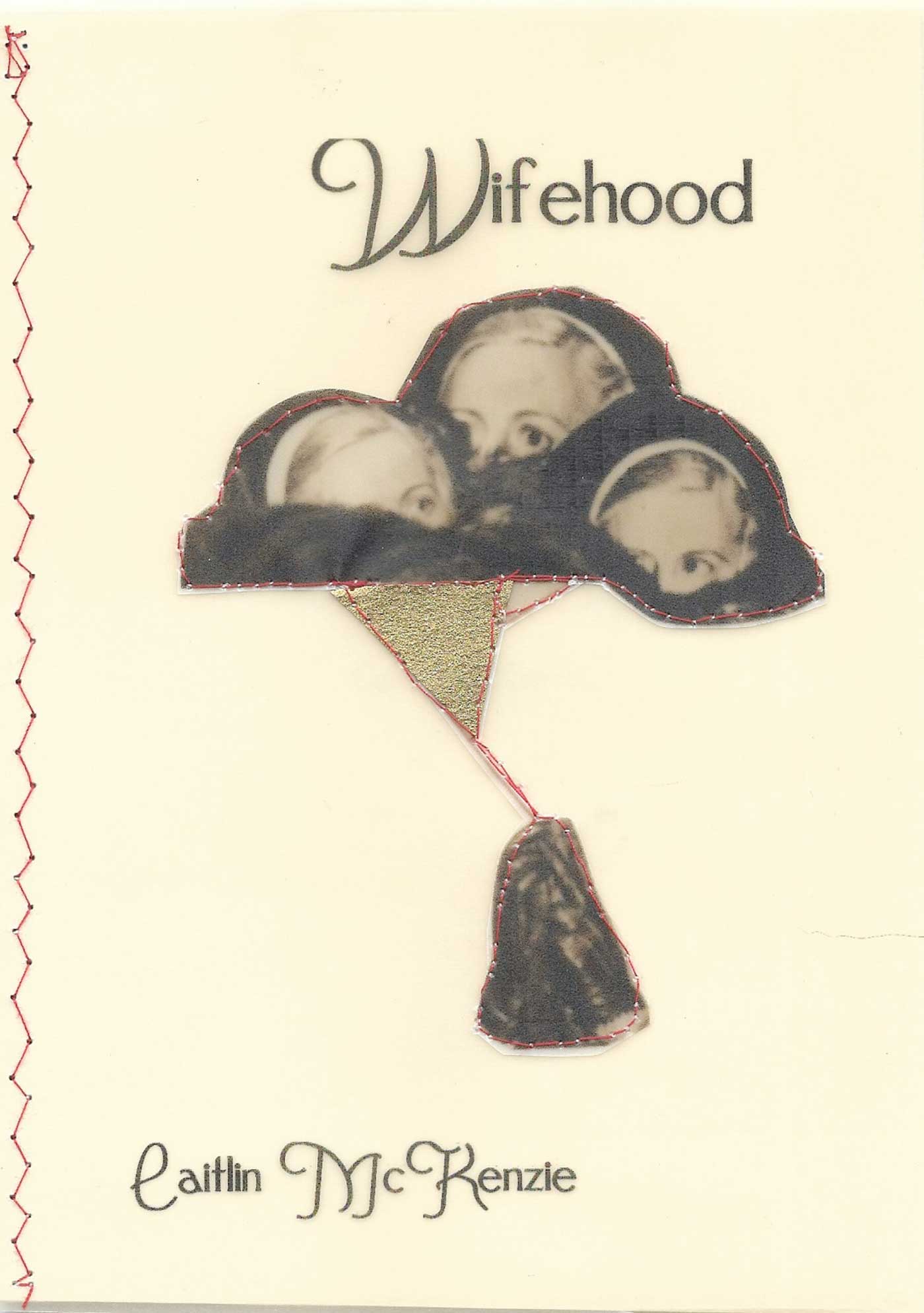

Wifehood

Wifehood

by Caitlin McKenzie

Ethel Micropress

32 pages

$10

Deceptively simple, beautifully balanced, and structurally near-infinite: Barrie, Ontario poet Caitlin McKenzie’s first chapbook charts what it means to be a wife after growing up within a shattered parental marriage by recentering the women who married famous men back into their own stories. It’s an apt combination of theme and physicality from Ethel Micropress, whose hand-sewn chapbooks—complete with intricate fabric-and-thread embroidered covers—build in extra resonance for a book delving into what wife means. With a painter’s deliberate eye and an origami-like sense of context, McKenzie delivers a debut chapbook that’s intimate and structurally deliberate, full of poems whose packed references barely ripple their surfaces.

Over sixteen short poems organized into five movements—each section framed by deeply personal prose pieces and photo-collage art—Camille Monet’s deathbed portrait blurs into her cooling body, June Carter speaks about silence, and Hemingway’s four wives slowly move from passivity into their own power in ways that, at least on the surface, call back to Atwood’s Penelopiad and Madeline Miller’s Circe.

But Wifehood’s direct, unadorned testimonies quickly unfold into murkier, more organic territory through their supposedly simple lines. Monet’s purported objectification into a painting on the wall transfigures in one line into an anguished grief offering from one lover to another. Clementine Churchill languishes as “greatness / strangled in petticoats” even as she’s “become the tamer of a mans / Black hound moods”—with all the conflict, disappointment, power, and ultimately tenderness that single line embodies. Beneath McKenzie’s streamlined language is a carefully calibrated machine of deliberation, pulling wordplay, historical references, and a masterful grasp of how lines balance into deeper readings of her subjects’ complexities and choices. Wifehood is less interested in counting scars than a restless, emotionally courageous search for better answers.

As the prose pieces recount her narrator’s growth from an abuse-spurred horror of marriage to a way of loving that redeems it, the route through McKenzie’s sparse, slender portraits comes to feel like the intimate insides of a thought process—how we divine the world from the very few words other women leave us; the fumbling setbacks, joys, and satisfaction of finding one’s very personal way from there to here.

But along the path, it’s how Wifehood uses details of its subjects’ lives that takes it from personal to profound. McKenzie’s economical, dense nests of historical reference—each fact meaningful—give something back to the women she’s spoken for, actively inviting readers to find the rest of their stories.

It’s a rare collection that models so neatly the action it describes learning: to seek context, reciprocate humanity, learn to see others clearer; a celebration of the joy waiting if we only read past surfaces in marriage, in people, in life.