The first emotion I remember feeling was anger. Then anxiety. Then determination. I was in Toronto, attending a concert with a friend I had met online years earlier. It was the first time that we had occupied a public space together in person; the first time I could really see the ways that she navigated life as a legally blind person. The few hours that we had spent together, seeing our favourite musician in concert, had been amazing, but exhausting for both of us as we had to maneuver our way through spaces filled with people who did not operate in the world the same way that we do.

One moment in particular set me off: we were trying to get home as our physical and mental acuities had grown increasingly weary after the excitement of the show. I was trying to help my friend find her train, which was an extremely difficult task given the impenetrable mess that Torontonians know as Union Station. I was shocked by the number of people we asked who did not know how to help us, or chose not to help us. Even more troubling was the fact that there were no signs that I, as a sighted person, could find that pointed in the correct direction, let alone any means that were accessible enough for my friend to figure out where we were going. Although I had definitely been aware of the numerous obstacles that disabled people face on a daily basis, it had never been this clear to me how much the public world does not welcome those who do not fit the mold of an able-bodied, neurotypical person.

Disability has always been a part of my life, whether it be through my own personal struggles or bearing witness to the struggles of those around me. I was diagnosed with mild cerebral palsy (spastic hemiplegia) at a young age, having to wear leg braces and attending physiotherapy check-ins up to the age of eleven to help me with my gait and balance. Due to the way that I walked, my feet began to turn outwards until I developed bunions that further hinder my ability to walk comfortably, resulting in a slight limp that gradually gets worse if I walk continuously for too long.

Despite this, growing up, I was never really given the opportunity to learn about my own disability, and was often discouraged from referring to myself as a disabled person because I am not outwardly perceived as one. Because I am very self-conscious about the way my feet look, I almost always wear socks and shoes when I am out in public, hiding the only perceptible difference associated with my body. Thus, most people are unaware of the effects that my disability has had on me unless I tell them. I have also been consistently told that I should work on correcting my limp, as opposed to embracing myself, and avoid labelling myself as a disabled person. Because of the mild nature of my disability, I constantly felt, and still feel, as though I am not qualified to speak about it, and I often see myself as ‘not disabled enough’ to be described as such. Even though my disability affects me every single day, I have been taught to push it down and pretend that it does not exist.

After returning home from Toronto, I made a vow to myself that I was going to do something, anything, to bring awareness to the fact that even in a place like Union Station, the hub of travel in a big city, people with disabilities are not given the help that they need to thrive. Despite the rage that I felt towards the injustices of the world, I remained silent about it because I did not feel that it was my place to speak about it. Meeting Amanda Leduc at the Eden Mills Writers’ Festival in 2018 validated my own voice and helped me embrace my cerebral palsy—making me realize that I do have a place in the community. As many people are already aware, Amanda has done amazing work both in literature and involvement with the disabled community, and is someone who faces similar challenges I do with cerebral palsy. For the first time, I felt entirely seen and understood, and I will channel Amanda’s words and impact for the rest of my life. She has inspired me to begin delving into research on disability representation in literature, and use my love of books to make positive and effective changes, even if they are small.

Self-isolating in the time of COVID-19 has given me the opportunity to reflect on how my own disabled body works, and for the first time in my life I am learning about myself in ways in which I was never encouraged to do before. It is also important to note that isolation is something that has been affecting disabled people for so many years before this pandemic began; it is not ‘new’ for them, it is just their life. COVID-19 has given me a glimpse into what this isolation feels like, and pushed me to advocate for the rights of my friend in particular in times when her family can’t be there for her. It is crucial to put in the effort to care for someone who is disabled – to make sure that they continue to have positive experiences that enrich their life, and consistently check in on them to lessen their feelings of isolation. Disability should not prevent someone from having the same basic human life as able-bodied people; they just might navigate that life a bit differently.

Reading books on disability activism and representation, particularly by queer writers and/or writers of colour, has helped me learn about the intersections of spaces I have only begun to insert myself into. I’m slowly making my way through an ever-growing library in my room. The two books that I am currently reading are Amanda Leduc’s Disfigured: On Fairy Tales, Disability, and Making Space, and Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice, the latter of which has emphasized the importance of building a community of disabled individuals that can come together and support one another despite a collective sense of isolation. Through processing books about disability, whether theoretical or the theory of our lives performed in fiction, I am learning how to advocate for myself and others around me and dispel the isolation that comes with being disabled.

