For their tenth wedding anniversary, Robin and Yu’en planned a small gathering at The Peony, the Chinese restaurant at the Imperial Club. Nothing extravagant. The first of October fell on mid-autumn, the fifteenth day of the eighth lunar month, an auspicious day for weddings, reunions and, as it happened, their wedding anniversary. As the seasonal greeting goes, hua hao yue yuan: May your union be round and full as the moon, and beautiful as the blossoming flowers.

Robin was relieved when Yu’en agreed a hotel ballroom was unnecessary, still haunted by the hundred-table, ten-course banquet her in-laws, the Pangs, had thrown for their wedding ten years ago. The Singapore economy was uncertain, the stock market going nowhere, and Robin’s bank had just laid off a hundred employees. Even the Pangs were feeling uneasy, despite their otherwise healthy income from the rows of shop houses they rented, and which Yu’en’s grandfather had the foresight to acquire.

It was thus agreed that a seven-course individually plated dinner at the Chinese restaurant ticked all the boxes: exclusive enough for the in-laws, affordable because they were members, and at equal proximity between her parents and his. She could not believe her luck when the restaurant manager informed them only the small dining room was available. Another family had booked the larger fifty-guest room for their matriarch’s birthday celebration. This meant they could pare back their own guest list—and there was no room for Yu’en’s three sisters and his entire extended family.

But then Candy, the restaurant manager, called up two months before the anniversary: How lucky, the matriarch had passed away and the large dining room was now available. Another family was also making enquiries but Yu’en had asked first; in fact, his mother had dropped by just that morning and spoken to Candy herself. It wasn’t strictly allowed but, for them, she would hold the room, just for one day. Did she want to come down and pay the deposit before someone else snatched it up?

Robin ran through a panoply of excuses in her head, trying to come up with the perfect reason to say no need to change, the small dining room was perfect. But then she thought of Yu’en’s sisters and the things they and his mom would say— no, had already said with their stares at the last family lunch—Doesn’t she know mid-autumn is for family reunions? What kind of wife is she? Poor Yu’en, he should have listened to us.

“I’ll see you tomorrow evening,” she told Candy. As she hung up the phone she realized she had crushed Billy’s letter from school—a consent form to pick up trash along the beach at East Coast Park. Across the table, her nine-year-old son stared aghast, then just as quickly looked down at his homework when their eyes met.

Once an exclusive preserve of British and European expatriates, the Imperial Club had, by the twenty-first century, come to be dominated by Singapore’s old-money Chinese families, most of them British-educated and in some ways just as or even more elitist. The surest sign of their rising clout was The Peony, whose head chef once helmed the finest Cantonese restaurant in Hong Kong. The Peony occupied the bridge hall on the third floor, having earlier evicted its mostly white players to a windowless room in the basement.

Robin and Yu’en had practically grown up at the club, although with their six-year age gap neither had noticed the other. By the time Robin was interested in boys, Yu’en was already studying in London, and on his return she had moved to America. They met, of all places, in Shanghai, where Robin was living and Yu’en visiting for a conference. Perhaps it was the romance of dating in a foreign city that sealed their union: holding hands on the Bund, the future felt as bright and limitless as the dazzling lights of Lujiazui’s skyscrapers across the Huangpu. Only much later did they find out about their Imperial Club connection, which their parents welcomed as icing on the wedding cake.

Robin had not wanted to join the club. It reminded her too much of her parents and a childhood she did not want to remember: countless hours spent at dance, tennis, and deportment classes, feeling inelegant and unwanted behind her pink plastic glasses and rainbow braces. Yu’en, on the other hand, was on the club’s roll of honour for winning the boys’ tennis title three years in a row. If he had known her then he would never have dated her, her mother jibed, a joke Robin never found funny.

She found her people at Berkeley. At the Amoeba store on Telegraph, she befriended a Russian-American guitarist as they both reached for the same Japanese goth record. With him she joined an eclectic assortment of peaceniks, protesting on Sproul Plaza in the day and smoking weed while watching the stars at night. She still remembered her first joint, coughing as she tried to inhale.

