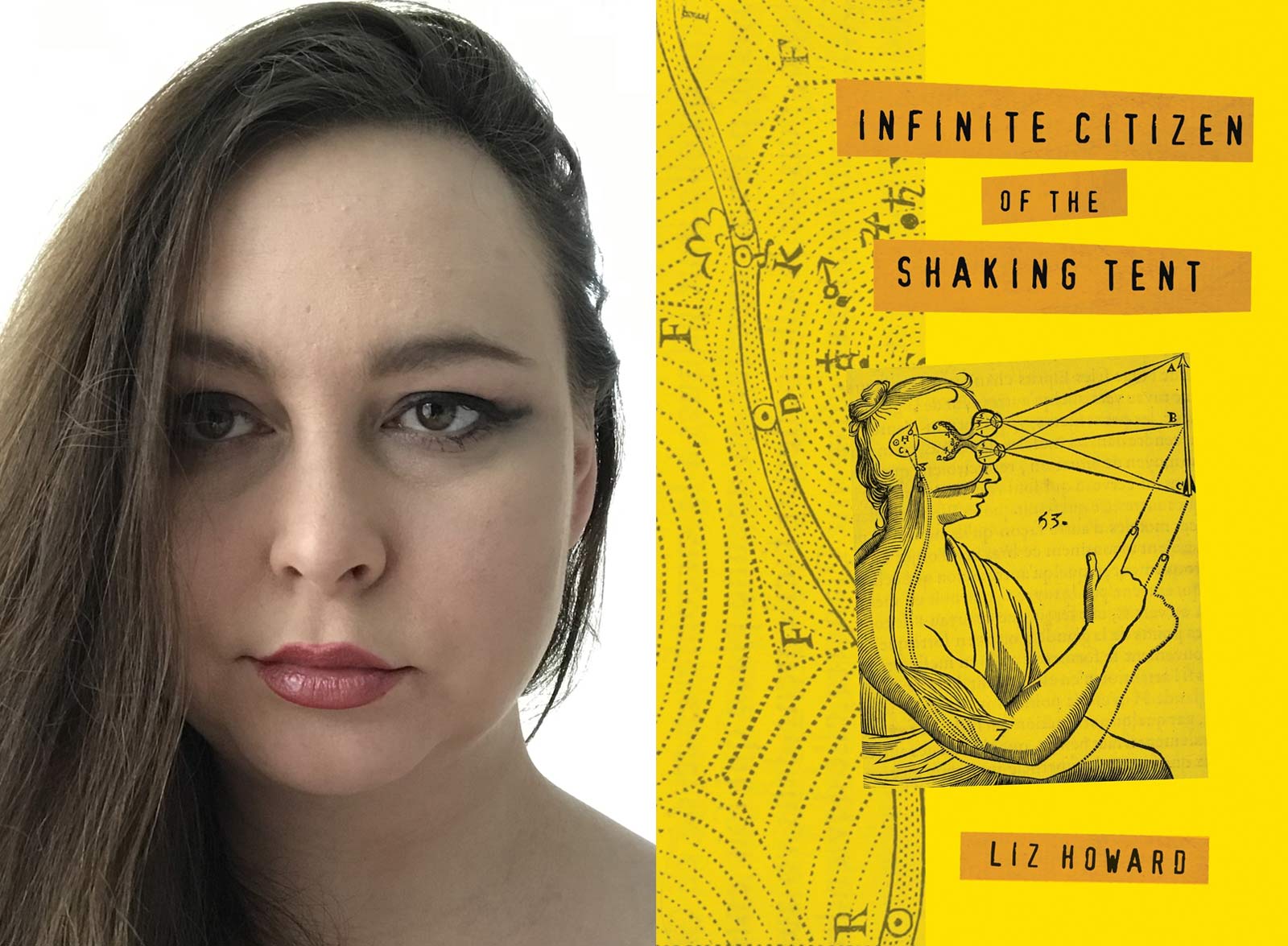

In the following interview, Manahil Bandukwala chats with poet and fellow festival author, Liz Howard, whose debut poetry collection, Infinite Citizen of the Shaking Tent won the Griffin Poetry Prize in 2016. The author spoke about contamination and poisoning in northern Ontario, developing an ecological consciousness, and being a citizen beyond citizenship.

