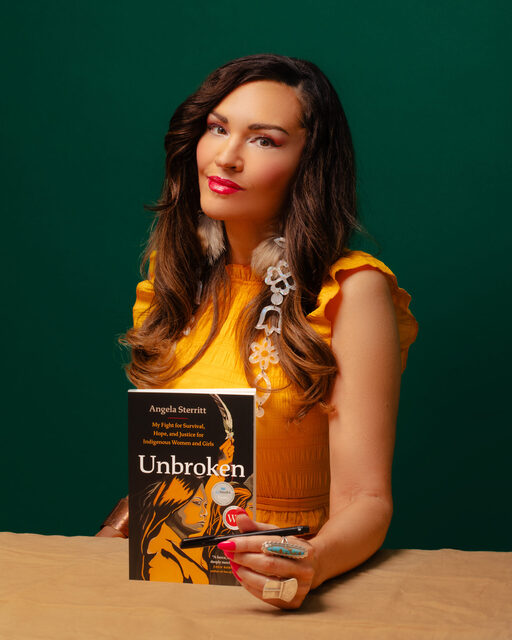

Photo credit: Georgie Lawson

Angela Sterritt is an award-winning investigative journalist and national bestselling author from the Wilp Wiik’aax of the Gitanmaax community within the Gitxsan Nation on her dad’s side and from Bell Island Newfoundland on her maternal side. She worked as a multi-platform journalist with the CBC for more than a decade, and hosted the award-winning CBC original podcast Land Back.

Her book Unbroken, about the murders and disappearances of Indigenous women and girls as well as her own fight for survival, was published by Greystone Books and became an instant national bestseller in May 2023. It was also a finalist for both the Governor General’s Literary Awards and the Hilary Weston Writers’ Trust Prize for Nonfiction. This year, Sterritt is the judge of Room’s Creative Non-Fiction Contest. She spoke with Amelia Eqbal about the journey she’s been on over the last year with Unbroken, what her experience was like leaving (and contemplating a return to) journalism, and what her nascent second book has already taught her about writing.

Note: This interview was conducted over Zoom: as such, Angela’s responses have been shortened for brevity.

—–

ROOM: First off, I want to congratulate you on Unbroken being shortlisted for this year’s Indigenous Voices Awards. What does that recognition mean to you?

ANGELA STERRITT: This is the fourth award I’ve been nominated for: I was also nominated for the Governor General’s, the Hilary Weston [Writer’s Trust Prize], and the Jim Deva [Prize for Writing That Provokes] was the most recent one, but being recognized by your own people, it holds so much weight in terms of your own people seeing you succeed, and knowing that your work is valuable for Indigenous people. I mean, I wrote the book in hopes of educating the non-Indigenous population. But I also wrote it for family members and survivors out there to feel seen and to feel empowered, and to kind of— whatever the opposite of gaslighting is, you know? To really show people that we acknowledge and understand colonial violence and the extreme harms that it did, but also that there’s a path forward in terms of healing…. So the award by an Indigenous group, it’s everything.

ROOM: I was thinking about that a little bit because the book’s been nominated by other organizations like the Writers’ Trust of Canada and the Governor General’s Literary Awards. I’m wondering how it feels for this particular book to be nominated or recognized by more Canadian, colonial organizations. Does that feel like progress to you?

AS: As Indigenous people, we are kind of like the opposite of white feminism where we’re not searching for individualistic power and prestige; it’s all about the collective and the integrity of keeping that in mind, and having humility to walk on behalf of so many different layers of identity. But to be acknowledged by a colonial institution, I mean, I remember for years Indigenous authors weren’t recognized at all. Like Lee Maracle, one of the most incredibly well-known and beloved authors in Canada, at one point had to go international in order to be seen as an author, period, in order to be acknowledged by [literary] peers. And so when I started seeing Indigenous people being recognized, it helps the stories that we tell be seen, empowered and listened to.