Not your first time, is it? Sasha had asked.

No, of course not, she replied, holding the smoke in her mouth.

He took the joint from her, exhaling a trail of enviably perfect-shaped clouds from his pursed lips. Until then, she thought what they had in common would paper over their differences. But the gap between them grew into something bigger than smoke clouds as Sasha and the others chased more and more expensive highs. Something in her recoiled when she watched them snort cocaine in the penthouse of a San Francisco apartment, and though she had wanted so much to be one of them, that night she realized she was just an imposter. As the sun rose over the bay, she walked out of the apartment, leaving Sasha and the group behind.

No one knew what had happened in Berkeley, or at least no one she knew back home. It was her little secret, something she took out and polished like silverware from time to time when she tired of her newly respectable life as an analyst with a leading American bank, first in San Francisco and then in Shanghai. Yu’en, who had studied in London, said little when she asked him about his time there, and asked her nothing about her past. In any case, her time at Berkeley had only been an interlude.

The Imperial Club represented her return to Singapore’s elite—not the ones who ran Singapore, because the government was careful to avoid those ties—but the ones who owned Singapore, though on occasion she felt a stab of proletariat sentimentality when she thought of Sasha. Even so, the longer she remained in Singapore, the less she remembered of America. Every Sunday morning, they joined dozens of other well-heeled members whose kids played in the ionized, heated pool or in the well-monitored playroom while the parents relaxed indoors. Lunch was always at The Peony with the Pang clan, when she sat smiling politely while the relatives gossiped over dim sum, washed down by endless cups of Pu’er. By the time they were done, the weekend would be over.

One week flowed into the next, months into years, and before she knew it they were racing towards their tenth wedding anniversary. As she clutched the table cloth in The Peony one Sunday, tuning out as Yu’en’s sisters talked over one another about their kids, she realized how small her world had become. There had to be more to life than the Imperial Club. She found her thoughts turning to her time in America, forgetting inconvenient details like the contemptuous sneer from Sasha’s blonde ex-girlfriend, who, like all his other high school friends, resided in a grand mansion in the San Francisco hills. Or the time she walked home alone on urine- scented Market Street after Halloween, her make-up streaked by tears. More and more often, the hazy, languorous nights she had spent in the Berkeley hills began to return like the fragrant scent of a pleasant dream, always just out of reach.

She was standing in the club’s lift lobby when a flyer on the noticeboard caught her eye. A black-and-white still of a kopi tiam: tiled floor, monochromatic decor, formica tables. An old man sat hunched over one of the tables, his back to the camera. Above him, a mural of a 1930s Shanghainese singer in a qipao, a mysterious smile on her face. Robin stood transfixed as her phone buzzed. She knew it was Yu’en, asking her to hurry. Ripping the flyer from the noticeboard, she stuffed it in her bag and hurried to The Peony.

“Mrs. Pang came by already this morning,” Candy said in Malaysian-accented Cantonese, informing them that his mother had already paid the deposit. The only thing left was to decide on the menu.

“She suggested the longevity menu,” she said, pushing a sheet of paper across the table, the dishes all named after popular wedding greetings like Eternal Sky Endless Earth and House Brimming with Gold and Jade.

Robin’s thoughts drifted back to the Lonely Hearts flyer. The singer’s gaze beckoned, as if a secret lay behind her lips. Below the photo was a quote:

‘Deep down, all the while, she was waiting for something to happen.’

The Lonely Hearts

Every Friday, 7 p.m.

Cavenagh Bridge

Briefly, she thought of herself as the woman in the mural, something concealed in her smile. But as she sat in The Peony, listening to Candy describe each dish in agonizing detail, she realised she had more in common with the hunched old man. The woman’s eyes taunted her: Look at you and your pathetic life. You don’t even do anything about it. No wonder you feel so wretched.

“What do you think?” Yu’en’s voice brought her back to the present. “I think we should offer guests both choices.”

