Welcome to our first interview feature for Black History Month with Indigenous Brilliance!

In response to a lack of accessible education around the history of Hogan’s Alley and Black history in so-called “Vancouver,” Lexi Mellish-Mingo and Karmella Cen Benedito De Barros decided to embark on a short film project titled Where We Meet. We were lucky to get accepted as commissioned artists for the project and were able to move forward with creating a movement-centred, mixed-medium film piece. The following is an interview between Karmella and Lexi discussing the process of filming, the message behind our film, our hopes for Black community in Vancouver, and much more! We hope you enjoy and tune in on February 28, 2021 for a live online screening of Where We Meet! Keep up with us on the @indigenousbrilliance instagram and Facebook page for registration.

Where We Meet is an award-winning experimental film funded through F-O-R-M Festival 2020. The story explores the Black femme body and its relationship to space through conscious movement on the unceded and unsurrendered territories of the Tsleil-Waututh, Squamish, and Musqueam peoples, and follows our protagonist as they navigate isolation and seek a sense of belonging in a conflicting and new environment. Drawing on themes of double-consciousness and experimental embodiment, this story explores the relationship between Blackness and the environment in which this concept exists. Community dialogue is incorporated to address the filmmakers own subjective relationship to public space as mixed race Black-identifying people, and this film intends to hold space for diverse experiences of Blackness in so-called “Vancouver.” In times where racial politics exist in every crevice of society, the filmmakers escape temporal confines by decolonizing our situated experience, delving into the untold past, dreamy memories, and future imaginings.

Filmmaker Karmella Benedito De Barros // Filmmaker and Mover Lexi Mellish-Mingo // Music Composer Isaia Dobbs // Mover Janessa St. Pierre // Mover and Interviewee Kafiya Mudey // Interviewees Felix-Marie Badeau, Chelene Knight, and Rubie Smith Díaz.

Through celebrating movement in an intimately public manner, Where We Meet explores the intersections of Blackness, expression, community, isolation, anti-Black racism, colonial histories, and liberation on stolen land. This Afro-Futurist experimental-movement film follows the bodies and words of “Vancouver” based Black folks, and where we meet.

With this film, we explore movement as a conduit for decolonial communication. These movements navigate the constructs of Blackness, visually imposing depictions and questions of objectification, exotification, stereotypes, and anti-Blackness in relation to space. The relationship between the camera and the Black body becomes a window into double-consciousness, inviting the viewer to step into an alternate reality of embodiment and spatial consciousness.

As a visible minority, conscious of the intersections of our own existence, we may sometimes practice a form of shape-shifting for our own self protection, preservation, and out of fear. Du Bois’ concept of double-consciousness was key in the unbounding and expanding of awareness honed by Black people. As Black folks challenge sociopolitical power dynamics and media representations, the infrastructures of anti-Blackness and the white sterility of public spaces becomes exposed.

There is magic in knowing your truth and speaking it. To express one’s own blackness in a space white in ether and inhabitants has historically existed as a form of entertainment and othering. Although valued in its fixed setting, where it can be observed at a distance, Black art and storytelling is too often incarcerated. There is power and transformation in the stories of Black creatives and innovators. We need these voices to inform the future of our society.

