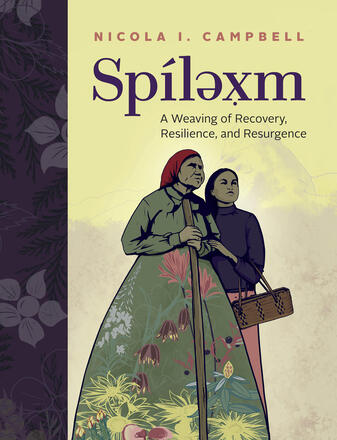

Nicola I. Campbell is a Nłeʔkepmx, Syilx, and Métis author and educator known for her award-winning children’s books, Shi-shi-etko and Shin-chi’s Canoe, both of which have been made into short films. As of last year, she published both Stand Like a Cedar and Spíləx̣m: A Weaving of Recovery, Resilience, and Resurgence, the latter of which is a memoir discussing her experiences as an intergenerational survivor of Indian Residential School, the Indigenous relationship to the land in the place now known as British Columbia, and the process of moving through grief.

Nicola I. Campbell is a Nłeʔkepmx, Syilx, and Métis author and educator known for her award-winning children’s books, Shi-shi-etko and Shin-chi’s Canoe, both of which have been made into short films. As of last year, she published both Stand Like a Cedar and Spíləx̣m: A Weaving of Recovery, Resilience, and Resurgence, the latter of which is a memoir discussing her experiences as an intergenerational survivor of Indian Residential School, the Indigenous relationship to the land in the place now known as British Columbia, and the process of moving through grief.

After being floored by the multi-disciplinary approach of Spíləx̣m (ShpEE-luh-khm, the last syllable spoken with the back of the tongue slightly raised), we were immensely grateful when she accepted the invitation to be the commissioned writer for the 45.4 issue of Room. Here, Campbell met with us via Zoom to discuss writing Spíləx̣m, the impacts of colonialism on her and her community, and the importance of embedding Indigenous histories and stories into education.

Micah Killjoy: What made you decide on the title for Spíləx̣m?

Nicola I. Campbell: I wanted a word in my language that reflected what was inside the book—it’s a collection of stories and events that had taken place in my memory, since childhood, as well as memories spoken by my elders throughout my life. With that in mind, I chose to use the word ‘Spíləx̣m’, which translates to ‘remembered stories, moccasin telegraph, or news’.

MK: What made you decide to write a memoir?

NIC: This was actually my master’s thesis. When I started my master’s degree, I was going to write a novel. Keith Mallard was my thesis advisor at UBC. I already had a collection of poetry and non-fiction prose that I had written. I was trying to plug away at that novel when my aunt, out of the blue, gave me a stack of letters and said, ‘Your mom sent those to me when your dad was still alive.’

I reread them a few times and arranged them chronologically. That was when I wrote the poem “July 26th, 1973”, which is about the day my dad passed away. The last letter to my aunt was at the start of July of that year. My dad passed away after having saved two children from drowning at the Batoche Days celebration, July 26th. I wrote what I had been told about that day.

Then I reflected on how my mom returned home to the Nicola Valley. It was a natural process from there. “sptétkʷ” is about how the land called her home because our homelands are woven into her being.

Through my graduate studies, I periodically had student-thesis advisor conversations. I told Keith about the letters and that I had printed hard copies of all my work and that I had organized it chronologically. He said, ‘Bring it to our next meeting, I’d like to take a look at it.’ I brought him this big stack of pages, alot of which I had written during my BFA and MFA course work. He flipped through and said ‘Nicola, why are you writing a novel? This is your thesis right here’. [laughs] I was pretty shocked.

Through the years since graduating, I put it away, returned to it, put it away. I submitted to quite a few publishers, and was turned down several times due to its multidisciplinary nature… [laughs]

MK: That’s the experience.

NIC: Because of the multidisciplinary nature, right?

One publisher agreed to publish it with the understanding it would be split into two separate manuscripts. After I signed a contract, however, I realized that this work just did not function the way it needed to as two separate publications. This was one thing Keith Mallard had said: ‘Publishers, especially in the English literary community, do not like to publish multi-disciplinary works, especially because this is a memoir. They will ask you to separate this into two disciplines. I want you to say ‘no’. You have to keep this together.’