Robin blinked. What was he asking?

Candy repeated her question: for dessert, should they go with almond cream or lily bulb soup?

Almost immediately she remembered her mother’s words at their wedding: bai he or lily bulb, also meant a hundred unions, meaning the couple would remain together for a hundred years.

“Sure,” she said. “Let’s give them a choice.”

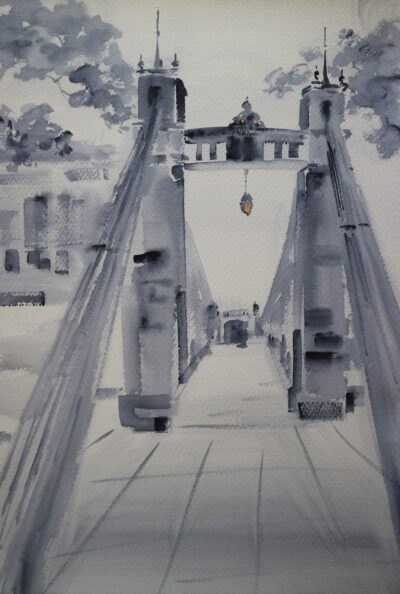

Watercolour painting by Singaporean artist Aaron Gan, entitled Cavenagh Bridge

Cavenagh Bridge linked the civic district on the north bank to Raffles Place, the main commercial district, to the south. Although the bridge was right below Robin’s office, she had never paid it any notice. Holding the folded flyer in her pocket, she strolled towards the bridge. It was crowded with tourists taking photos of the skyline, and office workers on their way to Boat Quay for drinks.

Even from a distance, the petite woman in a yellow dress caught her attention. She stood at the centre of the bridge, her skirt billowing in the wind. Like a magnet collecting iron dust, the oddest array of characters began to gather around her: an unshaven young man wearing a football jersey over his work trousers; a greying retiree clutching a cloth bag with what looked like a fishing rod sticking out; an Indonesian tai tai with big hair and an even larger Birkin; even a Japanese tourist, with a pair of binoculars around his neck.

Robin stepped closer, about to ask if this was the Lonely Hearts gathering, then stopped, surprised by the silence. No one spoke, as though they understood each other without communicating. The woman in the yellow dress greeted everyone, acknowledging their presence with a smile, a nod of the head. Then, without warning, she turned and walked in the direction of Marina Bay. One by one, everyone followed until Robin was the only one left standing on the bridge. She hesitated, then ran after them.

They ended up on a long, rambling walk, travelling down underpasses and over more bridges as they headed deep into the civic district. Everyone was busy observing every little thing around them, no one said a word. Alone, Robin began to notice the details of graffiti, the sound of traffic in the distance, the occasional wet crunch of grass under her heels. They ended up at the Padang, where she followed the group onto the middle of the lawn. The woman in the yellow dress gathered her skirt to sit on the grass, gesturing for the others to do the same. Robin settled on the grass, hugging her knees. In the clear night sky she recognized Mars, orange and unblinking.

“Mars,” she heard herself whispering.

“Venus,” a male voice replied.

But no one was talking to her. That was when she saw the Japanese man a few feet away, lying flat on his back, staring at the sky through his binoculars.

“But it’s orange…” she said, her voice drawing the attention of the group.

The woman in the yellow dress placed one finger to her lips. Robin bowed her head in apology. One by one, everyone in the group seemed to fall into a deep, meditative state. Next to her, the man put down his binoculars, his eyes still on the sky. She copied him, hands cradling the back of her head. At first she saw nothing, only the dazzling flare of street lights. But then something odd happened. The longer she stared at the stars, the brighter they became. In that moment she was nineteen again, gazing at the stars in the Berkeley hills, the smell of weed in the air. Back then with Sasha and the crew, now with a group of oddballs. She closed her eyes. The sound of cars faded, everything faded, even her heartbeat. She was the grass tickling her neck, the sky and the earth, the moon above, the stars blinking and shining.

