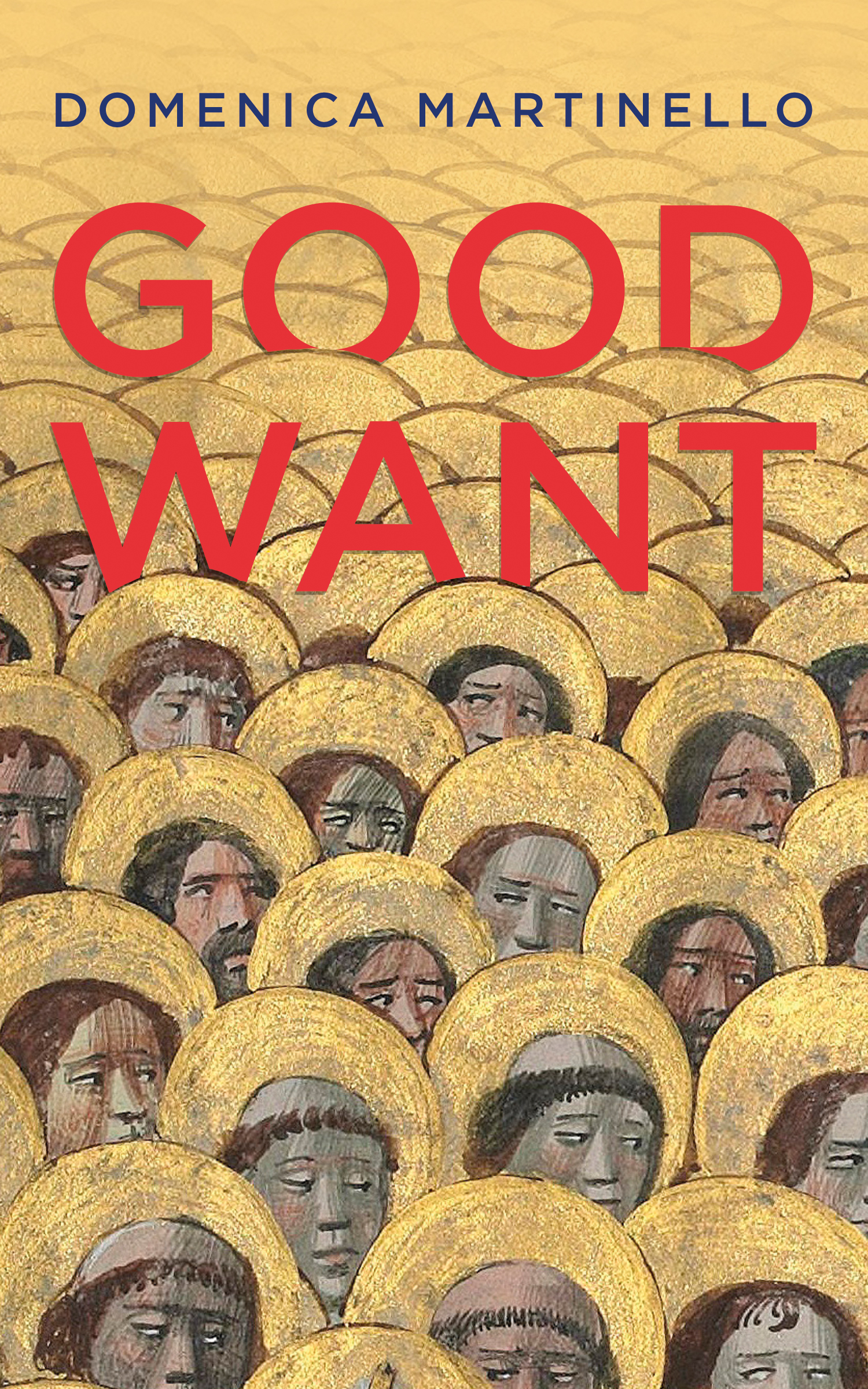

Good Want

by Domenica Martinello

Coach House Books

109 pages

$24

Domenica Martinello’s Good Want lies in the chasms separating good from bad, speech from silence, and faith from disbelief, producing a meditative collection of poems that gets to the core of desire as a human condition. Divided into four sections, this second collection from the Montreal-based poet moves readers through candid, witty poems that unearth desire from the burdens of social expectations, intergenerational trauma, and theoretical complexities.

In Good Want, to “desire” anything is to feel the lack of it. For Martinello’s speaker who wants many things, this liminal space is not only creatively powerful, but deeply intimate. From the largerthan-life, utopian longings for a world that does more, to the fondness for everyday items like spandex, the desire expressed in Good Want is quotidian, expansive, and even imaginative. To encounter desire again and again, albeit in different forms, accentuates a feeling of lack until the very act of wanting something becomes the desire itself: “Waste not, want not. Waste not your wanting. / We want more of everything.” What’s being expressed here is not so much greed, but a solemn acknowledgment of the impossibility to fulfill certain desires. An example is the author’s desire to protect her mother from childhood neglect: “I want to bake my mom / into an apple pie / to keep her safe.” This shift from realism to imagination is quintessential of how desire creates turns in Martinello’s poems, generating a constant curiosity about the paths where desire may lead.

In this transformative space of Martinello’s wanting, desire and goodness chase each other in a cat-and-mouse game. Like the deconstruction of desire, the “good” in this collection is multidimensional; it indicates pleasure, morality, but also platitudes. The good is also the desirable, but Good Want questions whether desire itself is good. As definitions of the “good” become muddled, these poems also ask: what good is it to desire to be good? While these questions remain largely rhetorical, Martinello’s search for other ways of contemplation and expression is refreshing: “I’m just so tired of trying to be meaningful / I just want to say nothing / but throw some weight behind it.” This loss of faith in the meaningful is another one of Good Want’s repeating themes, one that puts forth the everyday, the mundane, as an avenue to recreate meaning.

Good Want shows that the simple act of wanting or liking something is an undeniably human quality, and there is a deeply comforting feeling that comes from reading about it. Charming, original, and sincere, Martinello delivers a collection that challenges our ability to hear silences and speak simply.