It’s weird how a manuscript will sit on you. I would put it away and think ‘no, it’s too personal’ and then it would start bothering me again, and I would return to it. I am grateful to a few editors who took the time to read it and provide genuine feedback. In 2017, I met Garry Thomas Morse through the Indigenous Editors Circle at Humber, as a fellow Indigenous writer. Garry later contacted me on behalf of Highwater Press, to see if I had any works in progress. They reviewed it and agreed to keep it together as one work. Last in the process, Garry requested in Winter 2021 that I write a final closing piece in the present voice.

MK: Getting a manuscript published is such a process.

NIC: I did not have the intention of writing a memoir, it just kind of came together.

During my Comprehensive Exams for my PhD I read a lot of traditional and contemporary creative and critical stories and published work by Indigenous writers. Leanne Betasamosake Simpson and Neil McLeod are two of those writers (Dancing on Our Turtles Back, Cree Narrative Memory, Indigenous Poetics in Canada), as well as having Dr. Jeannette Armstrong and the late Dr. Greg Younging on my supervisory committee at UBC Okanagan. This stage of my studies had a huge impact on my thought process. It helped me to reflect on my voice and question the ways I could go deeper into my Indigeneity, in an effort to connect to who I am as Nłeʔkepmx, Syilx, and Métis writer. I grew up within the maternal side of my family and community, in Nłeʔkepmx and Syilx traditional territory—as Interior Salish. Scwexmxuymx is the land where I grew to understand myself as a human being, as an Indigenous woman, as Nłeʔkepmx and Syilx. I wanted to create work that is deeply connected to the teachings of my ancestral grandmothers and grandfathers as a way, to show a trail for other Indigenous audiences who were also struggling.

When I decided to go forward with publishing Spíləx̣m, one of the things I reflected on was healing and grief. I thought about other Indigenous people who might be struggling with intergenerational trauma and trying to understand what has taken place here in “British Columbia” since colonization.

I realized that a lot of us have considered suicide and giving up because the intergenerational hurt is tremendous. As Indigenous people, our interconnectedness spans generations. Our families are huge—often number in the thousands. As a result, we are deeply interconnected from one community to the next.

And because of that, our love is immense. Many families still struggle because there’s so much unresolved as a result of colonization. Reconnecting to our cultural teachings and our cultural practices, but also really reflecting and understanding the ways it has impacted our ancestors. They never gave up. When the children were taken, when the pandemics came through and killed entire villages, our ancestors never gave up. If they had given up, where would we be today?

I realized I have an obligation to my Elders and to my ancestors to really work hard to carry on and share that love and share those teachings. To try to continue empowering our younger generations so that they will find the courage within themselves to do the work that needs to be done.

MK: As an assistant professor at the University of Fraser Valley what are ways you see that happening, or not happening, in education?

NIC: I was talking about that with my students. Most of the students in my classes are age 20 and under, Indigenous and non-Indigenous. I told them, ‘When I was 20, I never really thought of myself or the work that I do as significant, or that I would ever contribute to creating awareness or positive change in my own community or beyond, internationally. But then I published Shi-shi-etko and Shin-chi’s Canoe, and one of the things I realized was the power of stories and the power of our work in storytelling practice as Indigenous people.’

In Spíləx̣m, I wrote about an Elder I heard speak at a language conference in Seattle, where he talked about the power of stories to heal and transform. Last year, Christie Belcourt posted a really powerful statement about the power of stories. The late Dr. Jo-Ann Episkenew also wrote about the power of stories in her book. So many Indigenous writers and storytellers, share this teaching that we have to be conscious of our words, because stories are alive. Some say they are spirits and when they enter into us, we have to really be conscious about how we share them. Because once stories are released, they go out into the world and they do their work.

When Shi-shi-etko was published, I received a bad review from an Indigenous reviewer out east who said that it shouldn’t be classified as a “book about Indian Residential School” because you never see a residential school in the story. Shi-shi-etko was never supposed to be about residential school. It has always been about remembering who we were before Indian residential schools. The review was important because it inspired me to contact my publisher and say, ‘I want to write a sequel.’

I did not truly understand though, how once the stories were published, they would take on a life of their own. When I wrote Shin-chi’s Canoe, I made the decision to not talk about the details surrounding the violence and trauma of what took place at Indian Residential Schools. I wanted to reflect on the places and ways they survived. When the films were made there were people in the audience asking, ‘Why didn’t you show them crying? Why didn’t you show the devastation?’ I remember our Elders saying that they did not want to give the Indian agent the satisfaction of seeing them cry. The despair of our ancestors and family is not for audience entertainment.