When she opened her eyes, the woman in the yellow dress was already standing. One by one she said goodbye to each of them, hands clasped, bowed Thai-style. Robin bowed in return, and followed the slow drip of members headed towards the train station. The Japanese guy was just behind her, and she stopped, thinking he might say something, but he just nodded and walked past her, disappearing into the crowd of commuters.

Yu’en was already snoring in bed when she returned home. He had been to a charity dinner and made no comment on her absence, only a text to remind her about his grandfather’s remembrance dinner that weekend. How many times did the Pangs have to see each other every month? When they first married she had gone for every birthday, remembrance ceremony, anniversary. But by the second or third year she began to sigh each time Yu’en told her to put something new on her calendar, and what initially seemed like kind words from his sisters and aunts became uninformed opinions and unwanted advice.

“They’re close,” Yu’en would say, whenever she made any comment. “Is there anything wrong with that?”

She got into bed, stared at his sleeping back, then moved closer, hugging him around the waist. An unfamiliar need stirred deep within her. Sex had never been easy between them. Billy had taken a long time—delayed, in her opinion, by her mother and sisters-in-laws’ overeager tips. Did she really need to know that Yu’en’s eldest sister had leaned on a bolster with her legs in the air to conceive Isaac, her third child and first son? But after she had Billy something in her body changed, or perhaps it was too many rounds of scheduled sex that had taken the joy out of the act. The less they had sex, the less they wanted to have sex. Soon it was months before they touched each other intimately, and when they did it felt foreign and uncomfortable.

But the force of her desire took her by surprise now, as did the fact that she was thinking about the man with the binoculars, asking with his eyes if he could get to know her better, only he had Sasha’s face, the same longing look in his eyes as his hand moved down her hip until panicked, she stopped him, too shy to say she wanted him, too, just not this way. Yu’en’s tractor snoring called her back to reality. She stroked the softness of his belly under his shirt, trying to ignore the smell of cigarette smoke and alcohol in his hair.

“What are you doing?” Yu’en stirred.

She said nothing, trying to continue, but he caught her hand. She leaned back in bed, heart pounding, her face hot.

“I’m sleeping.”

As a young child—she had been maybe nine or ten—she had gone to look for her mother one evening, only to hear peculiar, unrecognizable sounds from behind the door, as though Ma was in pain. Ma was often in pain, something she tried to mask like the cognac she hid in her bathroom vanity. She had watched Ma over dinner, wanting to ask if she was okay, but then the phone rang, Ma ordering her to answer.

“Tell your father we made popiah,” Ma said.

It was his favourite.

“Can you tell your mom I’ll be late?” Pa said. “I won’t have dinner at home.”

“But we made popiah,” she said, hoping if she could get the words out fast enough he would change his mind. But Pa said nothing, and over the line she heard him exhale. He hung up without saying goodbye.

Robin closed her eyes and listened to the quiet hum of the air-conditioner, Yu’en’s rhythmic snoring. Her mother’s loneliness, her behavior around her father, her insecurity—all of it came hurtling back through time, pressing her further and further into a bed from which she could not escape.

Was it the fourth or fifth Friday when Yu’en first noticed?

What had he asked? Something about it being a clear night, and had she seen the moon? It was a perfectly innocent question, but there was just something about the way he asked. But how could she explain the Lonely Hearts? A meditation club? A walking club? Every week they went somewhere different, but always they just walked. They walked and walked until the moon was high in the sky, and then they went home. She didn’t even know their names and so gave them nicknames: Tinkerbell for the woman in the yellow sundress; the Astronomer for the man with the binoculars; Megawati for the Indonesian tai tai; Garang Kuni for the retiree who always seemed to have something recycled in his bag. In the one or two hours they spent together it was as if they became something greater than the sum of themselves, but always, they remained complete strangers.

Who was behind the Lonely Hearts? How had that flyer appeared on the noticeboard? She reached in her bag, wanting to check if it had received the Imperial Club’s official chop. But the flyer was not there. Across the bedroom, Yu’en was sitting up in bed, reading the news on his phone.

