Having already claimed over one million lives globally, the COVID-19 pandemic is a time of great masking. As a response to the highly contagious virus, health authorities have demanded that we all wear masks. This essay is a reflection on masking as inspired by the pandemic, and the pressures it has put on our social norms and cultural mythologies. A microscopic virus, neither alive nor dead, has unexpectedly and forcefully interrupted human affairs as we used to know them. Practices of masking, isolating and social distancing have interrupted the automatisms of the status quo, the great machinery of our quotidian habits. What better time to reflect upon who we are and our place in the world?

I am going to dwell on two somewhat radical—in the sense of ‘outside of the norm’—ideas. First, I am going to suggest that masking is a fundamental aspect of modern societies that depend on and embody the drama of exploitation and violence. Second, I am going to suggest that we, as subjects-in-becoming, are conditioned to partake in sustained practices of masking in order to embody the myth of a stable and separate (read: fixed and autonomous) Self. I’ll ground this reflection in my situated knowledge as an androgynous lesbian, settler-refugee-turned-immigrant Canadian from Bosnia and Herzegovina, born in ex-Yugoslavia under its communist benevolent dictator, Tito, before spending five years across three countries as a war refugee. I fled the Siege of Sarajevo at the start of the 1992-1994 Balkan War, whose purpose was to wipe clean the Balkans of its “Muslim Problem.” I was seven years old when the genocide exploded; my family happened to be of Bosniak Muslim heritage because some 600 years ago, my ancestors were violently converted to Islam by the Ottoman Empire. In 1992, we were forced into exile, first in Croatia, then Switzerland by way of Italy. I say I was a “refugee” because it’s a recognizable political category; in fact, my family did not have the privilege of even that precarious legal status. Legally, we were “temporary guests,” forced to reapply for papers on a yearly basis. Finally, by 1997, my parents had had enough. Alongside their children, they were accepted into Canada as landed immigrants.

This reflection about wearing masks is not mere theory; it’s grounded in the trauma of lived experience.

Masks perform certain functions. To mask is to hide, to play a part, to obscure. When I was growing up in communist Yugoslavia, one of its major ‘Socialist Republics’ was Bosnia and Herzegovina. It was primarily comprised of Muslim Bosniaks. The rest of its population was split between Orthodox Serb Bosnians and Catholic Croat Bosnians, and to a smaller extent, Roma people (including a tiny Jewish population, although most had fled during and following WWII). Tito was crowned by the West as Yugoslavia’s “benevolent dictator,” an oxymorons title that masked the lived reality of the country’s highly ethnically fragmented population.

I was not taught to be a good Muslim girl; rather, I was taught to be a good Communist, which demanded that I erase my Muslim cultural heritage, its beliefs and rituals. Tito’s Yugoslavia thrived and survived for more than thirty years because of masking. Its nationalism demanded a kind of unity that necessitated its Muslim population embrace Western secularism and modernism. My parents, children of Muslim peasants, were schooled to think of Ottoman Turks and Islam in barbarian terms only, to think of their religion as inferior to the two dominant and Western others: Catholic and Orthodox. They were not taught to think critically and deconstruct religious dogma in general, but rather, to be ashamed of their Muslim difference. This was cemented in me as well, because the mask worn by ex-Yugoslavians was coloured by the erasure of ethnic and religious differences. Identity had to be formed along national lines, and plural, intersectional or hybrid expressions of the Self were neither desirable, nor could they easily flourish under such circumstances.

The mask came off with the start of the Balkan War. Slovenia was wealthy enough and had economic and military support from Austria to leave Yugoslavia. Croatia, too, was wealthy and allied enough to leave the dying communist country. But when Bosnian and Herzegovina voted for Independence, all hell broke loose. The then Corian and Serbian presidents met in private and decided to rid the Balkans of its “Muslim Problem,” and, while they were at it, split the country in two: Bosnia would go to the Serbs and Herzegovina to the Croats. The genocide began, as did the wearing of new masks.

If the masking in ex-Yugoslavia had been the myth that we were all the same, all good communists, the masking during the genocide was different: now those of us with Muslim names had to wear the mask of our religious heritage. It didn’t matter that two generations (my parents and me) had been taught to dislike and fear Islam. It didn’t matter that we had been thoroughly secularized and therefore no longer practiced our religion. We had to wear the mask of Islam. It justified the bullets aimed for us. It made possible the killings, rapes and forced exiles.

That our identities are socially constructed was obvious to me even before I could put the experience of this phenomenon into words.