To celebrate the upcoming Growing Room Festival 2020, we are chatting with a few festival authors to learn more about them and their work until the festival rolls around. You can read all the #GrowingRoom2020 interviews here. In the following interview, Manahil Bandukwala chats with poet and fellow festival author, Liz Howard.

Liz Howard’s debut poetry collection, Infinite Citizen of the Shaking Tent (Penguin Random House, 2015) won the Griffin Poetry Prize in 2016. She is of mixed settler and Anishinaabe heritage. In this interview, Manahil Bandukwala talks to Howard ahead of her appearance at Growing Room 2020. Read what Howard has to say about contamination and poisoning in northern Ontario, developing an ecological consciousness, and being a citizen beyond citizenship.

ROOM: Hi Liz, I’m excited to talk to you about your work and your upcoming appearance at Growing Room in 2020! In your poem, “Contact,” you write, “the sweet radiation of the earliest flower,” how toxicity seeps into the land. Why is this theme so prominent in Infinite Citizen of the Shaking Tent?

Liz Howard: The line you quoted comes from a poem in a suite that seeks to “re-write” Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s epic, “The Song of Hiawatha.” His poem was a racist and inaccurate account of Anishinaabe oral history from the southern Great Lakes region. In the suite of poems, under the section of my book titled “OF HEREAFTER SONG,” I sought to write through Longfellow’s verse, inserting language harvested from reports on the sociological and environmental consequences of the colonization and industrial development of the Great Lakes region. That being also the region where my own Anishinaabe family came from before moving further into northern Ontario. Contamination and toxicity are referenced throughout the book because they are a part of all human and non-human bodily processes and histories now. And the impact is greater, contaminants are at higher concentrations in some communities than others. While I was writing this book, the poisonings of communities like Grassy Narrows, who are still living with the devastating consequences of mercury contamination, and the Aamjiwnaag First Nation, who have been subjected to the greatest exposure of effluents/contaminants from Canada’s “chemical valley” such that this exposure has had a measurable effect on birth rates, was very much on my mind. Growing up in my hometown there were a few instances where we were made aware of environmental contamination from industry. One was an alert that a tanker filled with a poisonous chemical had derailed on the railroad. The other was that a poisonous chemical from treating lumber had leached into the town river where the town drew its water supply. For days people in town were advised not to use or even bathe in the water from their faucets. I remember reading the town paper about advisories for herbicidal spraying of regions clear-cut by forestry corporations. Those would often be the best places to harvest blueberries, which I often did with my mother and grandmother. Growing up with the awareness that these poisons were in the food, water, air and otherwise clearly had a significant impact on me. It led to me developing a wider ecological consciousness which would become thematic in my writing.

ROOM: I’ve been studying 20th and 21st century poetry and it’s interesting to see the crises and anxieties poetry movements write back to. In our current world, I see a lot of poetry of the climate crisis. How does this come into your own writing—for example, Infinite Citizen of the Shaking Tent really interrogates this.

LH: Infinite Citizen opens with a poem that references the terraforming of Mars as a possible project toward the retreat from a world inhabitable due to the effects of capitalism, a capitalism that has led us into the ever-evolving climate crisis we are in. I remember listening to a lecture years ago where the speaker said something to the effect of that it was ideologically curious or consistent that for some it is easier to imagine creating a whole viable atmosphere and ecosystem on a distant planet rather than ending exploitative capitalism, or just capitalism full stop. I don’t know how you write now without climate concerns influencing your writing.

ROOM: I love the lines, “just below this earthen burial urn is our / mammalian warmth place a hand / to tend it” from your poem, “Anarchaeology of Lichen.” There’s a beautiful blur between life and death. How do you approach the relationship between the two?