“Did you take anything from my bag?”

“No.” He glanced at her as she continued searching the papers on her desk. “How many times have I told you? Put your things back in the same place. What are you looking for?”

“Nothing,” she said, moving to the books on her bedside table. Her suspicion grew as she saw Yu’en watching her from the corner of his eye.

“Where were you tonight?” he asked. “Sam was waiting for you to read that Chang’er on the moon story.”

You could have read it to her, she wanted to say, but held her tongue.

“I’ll read it tomorrow,” she said.

The flyer nowhere to be found, she sat on the bed, her back to him.

“Yumin’s husband is back from London,” he said, breaking the silence.

Yumin, his second sister, was married to an Englishman whose hair was as stubborn as his personality. They were either fighting or thousands of miles apart. Which one she couldn’t keep track.

“You need to add him to the guest list.”

“Why don’t you do it?” She glared at him, surprise falling over his face.

“Sure. But you’re the one planning the party.”

“I don’t even want the party!”

An unfamiliar sense of relief washed over her as her words took flight, found their own freedom, and struck Yu’en in the chest. His face crumpled, as if she had said she didn’t want him instead of the party, and all of a sudden she saw with shocking clarity how she had remained in their marriage for so long: it was far easier to go to bed and wake up the next morning pretending nothing had happened and everything was fine, than to walk out the door.

Friday, the first of October. The date she had dreaded for weeks was here. Her purple silk dress hung from the back of her office door, matching patent heels under her desk. On her computer screen was the seating plan Yu’en had sent to the restaurant, annotated with dietary preferences and menu choices in his scrupulously neat handwriting. She closed the window and returned to her inbox, but the thought of forcing herself to smile next to Yu’en, receiving everyone’s congratulations like a blushing bride, threw her into a panic. Resting her head in her hands, she massaged her temples. Then she grabbed her handbag and left the office.

Cavenagh Bridge was lit up in neon purple, the moon looming low over the river in the Prussian blue sky. Everyone was already there. Robin turned her phone to silent but it continued vibrating as they boarded a bus down Nicoll Highway, buzzing again when they got off at Katong and crossed the highway to East Coast Park. The air was thick with the smell of the sea, the fronds of beach palms rustling in the breeze. Her phone buzzed again, the latest message: What happened to you? Everyone is waiting for you to start.

She stood there for a moment, breathing in the salty air, the wind ruffling her hair. What had happened to her? Her, a forty-two-year-old woman, escaping her own wedding anniversary? She knew then—there was no way things could continue as they had.

She turned her phone off and joined the rest of the group at the breakwater. The Astronomer was waiting for her, extending his hand as she approached, helping her onto the rocks. Under their feet the waves crashed, the sea spray soaking her trousers. Far ashore, ships at anchor cast pools of golden light into the black sea. Behind wispy clouds the moon watched them, its reflection rippling in the water. The stillness amplified the voice in her head: What did Yu’en even do wrong? She swallowed, fighting the hot ball of tension rising up her chest. But how can you go on like this? A warm hand touched her shoulder, and the first tear escaped.

One by one the Lonely Hearts stood up from the breakwater, reabsorbed into the city as they crossed the beach. Megawati remained by her side, her hand on her shoulder. The Astronomer watched her from a distance. Climbing down from the breakwater, Robin started walking along the beach. For a brief moment she thought of Yu’en. They were probably finishing up at The Peony, her absence mocked but eventually forgotten. Yu’en had probably retreated to some corner of the club, not one to show others his pain. But he would have returned to the restaurant—he was first and foremost a Pang, with or without her.

Megawati and the Astronomer continued to trail her from a distance. “I’m fine,” she said, using the last bit of energy left in her to smile. “I just want to be alone.” They lingered for another moment, Megawati leaving first. The Astronomer stopped following but remained standing, watching her like a star traveling across the night sky. On and on Robin walked, until the beach became grass and the tide, as though exhausted, stopped charging at the shore.