Therese Estacion

Book*hug Press

96 pages

$20.00

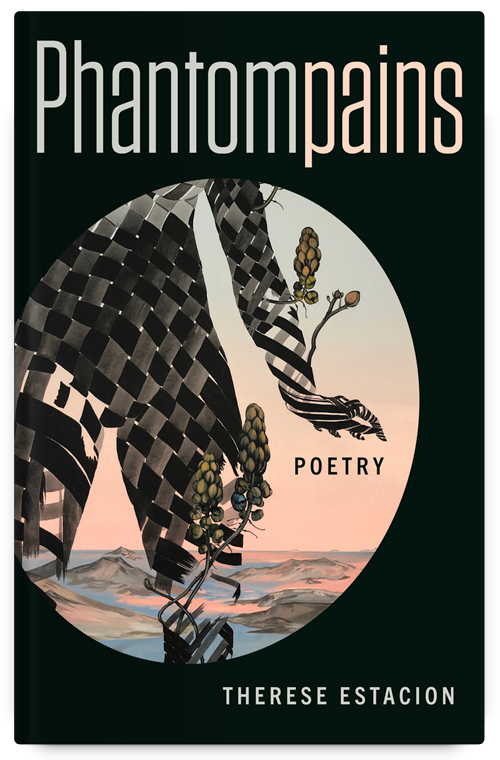

After surviving a rare bacterial infection that took several of her limbs and organs, Therese Estacion embarks on a journey to search for home, catharsis, and self-love. Her debut poetry collection, Phantompains, explores themes of disability, grief, and mourning—of her former able body, but also her early childhood in the Philippines—as a necessity for recovery and finding peace.

Drawing on Filipino horror and mythology, Estacion turns to monsters, ghosts, and beasts to navigate her personal pain and grief. Mirroring the loss of her own reproductive organs, she weaves in supernatural imagery of The White Lady, who weeps over the “dead uterus lying sadly on a / pillow looking very much like / the burnt pork belly at breakfast no one wants to touch.” Similarly, Estacion envies the shape-shifting female aswang, who possesses the ability to transform and “put herself back together again, FULL.” Despite the aswang being the most feared creatures in Filipino folklore, the poet laments, “I wish I was her / I wish I could put back together my dismembered body.”

As Estacion grapples with her new body, she realizes that her disability has also become a spectacle for the able-bodied gaze—and though the collection may open like a typical fairytale, it’s clear that it’s something more macabre: “Once upon a time the spectacle / a young woman flatlined / herself into oblivion.” Where there are moments of defeat, however, there are also moments of victory—most notably in “The ABG” when Estacion boldly subverts the spectator’s gaze both through her creative use of language and through the act of being seen.

While monsters are humanized throughout the collection, “The ABG” purposefully reduces the spectator’s identity to the inanimate pronoun “it.” What stands out about this piece is Estacion’s combined use of italics and the unique compounding of words, which are especially powerful in emphasizing the spectator’s relentless, almost stalker-like behaviour: “It follows&follows&follows &watches&watches.” When Estacion prepares to confront the spectator, however, “it” pretends to have been “just minding its own / business all along.” Though it may seem like a small act of defiance, Estacion’s displacement of the spectator’s intrusive stare and calling out of “its” seemingly innocent intentions are symbolic acts of resistance and reasserting her own agency.

Divided into five sections, each chapter of Phantompains is a window into Estacion’s healing process—from using the familiarity of childhood folktales to process a new reality, to finding catharsis in uncovering repressed memories and feelings. She writes that “phantompains are a type of pain you feel even though your limbs are no longer there.” And it may be that the remnants of this loss, like phantompains, may never fully go away—but it’s a start.

—Nadia Siu Van