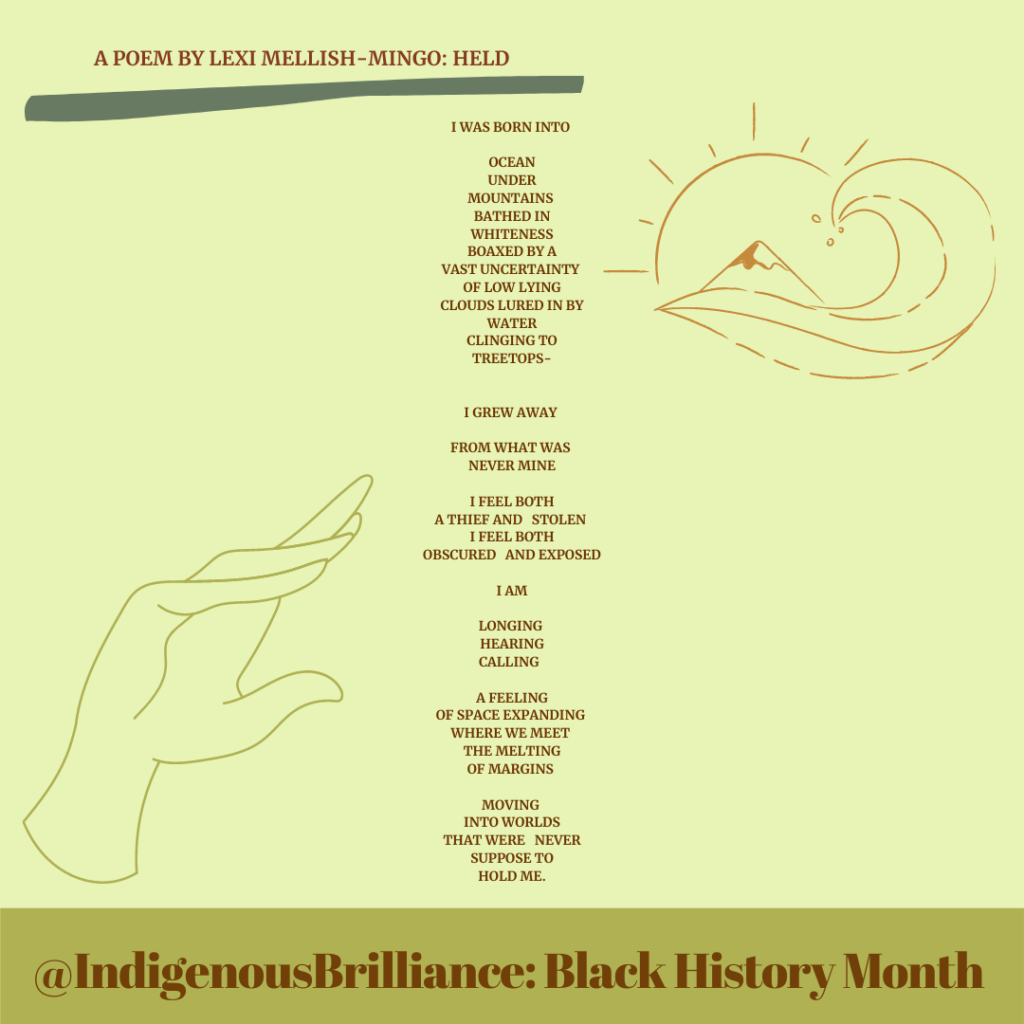

Held by Lexi Mellish-Mingo

i was born into

ocean

under

mountains

bathed in

whiteness

hoaxed by a

vast uncertainty

of low lying

clouds lured in by

water

clinging to

treetops-

i grew away

from what was

never mine

i feel both

a thief and stolen

i feel both

obscured and exposed

i am

longing

hearing

calling

a feeling

of space expanding

where we meet

the melting

of margins

moving

into worlds

that were never

suppose to

hold me.

Karmella Cen Benedito De Barros: Alright, so to begin could you please introduce yourself, tell us a little bit about the film project that we worked on?

Lexi Mellish-Mingo: Hello my name is Lexi, and you and I collaborated on a film project called Where We Meet, which came out of having mutual experiences and creative visions. It seemed that at the time we were just developing our collaborative relationship. We tried to collaborate on funny little business projects before, but we started to think about film around January last year or even earlier than that. And I remember meeting up at a cafe and both having these ideas about how we could make a film on how to depict our experiences navigating Blackness, or our experiences of Blackness in the City of Vancouver or North Vancouver where we grew up. The film that we made was a product of coming together and that’s why it’s called Where We Meet, I guess, because we came together and we met so many people along the journey. Originally it was just talking about the shared experiences that you and I both had, and also the divergent experience that came up during the process. It was like “how can we depict this shared experience in a place that has such an erased history of Blackness and erased experiences?” Like, how can we talk about the diverse experiences and the experiences that are similar?

KB: What’s one of the biggest things that you learned from making the film?

LM: I learned a lot from you. I learned that I can’t assume one experience. That was a huge thing for me to get over because I felt like it’s true, we’re navigating from our own experience, but everybody is so different. There are intersections and there are divergences, and that was a huge thing for me. And also something that was very important to me was realizing that everybody has their own thing to offer, their own unique stories. Making space for that was something that became more and more important throughout. It was like “oh, wow..” to listen and receive this knowledge from people is a true honour, and I didn’t realize I valued that so highly: learning from others, especially people that are like aunties and mentors to us now.

KB: I think it’s important to also have spaces that are dedicated to just Black people and are celebrating Black people telling Black stories, and just because our film is centred in that doesn’t mean that we as people aren’t doing the work to show up to fight for Indigenous sovereignty and to fight for Land Back and to learn protocols and how to respect the land and the people. Thank you for sharing.

A lot of our film showcases a body in relationship to the land, and a community that was formerly known as Hogan’s Alley, and I’m wondering if you can share a little bit about Hogan’s Alley and why we chose to film there, and what was the story that we were trying to tell through the film?

LM: Hogan’s Alley is what we refer to when we talk about the community that was housed in and which became a cultural hub for the Black population here in Vancouver. Most people might already know about it, but I think our relationship to that space has only been growing in the last, like, two years. My knowledge goes back maybe three years ago, and they’ve been doing work since 2002 and earlier. But I don’t know how to talk about it and reclaim the space. I think that making a portion of the film there was somewhat of a spiritual experience, because it was the land that stories lived on, it was the land that people thrived on, but it was also a reclamation and a space where we could create and we could build.