My book has been number one a bunch of times, but I just find that almost shocking because I didn’t anticipate this at all. I didn’t think it’d be a flop, but I thought it’ll be like one of those stories that you do where maybe it doesn’t have a million hits or a bunch of people aren’t reading it, but it’ll be on the public record for people to know.… But to have it being recognized by not just Indigenous people, but by the larger Canadian society that’s often silenced Indigenous voices and gaslit Indigenous people when we share our stories, it’s incredible because it helps empower other Indigenous authors coming up who want to have their stories heard and read.

ROOM: Absolutely. That kind of leads nicely into my next question about your experience with writing Unbroken. It’s this beautiful marriage of memoir and heavily researched reporting, as you mentioned, which is a very unique blend. I don’t know if I’ve really read anything else like it. And I know that in past interviews, you’ve talked a lot about how heavily you thought about that decision to include your own personal story as you also told the stories of these missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls. Before publication, were you ever worried about how the book’s form might be received, and in the year that’s passed since publication, have there been any surprises or interactions that have stuck with you regarding how the book’s been embraced?

AS: When I first thought of the idea of investigative journalism blended with memoir, I couldn’t find any examples out there at all…. No one had heard of this style, and so a lot of people were questioning that. I wasn’t sure. I think that was a big part of, is this just going to be a flop?

And then when it came out, people were very intrigued by it, and calling it “genre-bending.” One of the things my editor and my agent said is by including your story through this format, you’re giving people an anchor to take them through all these heavy, news-y topics, so it’s not such an academic read. And I think that was a brilliant suggestion that they offered, because it has been really well-received. It’s very interesting how different the reads are. I have a lot of Indigenous younger women being like, “I felt empowered by your book, I felt seen.” And a lot of older people, even Indigenous people being like, “This is really heavy. This was a really hard read.” People have called it a page-turner; I know people who’ve read it in two days. A lot of non-Indigenous people are like, “That was a very difficult read, but a very important read.” So it’s interesting how different the takes are on it.

ROOM: On that note, coming from your journalism background I’m sure you’re familiar with the age-old journalism principle of “remain as objective as possible” and to not “become” the story. And I’m sure you’ve heard that as young writers, we often hear the advice to “write what you know.” What has your experience writing Unbroken taught you about how to approach topics or subjects that are personal to you, where others might perceive bias, when it comes to writing creative nonfiction?

AS: I mean, without my experience in this book, it wouldn’t have reached the level that it has for sure. I know that for a fact, because I have authority on this topic. So it’s interesting that we hear that in certain formats…. But in thinking about podcasts, the most powerful ones are the ones where people say, “I’m the one who’s telling this story because I’ve lived this,” you know?

ROOM: Connie Walker is maybe a great example.

AS: Connie Walker, yeah, saying, “My dad attended residential school,” you know? But when it comes to news, it’s like you can’t ever tell your audience you really know what you’re talking about. It’s a bit strange that there’s this very old guard when it comes to news. But when it comes to more modern forms of journalism, it seems important to let people know that the person telling the story has valuable insights.

When I’m reading a story by an Indigenous author, from a certain perspective, I feel like there’s a level of trust that we’re looking for, right? When we’re consuming the news we want to feel like we trust the person telling the story. And so it’s odd that for most of my career, I was not trusted to tell the truth when it came to Indigenous people, even Inuit people thousands of kilometers away from my community, because there’s somehow a bias wrapped up in being Indigenous. And I think that is really wrapped up in the colonial bias of news … so there’s a colonial slant that we need to constantly be fighting against. It’s been an interesting journey being out of journalism, and now thinking about going back into it. I had to cleanse myself.

ROOM: Oh, interesting. You’re thinking about jumping in again?

AS: I was extremely burnt out. And so now I’m like, okay, I can do this. But I needed to cleanse myself of the toxicity of it or the biases of it, and jump back in being like, this is okay, to tell a story from my own perspective…. It’s really hard when you’re confronted with racism every single day. That’s what burns people out, is racism from being met with hostility in your pitches or just you as a person can’t be who you are and you’re forced to assimilate.

