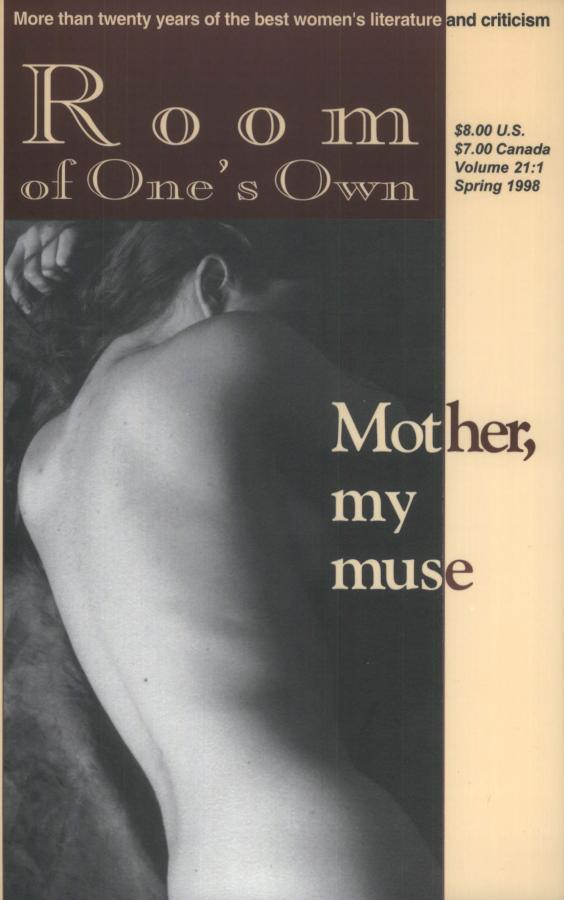

Mother, My Muse | 21.1

1998

Digital only; out of stock in print.

My mother made me tea in a pop bottle on the mornings I spent watching Mr. Dress Up. She introduced me to Anne of Green Gables and proofed my high-school English essays, often suggesting better words than the ones I chose. She wrote me long letters in perfect penmanship when I lived far away and still sends me newspaper clippings she thinks I’ll enjoy.

She’s an eclectic reader and watches her soap opera religiously. She’s a gambler and a night person, she bakes braided bread and I’ve never seen her cry.

In one way or another I can trace everything I am back to her. Which, as this issue demonstrates, is what many, if not all, of us can do. In the following pages it becomes clear that mother is at, or somewhere very near, the heart of all of us. And in our heads and in our pens.

There are a myriad of mothers here, both on the lines and in between them. Mother as muse, mother as protagonist— and antagonist. Mother as a source of inspiration or exasperation. There are reluctant moms and drowning ones, decrepit moms and forgetting ones. And the writers showcased in this issue portray mothers both plaintively and profoundly.

One thing is common: one body becomes two but there is always a connection. It’s not necessarily a happy thing as the confrontations between Sally McNall’s warring mother and daughter show. But it’s always intense. Jenny Charchun sings the strength of this bond in “Starting Sunflowers.” “Finger grip./ Of spring?/ My mother?/This is her season to draw me home… My body /is braced/ for the ‘happy birthday.’ / The day that pairs / my mother and I. / I imagine / seeds bursting. / The pain of birth. / Sunlight. / Tender leaves / opening / two by two.”

There’s tragedy too. Chris Wiesenthal’s essay bursts with the raw emotion of losing a mother too soon. She is haunted by dreams of her mother, buffeted by anger and anguish; yet, in the end, finds comfort in the love that was there.

There is motherhood and getting used to clean ing tiny chins and talking through streams of wails as Lenore Baeli Wang so eloquently explains in several poems.

These pages also hold the anguish of wanting to be a mother and not succeeding, as experienced by the barren women in Audrey Poetker-Thiessen’s poignant pieces, the desperate one in Charchun’s “Pushing Babies” and the grieving women in Julie Roorda’s sad story and Sharon Temple Lieberman’s “To Vincent Van Gogh, After A Miscarriage.”

We are given menopausal mothers by Susan McCaslin and sick and aging mothers by Reva Rasmussen and Olive Sullivan. There are a handful of fathers (in Margaret Gunning’s “Lightning”), grandmothers (in Heather MacLeod’s poetry) and aunts (Joyce Hinnefeld’s conflicted Alma) thrown in for good measure.

These mothers don’t always jump off the page and proclaim their influence in vibrant voices—some whisper in and out of the pieces, their impact like a gentle breath, soft with significance.

But there is a constant: there’s a mother in all of us. Our own mother. Ourself. Our best friend’s mom, our lover’s. And they provide a wealth of possibilities for writers and for readers.

So read on, my mother, my friend.

$10.00

Additional information

| Delivery | Canada, USA, International, Digital |

|---|

In this issue: Virginia Aulin, Ronnie R. Brown, Danielle Bugeaud, Jenny Charchun, Margaret, Gunning, Joyce Hinnefeld, Mary A. Landi, Sharon Temple Lieberman, Lesa Luders, Heather MacLeod, Susan McCaslin, Sally Allen McNall, Audrey Poetker-Thiessen, Reva Rasmussen, Julie Roorda, Olive L. Sullivan, Lenore Baeli Wang, Regina Weaver, Chris Wiesenthal