I struggled with writing Shin-chi’s Canoe, because it was my first time sitting down with intention of writing a children’s book. I was also actively grieving what took place for my grandfathers and mother’s generations and worried about how my words would impact them. Children’s picture books are, somewhat like poetry, you have to be precise, strategic and spare with your words. You don’t have a lot of space. I knew other Indigenous voices would work together to fill those spaces. For the different age groups and audiences, they would come together and share the truths of the violence and suffering that occurred.

I am so grateful now, to see the work that has come out across Canada since they were published. And yet, there are still so many students walking into my classroom and they still don’t have a clue what took place.

MK: It’s disappointing, especially with all the coverage given to how much Canada supposedly talks about Reconciliation. Can you speak more to the lack of impact of Reconciliation in the classroom?

NIC: Growing up, we didn’t learn the nations or cultures of the Indigenous people in British Columbia. When I was in elementary school, I didn’t know I was Nłeʔkepmx and Syilx. When I moved in with my grand auntie, that was when I really started to understand my identity, and the importance of our language. All through high school we never learn a single thing about our neighboring nations, about Indigenous languages in British Columbia. When I started to work towards publishing Spíləx̣m I said, ‘Okay, if I’m writing something that’s going into the classroom then what do I want the teachers to think about? What conversations do I want the students to have?’ And one of those things was having educators reading, hearing and speaking about the truth of the genocide that took place in Canada, as well as why healing is so important.

That was also why I decided to list as many of our nations and our languages in British Columbia as I could in the poem “tmíxʷ. temexw. temxulaxʷ.” I know that there’s errors in that poem, but I thought, ‘I want to convey how vast and dynamic our cultures are.’ We’re here and we’ve always been here. Nations of Indigenous people have always had vibrant, dynamic, and powerful cultural ways of being and living on the land that has existed for thousands of years. And we never learn about this in the classroom because a lot of teachers are afraid. So, even if I get it wrong, I’m going to say them because I want those students to have them in their minds and hearts.

I read a blog by a parent whose child had picked up Shin-chi’s Canoe and brought it home from school. The parent wrote about how she would have never chosen the book for her child, but because her child brought it home, she was forced to learn and explore her own understanding while reading it with her daughter. She had to convey an understanding of why Indigenous children were taken from their parents and forced to live at Indian Residential Schools.

That blog was one of the ones that made me realize the true power that stories have to create understanding, to open hearts, minds and spirits in distant places across the country. It made me realize the sacred obligation we have as storytellers, and that we have the ability to inspire change through the hearts and minds of our children and, by extension, parents and teachers.

MK: Without a doubt. It’s vital.

NIC: Our DNA is right in this earth because our ancestors have been here for generations and generations. I remember my good friend talking about how everywhere we go, we’re walking on their footsteps. [Emphasis Room’s] When we’re traveling on our traditional pathways and harvesting our traditional foods—which we still do today—our villages and our communities still live according to those traditional harvesting practices.

It’s 2022. British Columbia, Canada, and Fisheries and Oceans Canada want to have control preventing us from harvesting. When we can’t harvest, our people are in a state of poverty due to lack of food. For them it’s all about business ventures and money, but as Indigenous people, those traditional foods are our life. We fish, we live off the land. That was something I wanted to write about because audiences need to understand.

MK: Final question: You talk often in the book and other interviews about canoeing and I get the impression it’s been an important activity for you. What are ways it’s impacted your life?

NIC: I learned to paddle when I first moved to Stó:lō temexw [traditional territory of the People of the River]. We didn’t have canoe racing in the Nicola Valley. I think that did a lot to make me a stronger person. I had a lot of respect for the way our coaches mentored us through traditional teachings.

A lot of it was about having a strong mind and self-discipline. It was sport, but it also impacted the way we live, culturally, and the way we cope with the hardships we’re faced with. It helps us to remain connected to our ancestral teachings.

Paddling taught me to have mental and physical strength and endurance as part of a team. But I also learned how important it is to be committed to my wellbeing—physically, emotionally, mentally, and spiritually. Fitness, as well as healing, is about commitment and self-discipline. It does not have to be geared towards a team. It is also about self-care. In that process, understanding that through our healing we are continually uplifting everyone around us.