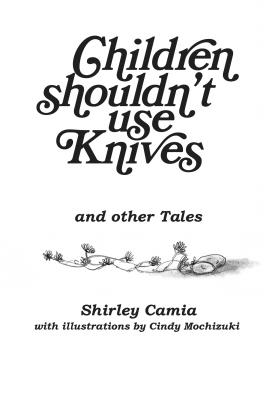

Children Shouldn’t Use Knives and Other Tales shreds the yellow ribbons of childhood sentimentality and, instead, offers an exploration of what it feels like to be small and vulnerable in a stormy world.

I’m not nostalgic for childhood. Childhood was terrifying—the lack of agency, the grownup world’s opaque set of rules, the playground’s ferocious pecking order, the fear of real and imaginary things. And so I’m grateful that Shirley Camia’s Children Shouldn’t Use Knives and Other Tales shreds the yellow ribbons of childhood sentimentality and, instead, offers an exploration of what it feels like to be small and vulnerable in a stormy world.

Children Shouldn’t Use Knives is a collection that integrates moody poetic fragments by Camia with elusive sketches of telescopes, book stacks, flower garlands, and children draped behind blankets by Cindy Mochizuki. Quotations from nursery rhymes and beloved children’s authors—including Dr. Seuss, Roald Dahl, E.B. White, Judy Blume and so on—open each of the eleven sections, anchoring Camia’s work with familiar wisdom that illuminates the ominous facets of youth. Camia’s original poems and Mochizuki’s complementary illustrations conspire with the famous authors’ quotations to create a shadowy, dreamy atmosphere.

Children Shouldn’t Use Knives acknowledges the dangers and threats that haunt children beyond the realms of nightmares and classic scary fairy tales. For example, “In the Spring” does away with stereotypical optimistic associations with the season:

what defences

does a young

girl haveas anger

barrels downthe muzzle of a gun

Mochizuki’s illustration of a young child kneeling and holding an unidentifiable implement takes on a dark valence to accompany Camia’s brusque poem.

Similarly, “Life’s Lessons” evokes with a few short lines a difficult story about a child lying about the whereabouts of her uncle:

No, I don’t know where he is.

what she said

to the men

at the door

Camia peddles in subtle ambiances rather than ornate descriptions and so the slight poems tremble while casting long and enigmatic silhouettes—the collection is a shadow puppet show where small hand gestures become animated monsters. While Children Shouldn’t Use Knives recalls Edward Gorey’s Victorian-inspired gothic The Gashlycrumb Tinies, Camia’s playground of lost children is softer and more modern.

With only eleven brief poems, the collection is very short. While I appreciated Camia’s invocation of well-known children’s literary authors who don’t shy away from the confusion and trouble of childhood, I did find the extracts drowned out Camia’s own voice at times—they were often as long as the poems themselves. I found I wanted a few more poetic moods from Camia. I wanted to inhabit her and Mochizuki’s beautiful, sombre world for a few more beats—just like when I was a child and I couldn’t stand having a story come to an end.