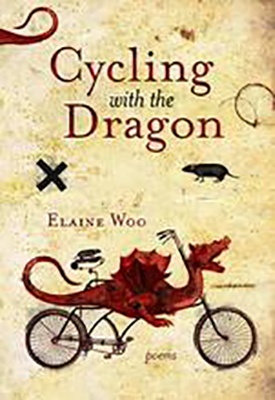

Elaine Woo’s debut poetry collection opens with a birth, a book slipping into life surrounded by a “throng of reading witnesses.” Cycling with the Dragon is this book, a collection interested in the intersection of life and craft, the forming and gathering of thought and word. Woo’s speaker takes on traditional womanhood and the world as it stands, and emerges transmuted, a strong and able bellwether to an alternative way of being.

The world of Cycling is not a comfortable one. In the work’s early pages, Woo’s speaker is plagued by childhood ills both usual—the accidental breaking of a cherished vase, the sudden results of stomach upset—and specific—conflict with a forceful mother, experienced racism, isolating shyness. The speaker chooses books as her “adopted family,” the pages offering relief: “These authors demure: never wielded / a wooden feather duster handle / across my eczema-prone skin, unlike mother.” Starved for understanding, the speaker watches spiders spin webs across her ceiling, “hoping to capture sustenance,” and wonders if she too should grow eight legs, become something else.

Outside voices creep into the collection’s later sections, as Woo begins to unravel writing as a woman in the face of societal expectations. In “The Hood,” a neighbour claims “writing is just your hobby / not your real work,” while a husband insinuates: “Your work is stress-free and serene. / Childcare? House care? / Easy, peasy . . . no dog eat dog.” A mother-in-law surfaces, criticizing: “tells my son I’m a bad mother.” Babies demand attention, dishes pile in the sink.

Woo answers these allegations by taking space. In “A Nod to Myself,” the speaker retreats upstairs to “draw a blanket of silence / and darkness over my torso / horizontal for minutes I feel myself ebbing back.” She delves deeper into writing as rest: “I unearth solace erudition in my page-traversing pencil.”

And as her speaker makes room for herself, Woo writes a different way forward, that of creation as transgression and transformation. She returns, in “Feminine Ecology,” to the conflation of birth with writing, the stringing of words a deeply muscular act, the speaker in her aging body “birthing the linguistic.” Woo’s woman is progenitor on her own terms.

The collection is littered with bright description. Woo’s subjects are deceptively simple—a heron at Lonsdale Quay, a seal on the mudflats, the “bundle of toothpick masts” of a childhood marina. In poems like “Season Off-Key,” the lines break and drift across the page, the echo and pause between words creating stream-of-consciousness immediacy, a sense of discovering and confession. Woo rarely puts a foot wrong, her images finding brilliance in the familiar: “a tug lit as though by bioluminescence / laboriously pulls a rusty barge; / a mouse hauling a dinosaur across moiré.”

Woo’s chosen family serves her well. Cycling with the Dragon is a powerful debut: something crying out and altogether new.