Whether they want it to or not, children of war become intimate with violence and terror. As an undocumented body in Croatia (then Italy), I learned to blend in and assimilate. I wore the mask of normalcy, hiding my trauma. After crossing the Swiss border illegally, my mother and her two children were given the right to stay as “temporary guests.” We learned French, went to school, and began to wear the mask of locals. I suffered from extreme and constant migraines, PTSD symptoms, anxiety and depression, but went to school and got straight As, hiding as best as I could my feelings of alienation from the other children. Our legal status put us in an extended and extremely precarious economic situation—one that was untenable. The crippling poverty was a source of shame, and I wore the mask of the good, quiet girl so that nobody could see the anger and pain that haunted me.

When we came to Canada in search of a better life, I wore the mask of the grateful and happy immigrant until my PTSD symptoms made it difficult for me to function, and I had to seek professional help. I tried my best to embody the neoliberal ideal by chasing a well-paying career as a writer in the cultural sector, but that meant ignoring toxic work environments where bullying was the norm. Finally, I quit the rat race and went back to university to pursue a multidisciplinary PhD that looks at the intersections of cultural production and ecological and social violence. When it became evident that I was a settler-immigrant rebuilding my life for the nth time in a country founded on colonial violence, on genocide, it became hard to wear the mask of the happy Canadian citizen.

Rewinding a little, as an adolescent growing up in Canada, I was susceptible to the social norms that created my self-in-becoming. I learned to wear the mask of the happy consumer, waiting in line to get the latest iPod—remember those? Then there was the iPad, iPhone, MacBook, and so on, in a fast-changing technological cycle that obscured (and still obscures) a toxic and deadly transnational network of e-waste. In short, my transition from ex-Yugoslavia to Canada can be summed up as going from being good communist to becoming a good consumer.

As I began my first university degree in Commerce, education was not related to the joy of learning or the discomfort of intellectual and spiritual growth but became a means to an end. For social status and economic power, I traded my time, energy and my health. I landed my first job and worked long hours, going from one toxic work environment to another to reach milestones that never fully satisfied me: condo, car, gadgets, vacations, and so on. The pursuit of all these material things and social markers of success masked a deep void.

The shock of finding myself attracted to women interrupted what otherwise might have been the good life I’d been watching on television screens since I was a kid. I let women into my heart, and this difference was harder to mask than others. I was a lesbian. Closeted at first, of course, since the heterosexual social norm (heteronormativity) forced one into a series of endless coming outs that will not end until gender and sexual diversity become the norm. Or: when the absence of sexual and gender hierarchies will mean the absence of social norms. It gets better over time as some famous LGBTQ+ celebrities rightfully tell us—but coming out never stops because heterosexuality remains the norm.

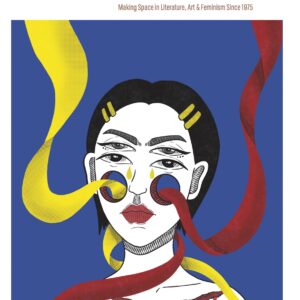

Heteronormativity not only regulates which sexual acts are deemed as “normal” and “natural,” and by extension, which ones are deemed as “deviant” or “other,” but it also regulates the Western European gender binary, masculine and feminine. My poem, “Androgynous Beauty,” resists sexual and gender norms, while also resisting English as the dominant language of poetry:

Everyone outside of heteronormativity’s framework is forced into a closet, then into performing coming out ceremonies, however grandiose or banal. But heteronormativity is liberal and expandable. It has allowed gay and lesbian monogamous couples with children into its social fabric. Following this line of logic, we find ourselves in a homonormative nation state that presents itself as benevolent and diverse, while pinkwashing hetero- and homonormativity, systemic racism and sexism, and putting under the rug oppression and exploitation of human and other-than-human bodies.

Because that is the price we pay when we wear masks: we hide, obscure, pinkwash and cloak violence.

My whole life I have been taught how to wear some masks, forced into others, and masked myself for the sake of survival and ultimately, out of force of habit. When I come out as a lesbian, I experienced the pain and dangers associated with truth-telling, with affirming a subject position outside of the dominant norm. It wasn’t until I had my son that I began a process of unlearning that precipitated fundamental shifts in my perceptions and ways of being.

I am the non-biological mother of my child who was conceived with the help of an anonymous sperm donor. The biological mother was automatically legitimized as the mother on the birth certificate while my name was left to the “father/other parent” line. School staff constantly sought to find a father figure for my child, forcing us into a heteronormative framework. My poem, “(M)other,” attests to this experience of erasure as the legitimate second mother of my son:

Caption: “(M)other” was shortlisted for the 2018 CBC Poetry Prize and has since been converted into a children’s story. The short film was co-directed and animated by Ambivalently Yours.