ROOM: In your TEDx talk, you talk about how writing was one of the most powerful tools you had available to you as a young person experiencing homelessness, when it came to survival and figuring out who you wanted to be while fighting against colonial systems of oppression every day. How has your relationship with writing changed or stayed the same since your earliest days as a writer?

AS: In my keynotes, I talk about how my pen started as a counselor, and then became a light to pave the way forward for Indigenous people to tell their stories, and then it became an agent of change when there was pushback against the type of stories that I wanted to tell. I’m writing my second book now — and news will come out about that soon — but it’s very healing. Writing Unbroken was incredibly healing, and not just the writing; it’s also the releasing of the book, and having a hundred people standing in line to sign the book and coming up to you and thinking they know you, and crying; you kind of need to hold space for people.… And so it’s been very healing. The pen is healing, still, in that way.

The second book I’m doing is really about healing other people and changing perspectives on something that can be very dark, and looking at things in a very unique way. And so as much as my pen had to become an agent of change for many years to fight to tell the truth, from my perspective, I don’t feel like I need to do that anymore. I feel like I’m sitting in a place where my main purpose in life is to focus on healing with other Indigenous people, to empower us so that we can focus on reclaiming our languages, our cultures, our institutions, our laws. That’s incredibly healing for me, to think about how powerful and how much leadership we have to offer the rest of the world. I just don’t feel like I need to be fighting anymore, because it’s draining, right?

ROOM: Absolutely. It’s not funny you say that, but it’s interesting that we’re on the same wavelength, because my next question is that, you ended your TEDx talk in 2020 with a vow that you’d “keep on fighting your good fight in media,” and keep on telling those stories and changing that one narrative when it comes to Indigenous representation. So maybe to put a finer point on what we just started talking about, what does that mission look like for you now?

AS: That’s a hard one, because I feel like there’s a lot of people who have come to me after I left my job and have apologized for the way they treated me or for what they witnessed. I was treated really, really poorly, and I just was constantly fighting for my place at the table and to have Indigenous stories be accepted… and I feel like I don’t have to do that anymore in the author world. My truth is valued.

And so when I’m giving my keynotes now, I’m not fighting. I’m empowering people to have curiosity, to have compassion and to have courage. People love it and they value it, and they value me. I feel like now that I’ve left journalism, I’ve been safe enough to build up who I am as an Indigenous woman, who I am as an investigative journalist, who I am as a mother, who I am as a community member. And that’s what we all deserve: a space to dream, to believe in our gifts. And so, that’s an interesting question because I don’t feel like I’m fighting anymore. I’m building a collective wisdom and a collective strength.

ROOM: You’re the judge for Room’s Creative Non-Fiction Contest this year. What’s a piece of creative nonfiction that made you fall in love with the genre?

AS: When I first started writing the book, I didn’t know how to even write a book. Waubgeshig Rice really said, “If you want to be a good writer, you need to read how you want to write.” And so I really used Tanya Talaga’s Seven Fallen Feathers as kind of a guide, because I just thought she’s brilliant. I love her writing. It’s very creative, it’s very beautiful and also is laden with hard truths and important lessons for us all to learn about. And Alicia Elliott, I think, is an incredible writer. Her book, A Mind Spread Out on the Ground, also brilliant. Jessie Thistle’s book [From the Ashes] is beautiful. What an incredible writer. It’s so well done. So those are the three books that I sort of fell in love with.

ROOM: Excellent choices. And as the judge of this year’s contest, what is your advice for anyone who’s looking to submit?

AS: Don’t be afraid to decolonize your writing. Don’t be afraid to write in your language and not translate it. Don’t be afraid to do something completely different. But also really read how you want to write, that’s really important…. Read, read, read as much as you can. Don’t be afraid to be completely outside the box, and be yourself, and not assimilate yourself. And don’t dilute the truth.