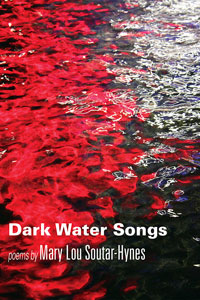

The poems in Dark Water Songs by Mary Lou Soutar-Hynes touch on the political, the natural, the concrete, and the abstract. From the streets of Toronto to tropical islands, “From Perth to Edinburgh by Rail” (21) Soutar-Hynes takes us through urban and rural landscapes following the “crimson certainty” (61) of her heart’s inclinations.

The poems in Dark Water Songs touch on the political, the natural, the concrete, and the abstract. From the streets of Toronto to tropical islands, “From Perth to Edinburgh by Rail” (21) Soutar-Hynes takes us through urban and rural landscapes following the “crimson certainty” (61) of her heart’s inclinations.

The collection is divided into four sections: “In the Manner of Tides,” “Close to Home,” “Slippery,” and “Other Gravities.” Not surprisingly, water—the sea, the tides, the river, the lake—figures prominently in the work, as does the stuff of water—islands, salt, sand, and lighthouses. This theme runs so strongly through the first two sections that even a poem like “Implicated” (16), which makes no mention of water and is political in tone, brought to mind an aging leader of a small island nation.

This theme loses strength by the sections “Slippery” and “Other Gravities.” Sailboats and anchors still pop up, but as a reader, I was becoming more aware of and more interested in the glimpses of the poet’s life seen almost as “clusters of intimacy” (75) in the poems.

Narratives are partially told but mostly obscured. “Discernment” (73) is one example, where Soutar-Hynes uses landing a plane in fog as a metaphor for perspective. Near the end of the piece, a third person appears in parenthesis: “Beautiful, she said of your heart’s / steady beat: I saved you / a picture.” This dialogue changes the “pockets of turbulence preferable to disaster” earlier in the poem to a comment on this relationship. But that’s all we really get of it.

“The Weight of Storms” (40) beautifully depicts the frozen existence of deep winter in Ontario: “No birds at the feeder / no squirrels foraging / through lilacs frozen antlers.” The poet uses this environment as a metaphor for the tone set by argument between intimates. “We play our separate / hands from separate rooms—/ lost solitudes—awaiting ploughs / to pry us free.” These snippets appear throughout the book, scattered between abstract meditations like “Perhaps” (52) and observations of the natural and constructed world.

Soutar-Hynes’s use of space, line-breaks, and stanza breaks lends many poems in the collection not only the poet’s voice—I can hear her pauses, hear how she would likely read aloud—but a concrete quality. I truly hope that the island-like shapes formed by poems like “Along Rosedale Valley Road” (56) depict archipelagos found in some old atlas.

As I read Dark Water Songs, I was increasingly aware of the poet’s consciousness, or the “brisk salt of / [her] waking thought” (31) and the effect left me curious about her, her work, and her life.