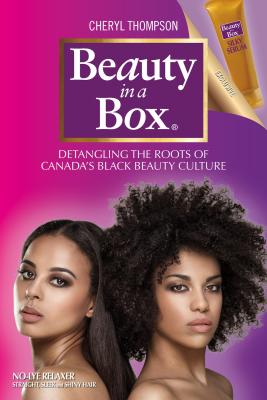

Dr. Cheryl Thompson

Wilfried Laurier University Press, 311 pages, $29.59

2019

In her 1987 essay “Oppressed Hair Puts a Ceiling on the Brain,” writer Alice Walker extolled the beauty of natural hair and ventured that Black women can attain “spiritual liberation” by rejecting straightened, chemically “relaxed” or other hair styles such as extensions or weaves. She later read the piece at a gathering of Black women who sported (mainly) straightened hair.

“You can imagine how that went over,” recalled a woman I later interviewed who attended the event. Fast-forward thirty years and Cheryl Thompson likewise explores the often-charged relationship between Black women and their hair in Beauty in a Box: Detangling the Roots of Canada’s Black Beauty Culture.

“Black hair really is a complicated subject,” asserts Thompson, an assistant professor at Ryerson University who boasts Jamaican-Canadian ancestry. “For many black women it conjures up painful memories of being teased and having their hair combed . . . and in some cases, permanently damaged by poor hair care techniques . . . Our hair is imbued with dual and sometimes conflicting meanings . . . While natural hairstyles like Afros, dreadlocks or cornrows might denote a black woman’s politics, they can also be just . . . her preference, with no political meaning whatsoever.”

With the visage of Viola Desmond now featured on the Canadian $10 bill, readers will find noteworthy Thompson’s in-depth discussion of the Halifax-born 113 beautician whose 1946 removal from a “whites-only” section of a Nova Scotia cinema sparked a historic racial discrimination lawsuit. The author emphasizes the role that African Nova Scotian publisher Carrie Best played in publicizing Desmond’s plight through her widely read periodical, The Clarion. In doing so, Thompson underscores the long-standing links between the Black press and the Black hair care industry. “The newspaper was instrumental . . . in helping [Desmond] hire a lawyer to appeal her conviction, but in the end, her case was dismissed,” Thompson writes.

As for the strategies that Black women have used to “tame” their naturally kinky hair, Thompson offers stunning revelations about a 1980s-era product known as the “Jheri Curl.” “Companies marketed the Jheri Curl as a ‘low-maintenance’ curly style, an alternative to the chemical relaxer,” the author explains. “It was Jheri Redding, a white, Illinois-born farmer turned hair care entrepreneur, who invented the process.” Popular among Black people (of all genders) in Canada and the US, the style fizzled out after Michael Jackson’s Jheri Curl ignited while he was filming a commercial. The singer suffered severe burns on his scalp.

“I wrote this book out of sheer curiosity to know the roots of my own hair care practices and beauty-product choices,” Thompson declares. “From that curiosity came something that can be used to further . . . knowledge about Black Canadian history.”

Juxtaposed against bombshell revelations about Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s penchant for Blackface, Thompson’s scholarly and accessible volume offers valuable reflections on the myriad contours of racism in Canada.