Many of Thom’s poems deploy this bold, storytelling voice, foregrounding the wisdom of what is said, experienced, lived, rumoured, and gossiped in lieu of traditional history with its myopia of normativity. a place called No Homeland consistently examines the collisions that marginalized identities encounter.

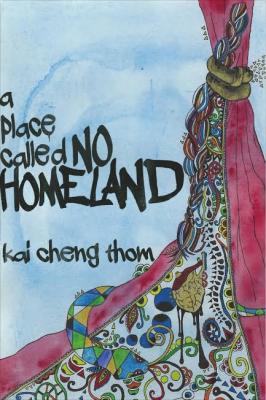

A maternal figure in my life recently wrote me to say she struggles with poetry precisely because it exists as a place between thinking and feeling—a place we’re out of the habit of visiting, let alone dwelling. But then there are some poems that shake you and bring you back to the space that flickers between pathos and logos. Kai Cheng Thom’s a place called No Homeland is the hearth of such a real yet imagined place. These are poems that live with paradox, straddling both myth and reality. In a place called No Homeland, Thom transposes the energy of queer punk spoken word onto the page. The result is a vulnerable, shimmering debut.

A maternal figure in my life recently wrote me to say she struggles with poetry precisely because it exists as a place between thinking and feeling—a place we’re out of the habit of visiting, let alone dwelling. But then there are some poems that shake you and bring you back to the space that flickers between pathos and logos. Kai Cheng Thom’s a place called No Homeland is the hearth of such a real yet imagined place. These are poems that live with paradox, straddling both myth and reality. In a place called No Homeland, Thom transposes the energy of queer punk spoken word onto the page. The result is a vulnerable, shimmering debut.

Throughout the collection, Thom commits to bringing queer, trans, and racialized bodies to the forefront. The inaugural poem, “diaspora babies,” tells us there are “stories that are never told / but known / nonetheless we bake them into bread / fill buns with secrets.” For Thom, these repressed histories endure despite their marginalization. They exist materially and spiritually in unexamined corners and baked into daily bread, nourishing the poet. Later in the poem she writes “some poems / cannot be written / just felt,” inviting us into her poetic (no) home—that space between thinking and feeling. These invocations initiate us into the world of the collection where tales of the oppressed emerge from their “invisible ink” and “ghost children drawing maps in the margins” sing themselves into vibrant existence.

What unfolds in the following poems are new geographies, both difficult and sublime. Thom transforms Vancouver into a “concrete rainforest / sequestered in silence / sea-hungry cavernous” in “downtown beastside,” blending mysticism and grittiness in a way that resonates sincerely with the fraught cityscape. Similarly, “the river” begins with a covert lesson in oral history and geography:

someone told me once

that a secret river flows

under every street

in every chinatown in every city

The poem sprawls beautifully, proceeding gently, at first, with the soothing alliteration:

this river speaks

in a secret language that sounds like

a sigh

and stretches

And then the poem rushes into the rapids of brutal revolution: “darling, when your revolution comes, i will not be here, / when the towers start to burn, i will be the first to die.” Many of Thom’s poems deploy this bold, storytelling voice, foregrounding the wisdom of what is said, experienced, lived, rumoured, and gossiped in lieu of traditional history with its myopia of normativity. a place called No Homeland consistently examines the collisions that marginalized identities encounter. And through this, Thom finds, “there is a poem waiting deep below.”