I think that when we were on the viaduct, on the side where Norah Hendrix Place is, and at the Militant Mothers overpass, there was something powerful there. I think that by going there and performing in those spaces – there’s this word, a “palimpsest” and it’s like writing overtop of history – it’s like building over top and creating layers. I think what we were trying to do was show our appreciation, respect, and acknowledgement to a history that has been intentionally erased.

But going back to the other question, we still are on stolen land, so how does this relationship reflect all of that too? I’m still trying to figure it out. It felt like a very important and sacred experience to be on that land, and in those spaces that once held community for Black folks, but then at the same time, beyond that history, what was that space? Because I know Strathcona, it used to be some sort of waterway, and I want to know more. I also connect with water and I also appreciate the idea that the land still speaks underneath concrete.

KB: I think that’s a good point. There’s always more to learn and always layers to peel back, and we might come into these parts of history that we didn’t know about, but then we can dig even deeper and learn even more. It all builds on top of itself to get to where we are today and we’re still making history today in the work that we’re doing and the ways that we’re living, but I agree that when we were filming in those areas, it did feel very powerful and I think a lot of that has to do with the fact that we just knew how important that space was to people at one point in time, people who were like us. I think it was really beautiful to imagine a community and a group of Black people, like a physical space where you could look around and see a bunch of people that looked like you and a bunch of businesses where the owners looked like you, and to feel like there was somewhere in the city where you really belonged, because as displaced people without Hogan’s Alley now, there’s not really a place like that anymore. It’s a very fragmented experience of community, which I think we highlight in the film and something that we talk about wanting to reclaim. And the process of filming was us trying to reclaim some piece of that in a way.

LM: Mhmm, and I think that the title Where We Meet when I think of that, and I think of all the work we did at the end. I kind of saw our film from a bird’s eye view, like this underground subway station, and then on top of a layer of the buses, and then the bike routes and then the trails and the pathways, and like where we meet is all these intersections that are transposed on top of each other. That’s a visual that keeps coming to me.

KB: Yeah, like it’s not just one place, or one community, or one neighbourhood anymore, but there are these small places that we do come together and that do intersect, and that’s something to cherish and to build on moving forward. I feel like the film is ultimately a hopeful piece because we’re really talking about what we want moving forward.

What do you imagine community for Black people could look like and feel like in this city?

LM: So far, being that there isn’t a cultural hub, and being that there’s no clear sight of a cultural centre, despite the city promising it and approving it, I think the biggest thing for me for the future would be that we continue as Black folks in the city to collaborate with other Black folks and Indigenous folks, and bring people together through the process of sharing ideas, and not being this singular monolith. Like, we help each other succeed and maybe that’s creatively, maybe that’s through activism or a movement. I just think that as we navigate our own experiences, I hope that the future holds more collaborations between different people, and it doesn’t have to be just Black people. It doesn’t have to be exclusive. Just be intentional about who you collaborate with to create a future that brings people together.

KB: I think that’s a good point that it doesn’t have to be exclusively building Black futures or Black communities in the city, but rather building on relationships that centre and prioritize holding a safe space for Blackness and for Indigeneity, and the ways that those two identities intersect and overlap, and the ways that they’re different. It’s important to have space within our relationships to hold these identities as sacred, because we are historically the most oppressed groups of people, so I think that we deserve futures where we can be held in a good way.

LM: Totally. And that intentional work. It’s so true, it’s not about exclusivity, but rather remembering that we can prioritize us, and in doing so we create that future. We can’t see an Afro or Indigenous futures without our voices, without our stories, without our projects and our ideas. That’s how we’re going to save the world.

KB: We were talking the other day about Black History Month and about how not a lot is going on in the city of Vancouver doing anything for Black History Month, and I’m wondering, what does Black history month mean to you and how do you want to see people acknowledging us this month and all the time moving forward?

LM: I can’t speak for every Black folk but I often hear “Black History Month is every month,” and yes, this is true when you’re in a Black body, it is. We’re always learning our histories. But I think that I really like what you all are doing, giving book recommendations, but I guess not everybody reads so I think that it’s pretty upsetting that Vancouver has done nothing, especially in a turbulent year like this, to show that the city is trying to be progressive. I guess what I would like to see is just a bit more people showing up to share power and privilege. Like more people offering opportunities rather than money. That would be really cool to see people coming together in that kind of way. Redistribution of wealth would be good. I really love what Shanique is doing. They’re going to share knowledge and people are going to pay them. That will be cool. I hope to see more resources shared.

KB: Like empowering people to share their stories and share their voices because we all know a lot, and we just need the opportunities to be able to share what we know.

Thanks for tuning in for Indigenous Brilliance and Room Magazine’s celebration of Black History Month. Keep an eye out on our @indigenousbrilliance instagram and Facebook page for more content and the event link for a screening of Where We Meet on February 28th! Check out our past post What does Afro-Indigenous/Black-Indigenous Mean?