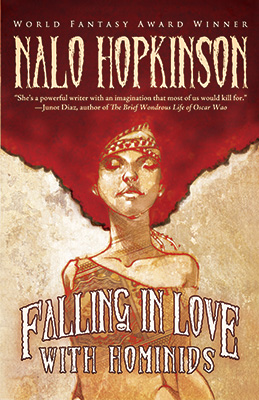

Falling in Love with Hominids is a collection of fantastical short stories filled with an innovatory mix of characters grappling with existential and everyday questions—what’s for breakfast? should I bring a child into the world? how did that elephant land in my living room?

Falling in Love with Hominids is a collection of fantastical short stories filled with an innovatory mix of characters grappling with existential and everyday questions—what’s for breakfast? should I bring a child into the world? how did that elephant land in my living room? Written over the course of a decade, many of the stories play well together, sharing a succulent, earthy-otherworldliness that Nalo Hopkinson’s fans know and adore.

Character is king here. Hopkinson always imbues her narratives with awareness of race, class, gender, and privilege that never gets in the way of the story—yet it’s remarkable because it underscores the lack of this awareness in most media. A fierce opening story, “The Easthound” has post-apocalyptic teenagers so fleshed out and intriguing that they blow away the paper-thin “heroes” dominating most YA books and cinema.

Though it’s not a YA book, there are quite a few young characters given the compassionate Hopkinson treatment: notably in a hamadryad-myth based tale, where a “fat” teen fuses with a tree spirit to triumph at a cruel party game. In the book’s introduction, Hopkinson describes her development from despondent teen to a fifty-something optimist who learned to “trust humans in general will strive to make things better for themselves and their communities . . . despite the fact that sometimes I just need to shake my fist at a mofo.”

There are occasions in this book where there isn’t enough room to establish an alternate world and tell a story there, particularly in the micro-fiction pieces. This and a few devices that feel forced, such as the story entirely narrated to a rat-orchid hybrid, are the only things not to fall in love with in this otherwise adoration-worthy collection.

Hopkinson’s reframing of The Tempest uses a dual narrative and themes of internallized racism told by now-siblings Ariel and Caliban: “The real storm? Is our mother Sycorax; his and mine. If you ever see her hair flying around her head when she dash at you in anger.” And the story “Old Habits,” situated in a ghost mall, where in the first paragraph the narrator tells us, “This is not going to be one of those stories where the surprise twist is and he was dead!”

All in all, Falling in Love with Hominids is an entertaining and humane book that affirms why Junot Díaz refers to Hopkinson as “one of our most important writers.”