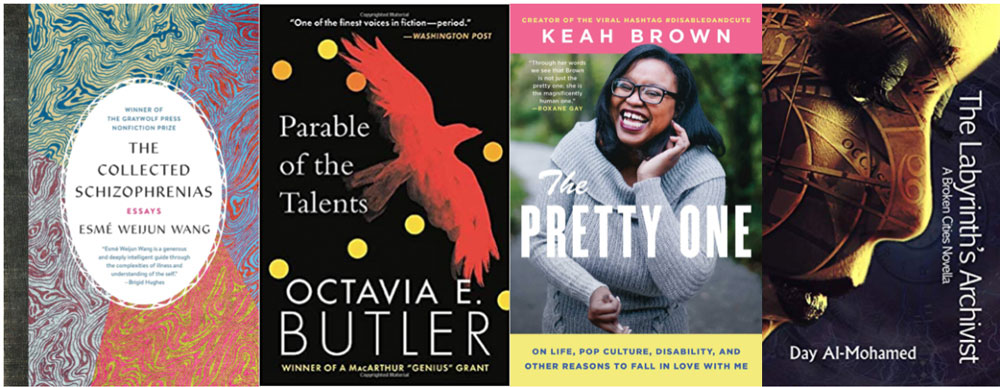

Below are more books – fiction and nonfiction – that I’ve been wanting to read to continue exploring the world of disability studies:

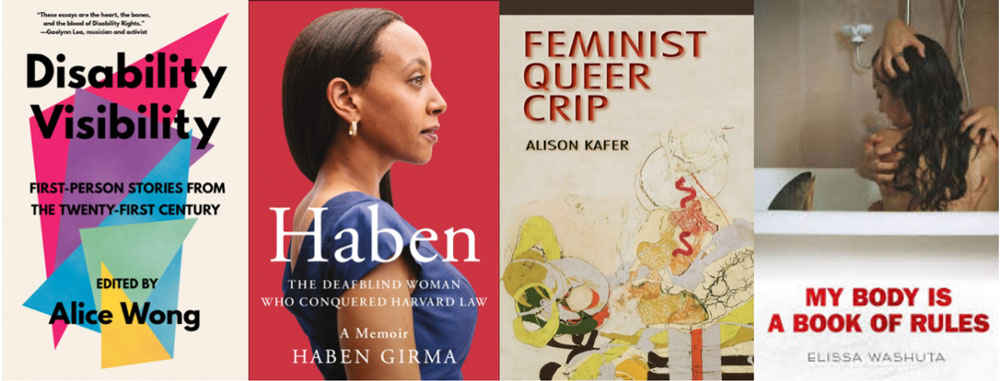

Disability Visibility: First Person Stories from the 21st Century, edited by Alice Wong

This collection brings together the voices of many contemporary disability activists, giving readers a glimpse into the world through which disabled people must navigate. It highlights the complexities of everyday life as well as the overwhelming passion that activists have within this community.

The Labyrinth’s Archivist, by Day Al-Mohamed

The Labyrinth’s Archivist is a science-fiction novella that focuses on a gifted mapmaker (archivist) who has the ability to recall every trick, story and detail from several other worlds. She cannot, however, participate in the “fabled” mapmaking process of the Archivists because she is blind.

Haben: The Deafblind Woman Who Conquered Harvard Law, by Haben Girma

Haben Girma’s memoir redefines disability as “an opportunity for innovation.” Her humorous and breathtaking story takes readers through her childhood during the Eritrean War to her life in America. After graduating from Harvard Law, she now works as an advocate for disabled people.

Feminist, Queer, Crip, by Alison Kafer

Alison Kafer reimagines a future for disabled people that does not include pre-determined limits and challenges the notion of able-bodiedness as the norm. By juxtaposing other movements together with disability justice, Kafer envisions a new, more inclusive world for feminist/queer/crip alliances.

Parable of the Sower and Parable of the Talents, by Octavia E. Butler

Parable of the Sower and Parable of the Talents is a science fiction duology that focuses on a young woman named Lauren Oya Olamina, who possesses what Butler calls ‘hyperempathy’ or ‘sharing’ – the ability to experience others’ pain.

The Pretty One: On Life, Pop Culture, Disability, and Other Reasons to Fall in Love With Me, by Keah Brown

A collection of thought-provoking essays by Keah Brown, creator of the #DisabledAndCute viral social media campaign. Through her writing, Brown explores what it means to be Black and disabled within a white, able-bodied world.

The Collected Schizophrenias, by Esme Weijun Wang

Wang delves into the stigmatization around complex mental and chronic illnesses. She opens with her own journey to being diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder, and continues into essays on navigating broader topics like fashion and higher education while dealing with mental illness. Wang’s background as a former lab researcher at Stanford allows her to effectively balance both research and personal narrative in this very intimate collection.

My Body is a Book of Rules, by Elissa Washuta

Through a series of essays set in her 20s, Washuta intertwines her experiences with manic depression, sexual trauma, and ethnic identity, creating a captivating collection that juxtaposes the humour of pop culture with intimately personal memories.