“(M)other” ends with me wearing a mask—the mask of Star Wars character, Padme Amidala, a peace-loving Queen. The poem ends on a lighter note, a conciliatory tone, because I understand how heteronormativity forms us as subjects-in-becoming, and this insight gives me the compassion and energy to keep educating and fighting for my rights as the legitimate other mother of my child. It’s still a mask, however, because underneath the peace offerings, there is a wounded self that is still working towards healing the macro and micro-aggressions resulting from heteronormative institutions and individuals who have not yet understood the ways in which their discourses and behaviours are produced by social norms that other, oppress and harm me and my family.

Yet, the mask of Padme Amidala is a mask I am consciously choosing to wear, just as I am intentionally wearing a mask to protect myself and my community from the spread of COVID-19. The mask of nationalism, religion, heteronormativity and consumerism were masks imposed on me. I was not even aware of them or how they constituted a particular sense of self. The mask of Padme Amidala represents a conscious desire to look for a stronger, peace-building aspect of myself while being fully aware of the violence and suffering within and around me.

The birth of my son was a shock; an illumination. It made me realize that bloodlines and DNA aren’t what constitute a family. Rather, it’s by embodying an ethic of care, by being responsible for another’s wellbeing, that one establishes kinship relations. Fully integrating this insight allowed me to extend my circle of kinship to other-than-humans. I have always formed powerful bonds with trees and plants. People from Bosnia & Herzegovina understand themselves as infused with mountain consciousness. Since our Balkan lands are all hills, rivers, valleys and mountainous ranges hugged by the Mediterranean to the West, it makes geographical and cultural sense. It’s my intergenerational love and sense of respect, responsibility and reciprocity with the land that has made our forced exile all the more painful and disorienting.

Extending care and kinship relations to other-than-humans led me to chose to wear another mask, a more-than-human “Mossification” self-in-becoming:

Caption: “Mossification” a triptych photograph of a more-than-human self taken by Nicole Crosier, 2018.

When I say more-than-human, what I mean is that I have come to understand that I am not a singular, separate, and autonomous self. The hyper-individualism of the West is good for business. . .it favours the American dream of progress and power: social status and financial success. The myth is that if you work hard, you’ll accumulate these late capitalist ideals and be happy. It favours hyper-consumerism. But this dream is not only unsustainable for the planet, which is under a huge ecological stress in the form of climate change, mass species extinctions, high ocean acidification levels, but it is also unsustainable for many humans, especially those living in precarious conditions, working in sweatshops or getting sick by informally collecting our e-waste, the toxic and hidden side of the neoliberal dream.

Who “I” am is entangled with a host of others, not just other humans and their stories, transnational production processes, institutions of power, but also clusters of other-than-humans, including other animals, bodies of water, lands, and even inorganic elements such as viruses. “I” am vulnerable and plural because the border of my skin is porous and because in my psyche are lodged the thoughts and ideas of others. There is never a moment in which “I” is singular even though the pronoun creates the illusion of independence. Nothing has taught us that better than COVID-19, with its rapid and fluid movement between borders (countries and bodily borders). The very presence of the virus is a collapse of borders because it is neither life nor nonlife. In the West, the borders between Life/Nonlife or Being/Nonbeing mean big money since they legitimize harmful extraction processes of land and minerals, as well as harmful pollution practices into bodies of water. While we have animal rights, we have yet to think of a framework for rock rights since they’re deemed nonlife.

And yet: we are materially entangled with everything, from mushroom to crystal. Polluting over there finds its way back to us, even if unequally (the global South and marginalized folk pay for ecological violence, pollution and climate change disproportionately). That is why, beyond more-than-human entanglements with organic beings, I am reconceptualizing myself into a plural and porous self with organic and inorganic matter, all of whom enter the fabric of my material-psychic plural and porous self.

Caption: “More-than-Human Sanita Fejzić” by Mathieu Laca, oil on linen, 92 x 122 cm, 2018, featuring the writer enmeshed with fungi and crystals.

In this portrait of a more-than-human me, no masking is needed. The face, so essential to Western portraiture and its obsession with the individual, bursts open and blurs the boundary between inner and outer, self and other, human and nonhuman. Crystals and fungi are a part of my body because we are enmeshed with the stuff of our world. That may be the greatest unmasking yet. The greatest collapsing of borders was not the fall of Yugoslavia, although that may have been the first and most violent of my life.

When the borders between you/me, same/other, human/other-than-human began to collapse, “I” was not only burst open and humbled, but I also reconnected with a deep and urgent sense of responsibility for the well-being and flourishing of all.