LH: That quote is, in part, a reference to Thomas Browne’s “Hydriotaphia, Urn Burial, or, a Discourse of the Sepulchral Urns lately found in Norfolk,” something I was reading at the time I was writing that piece. I have always been fascinated by death as an inevitable part of the life process. I lost my grandfather when I was four years old. In the French-Irish Canadian tradition my mother and I were raised in there is a wake before burial of a person who has passed. My grandfather had in many ways acted as a father to me as my birth father had left due to substance and related issues. I saw my grandfather’s body at the wake and kissed his cheek, watched as his coffin was lowered into his grave. Years later, we moved in with a man my mother later married who lived across a dirt road from the cemetery. When they married, and my youngest brother was born, I had to move into the unfinished basement. It became clear to me that I was sleeping at about the same level underground as the people in the cemetery had been buried. I dreamt of them often. In a way I came to understand life and death as a continuum. I’ve always found something compelling by considering the fact of death within poetry, poetry being ultimately a celebration of life, continuance. I don’t know what to say more than that. I experienced loss very early and came of age sleeping maybe ten feet away from interred remains. I suppose this is my poet origin story?

ROOM: How does your background in science come into your poetic practice?

LH: My background in science comes into my work in a way that I think someone who studied literature would have that come into their work. It’s my foundation in some ways, my pool of linguistic reference. A region of specific inquiry whose theories helped to inform and organize my understanding of the world after I lost faith in the Catholic worldview I was raised in. Indigenous science is increasingly being recognized and written about. As a lifelong learner I am committed to a continual practice of “two-eyed seeing” in which traditional knowledge is considered alongside findings from Western science.

ROOM: In an interview in carte blanche, you say, “I began to wonder if I could use poetic practice as a kind of Shaking Tent, a vehicle of inquiry within my generative, if contaminated, mind-body.” I loved that line—can you talk more about the relationships between identities, selves, and citizenships?

LH: I could probably talk about those relationships in multiple books. Likely I will. This is hard! You’re asking me some significant questions and I’m honoured and humbled by what you are offering me to respond to. The space to speak of these facts, concepts, personal territories that are and will probably remain very raw for me, even as I write through them, and somewhat publicly at that.

When I was about seven years old my mother sat me down with an information pamphlet from one of the reserves near town. She told me I was native because my birth father was. I’d never met him; he was the greatest ghost of my life—this missing person who made me “different.” I was told a lot of confusing things about being native and being the child of my birth father. Suffice to say growing up like this caused me to feel as though I had multiple selves within me. Who I felt I was, who I felt I should be (informed by Catholicism and Catholic school), and who I could possibly be (if I had access to family and culture I was estranged from). Citizenship? What does that even mean, for someone in my predicament, I always thought. What does it mean to be who I am with what I do know? In learning of traditional practices, I came to write that I wanted to be a “citizen in a shaking tent.” To be a citizen of something beyond citizenship. Part of something that has always been. Something that I have always felt.

ROOM: I see a lot of conversation happening about whether to translate language and culture, or whether to let readers do the work in finding out. I find myself wavering between the two sides and am curious to hear your take on this.

LH: I’ve used Anishinaabemowin in my book and will continue to do so in the future. I see nothing wrong with having a glossary at the back of a text. I’ve gotten the most flack for not providing explanations for scientific and otherwise academic terms in my writing. I personally always appreciate any opportunity for learning. If I read a text that intrigues me, and just say it is not all in a language I can read, I will look things up in order to fully understand.

ROOM: You’re the poetry mentor for the Writers’ Trust’s new mentorship program. I’ve found that as a young writer, mentorship is so invaluable in crafting and shaping my work. What does a mentor-mentee relationship look like to you?

LH: When I work with another person, a student, a peer, I always consider what they share with me on its own terms. Meaning I don’t impose (as much as I can consciously) my own aesthetic biases in my advice. I try to assist with the development of the writer’s vision for a piece as much as I can. I provide a lot of links to poems, readings, resources that I think would be beneficial. Aside for the exceptional experiences I’ve had in my MFA and a few workshops I’ve never had the kind of mentorship I’m now providing. I give it all my very best.

ROOM: Who are some poets whose work you’ve been excited about lately?

LH: Kaitlin Purcell, Cassandra Blanchard, Brandi Bird, and Ivanna Baranova.

ROOM: Thank you so much for this interview!

You can join Liz Howard at the following Growing Room Literary & Arts Festival events on March 14 and 15: