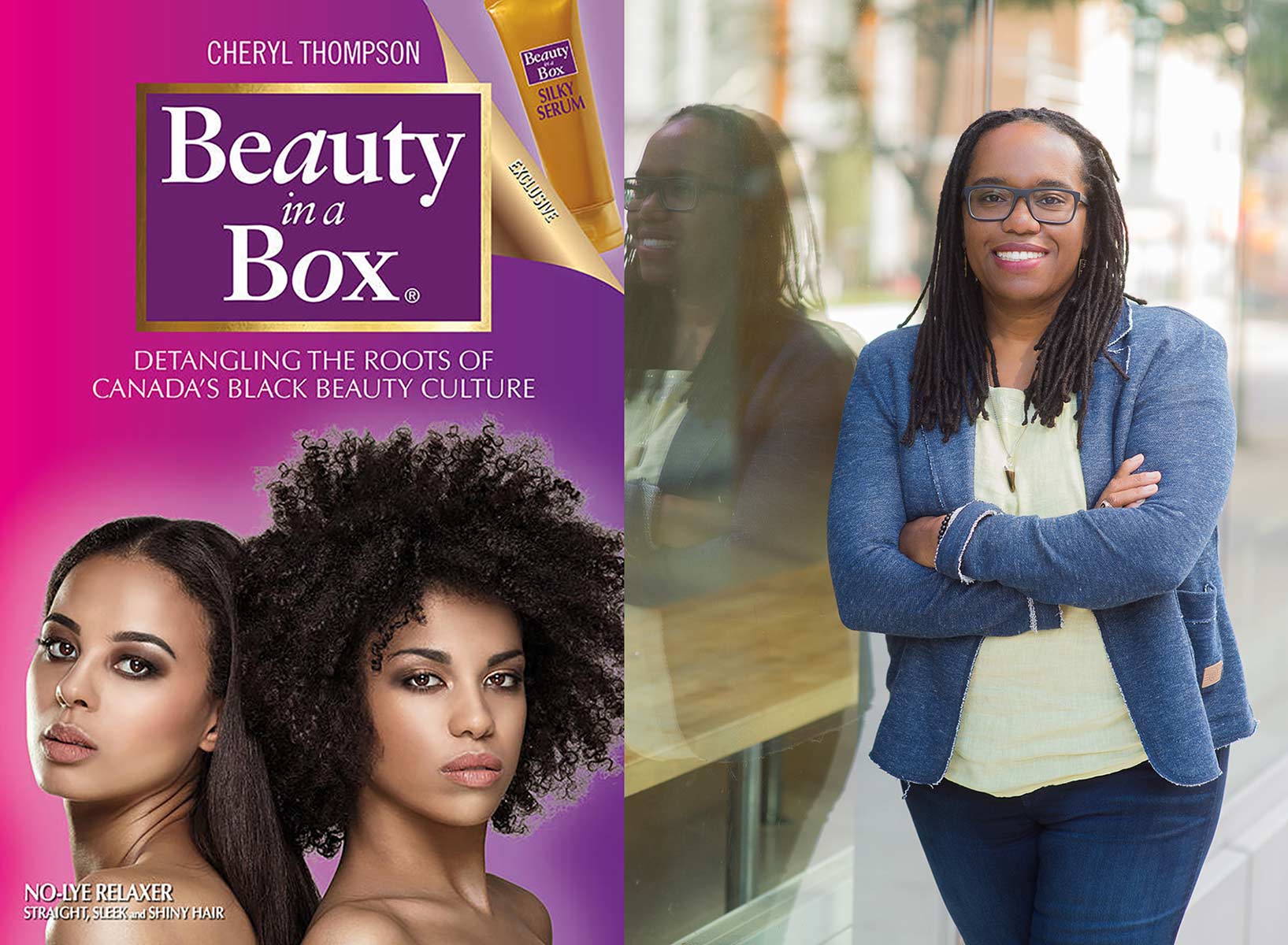

Dr. Cheryl Thompson is a writer, author, and academic. She is an Assistant Professor at Ryerson University in the School of Creative Industries. Her book, Beauty in a Box: Detangling the Roots of Canada’s Black Beauty Culture, was published with Wilfrid Laurier Press in 2019. Her next book, Uncle: Race, Nostalgia, and the Politics of Loyalty, will be published in 2020 with Coach House Books.

Dr. Cheryl Thompson is a writer, author, and academic. She is an Assistant Professor at Ryerson University in the School of Creative Industries. Her book, Beauty in a Box: Detangling the Roots of Canada’s Black Beauty Culture, was published with Wilfrid Laurier Press in 2019. Her next book, Uncle: Race, Nostalgia, and the Politics of Loyalty, will be published in 2020 with Coach House Books.

There’s so much I wanted to include from the two-hour interview that Dr. Thompson generously did with me. An engaging and natural storyteller, her words stayed on my mind long after our interview. We spoke about Viola Desmond and her connection to black beauty culture that history doesn’t teach us, the movie Pitch Perfect and why representation is so important, and why we still see “the mammy” today. She spoke about the importance of believing in yourself and your work, her inspiration for the book and her hair journey, the dominant beauty culture, its past and present and how it affects the black beauty industry.

ROOM: I wish they would teach Beauty in a Box: Detangling the Roots of Canada’s Black Beauty Culture in schools. It’s essential reading for everyone because as Canadians, we don’t know our history.

CHERYL THOMPSON: I know. One of the things is that it’s a real book, not a collection of essays. This is like a narrative. From the beginning page, until the end. That’s why it took ten years. I’m very careful to take you through and not assume you know the things that I know. You don’t have to be an expert to read the book.

ROOM: For example, we know the story of Viola Desmond standing up for segregation at the Roseland Theatre in New Glasgow, Nova Scotia where she got arrested for refusing to leave the whites-only section according to Heritage Minutes from Historica Canada.

CT: Yes, pretty much.

ROOM: In your book, we learn she was a beautician who started her own beauty school. She didn’t have support in Canada so she had to go to the U.S. to study because in the ‘40s there was segregation here and “all of the facilities available to train beauticians in Halifax restricted black women from admission” (Backhouse, Color-Coded, 232.) We don’t know this.

CT: Part of the book is trying to tell people the things that people have had to do to survive. It’s about survival. Everybody thinks we’re on an equal playing field and all working hard, and some people are just left out of the game. They have to create their own game. They’re not even in it. For most of Canadian history, that has been the case for people who are not white, Anglo Saxon, Protestant and English speaking. That’s just the truth. We had to create our own game to survive.

ROOM: It’s on purpose too.

CT: We’re not taught to think of our history that way. It’s always as if these occasional things happened and we don’t know how they happened. It’s like, Sorry about that, eh. Actually no, that was a law that somebody decided, and now this is the effect of the law. We’re just not making the connection.

ROOM: We always act like it’s a one-off that didn’t happen again.

CT: Like a bad person made a mistake. Actually, they’re not a bad person. They’re a good person. They just made a mistake.

ROOM: Your book was published this year by Wilfrid Laurier University Press. You wanted to fill in the big gap in black beauty culture because there wasn’t a lot of information available in our Canadian historical records. Can you tell us about the ten years you worked on it and how this project came to be?

CT: It started as my Ph.D. dissertation when I was at McGill in 2009. Around 2007, I got dreads, and that’s when I started my own hair journey. I was always a writer and I wrote a series of articles and the reaction was people had never heard of this topic before. I thought I should do this with my Ph.D. I had a different project but because of the reaction, I had to do this. Then I went to McGill, and it became my Ph.D. dissertation. Every time I would go into archives and was doing work, no one had ever done this. People asked, what are you researching? They couldn’t even help me and didn’t even really know what they would show me. So as much as that was a negative experience, it kept reaffirming that I needed to keep doing this book because no one has done this and it has the potential to reach people. So, then I finished my dissertation and knew right away that this was a book. Some people will always tell you the worst-case scenario. Everyone would tell me, “Oh you gotta send it to a lot of publishers. You’re going to get a lot of rejections from publishers.” Anyway, so every publisher I sent it to was like “Yes! We want to publish this!” I spoke to several publishers, and I narrowed the list down. University of Toronto Press (U of T) was the first publisher, but my editor left and went to Wilfrid Laurier, and I didn’t want to leave it where it was going to get lost with people that I didn’t know. So, I took the book with her to Wilfrid Laurier because I really liked her as an editor. She really understood.

ROOM: I thought that you were a historian from reading your book.

CT: That took years to kind of hone. I call that book the fun fact book. [Both laugh]

ROOM: I knew I couldn’t gloss over this information.

CT: There’s just a lot in there. You’re also connecting so you might read something and think, Oh I remember that or I didn’t know that yet. Even though I’ve been dealing with it for almost a decade, I remember the last copy edit, I was reading like it wasn’t me. Oh wow that’s interesting! I wrote that! I was still excited about the words and what I was saying. Because at that point, I don’t remember the process of writing. Ten years is a very long time to stick with a project. Most people would have just given up. Oh, it’s taking too long. I don’t remember the initial stages of writing it. It’s gone.

ROOM: I love what you said, people were saying oh it’s going to get rejected, and actually (gets book proposal accepted).

CT: I tell this to my students now, you have to believe in your work. Even when I was doing my Ph.D. at McGill when I would tell people that the book is a history that would span from the nineteenth century to today, their first reaction was oh that’s a very big time span, are you going to be able to,… They would project all this fear and worry on me, I don’t think you’re going to be able to do that. You have to pick a time. I was just like, No, no, no, I got this. I’ll figure it out.

What I am most proud of is in that book is that I’m able to go into history and talk about history, and its context and bring it forward into the present. What makes it unique is that it makes everyone see the connective tissue between the past and present. People don’t write like that. They’re either in the present or the past but they never really connect it together. I made an effort to bring the two together. That’s why it took so long.

ROOM: I was shocked about the archives and how no help was available. In some places in the U.S. there was help with the research, but in Canada you were left on your own and often records were untouched.

CT: They literally give you a box, and say good luck. Let me know if you need any help. So, that’s going to lead to another project, to do the work of cataloging Canada’s black archive because that work needs to be done. There are so many archives that have black holdings that they don’t even know they have them. If you’re a researcher, you have no resource guide to say, this archive has this. But then also make a connection that there might be things in that archive that connects to an archive in a different city. The people being trained as archivists are not being trained on how to read black collections. So, it could be very frustrating when you’re trying to do a project on black subjects. You’re kind of on your own.

ROOM: You wrote about black print media and how the community is so spread out across Canada, and that there were pockets and how you had to go find that information. Black porters were spreading the information.

CT: That’s the cool thing about the book when I talk about the networks. How they had all the networks to move things. People would bring things back even in my own lifetime. Even in Toronto in the ‘80s, there weren’t a lot of black beauty product places. My mother would go to New York, and we would buy products. If someone was in New York and was coming up, she would ask them or sometimes they would plan bus trips up until a few years ago. No one’s looking at that critically as a network. They don’t understand that they’re creating a sub-economy because you can’t get them here. That’s an intricate network that’s happening, but nobody is framing it that way. Because the reality is that if you’re a black person living in 1950’s Canada, you weren’t walking into Walmart to get anything because there wasn’t a Walmart. You were completely left out of every retail space. In some places in the country, you couldn’t even use the dressing room. So, you had no space in the public sphere where you could go and see yourself represented. Yet, people say, “Viola Desmond had amazing outfits and hair.” How did they do this? Obviously, they had a sub-economy based on network and community.

ROOM: There’s this white beauty standard, which we see everywhere in the media. I’m noticing what you wrote about commercials appearing more diverse.

CT: And then… [laughs]

ROOM: The ads appear more diverse, but they’re not.

CT: Sometimes, you just need someone to point it out to you because you’re not really paying attention. It’s the qualitative nature of the representation that people don’t pay attention to. They’ll say, hey look there’s an Asian guy, there’s a black woman. That yeah, there’s an Asian guy, but he’s got no family, or there’s an Indian guy, but he’s got no family, he’s got no friends. He’s just a static person. He doesn’t have any culture. He’s a brown guy. Yes, there’s a black woman, but again it’s like she’s really loud, she’s angry, she’s screaming and yelling, she’s doing something crazy, and then there’s Becky looking like the most normal person with friends, family, right?! It’s how everybody is pitted against each other. You know that movie, Pitch Perfect? I love the series, I really do, but when you watch that movie, the white characters are so normal—every white, straight character. The queer character is really “off.” The Asian girl can’t even talk. She’s weird. The black girl, she’ll be randomly angry for no good reason, like outbursts. Whereas all the other white characters are like a diversity of that group. They’re able to process information, emote in a normal way, and engage with each other and problem solve and do all those things. On a cognitive level, every time you’re watching those movies of course you’re going to think “well, white people are normal. Everyone else is abnormal.”

ROOM: They’re not often the main characters just extras or secondary characters.

CT: A best friend. They want to bring diversity, so they have the black best friend. She has no family; her whole purpose in life is to support the white friend in whatever they’re doing. You’ll even have scenes in the movie where they cut to the black friend on the phone and she’s coaching the white friend about her life. If we really want to break it down, that is “the mammy” archetype. That is the continuation of the Southern maid. It just looks different. That is the continuation of us just continuing to support you in whatever it is that you’re about to do, and we have no personal life, family, or feelings. We’re only there to help you with your feelings, and I think these representations are dangerous because they trigger into real life. Then sometimes the racial dynamic in your real life is why does Becky always think I’m here to help her? We’re colleagues, we’re doing the same job! It’s like we don’t know where that’s coming from. Well, it’s coming from every single thing that you’ve ever seen that tells you that we’re there to help you. And you’re not, on a cognitive level, aware that this is where it’s coming from right? Because these things are working on a subconscious level.

ROOM: You’re absolutely right.

CT: I’ve seen it happen. It happened in my own personal life, but how do you talk to this person about that because they’re going to deny it, and they’re going to say, well that’s not true. It’s a hard conversation to have.

ROOM: They don’t like to have those hard conversations.

CT: No, because they’re not paying attention. In their head, they’re thinking “I value your opinion.” I trust what you have to say. How can you break things down on that level when they don’t know anything about me? I had a friendship with a white woman for almost ten years, and at the end of it, she sent me an email like it was a contract. She said I think we need to part ways. I don’t really see where you’re growing, and all this nonsense and I thought to myself, Oh my gosh, I think this person in their head, thought I was only there to help them because they got a job. I was only there to help them get this job and then once they got the job, well where could the friendship go? It’s like I served my purpose in her life. This is how I know that these images do have real-world impact in your day to day.

ROOM: As you said in the book conclusion on page 258 “…when all women acknowledge that the same companies that market to American women are companies that market to Canadian women and to the rest of the world, we can begin to have a conversation about “real beauty.” We have to acknowledge where this standard of beauty is coming from.

CT: That’s why in the book where suddenly it seems like I’m on a detour, talking about white womanhood and Chatelaine magazine and all the ways that the mainstream ads and the mainstream beauty product companies came to Canada in the ‘40s, I’m doing that on purpose so that people can understand how processes of exclusion happen on a structural level because all those companies, all those brands came to Canada, but they were targeting white middle-class women exclusively. Nobody else existed for those people. If we jump forward and think if that’s the root of how they came to Canada, that’s probably still the root today and that explains why you could be in a class with black and white women and the black woman will feel disconnected whereas the white woman in that class will feel validated. One of the critiques that you hear is why didn’t you say anything if you felt disconnected? It’s really hard to point out to people who don’t have any insight that the way they’re living is excluding them because they’re not looking at it that way. They think, I’m choosing, you’re choosing, everybody’s just choosing. While the book is about black beauty culture, I wanted to show the distinction to not just focus on black beauty culture. You can’t understand it without relation to the dominant beauty culture. Especially when I start talking about all the mergers and acquisitions.

ROOM: There are no manufacturers of black cosmetics or hair care in Canada now.

CT: Not on a major scale. On a Mom and Pop scale, there’s always going to be the sole entrepreneur whose going to be making actual hair products. We’re talking about the mainstream black beauty culture like hair weaves and wigs, and chemical relaxers. There’s no company in Canada doing that. Everything is imported.

ROOM: And about Korean hair merchants since the ‘90s and the role they play.

CT: They’ve just taken over black beauty culture and now, it is about alterations. Hair weaves, wigs, lace front wigs, chemical relaxers, all the products that come with that. The natural hair market is still majority black-owned. So, if we take the ‘60s, Ebony magazine and the afro, right, a lot of people are really shocked to know that a lot of black hairstylists at the time, did not like the afro because they were losing business. Ebony documented this tension in its January 1969 issue. Since then, here’s the dilemma in the black beauty culture industry, if more black people become natural, the truth is that profits will go down. Once your hair goes natural, you don’t have to do much with it. You don’t need a lot of products or need to go to the hair salon often, so it is not in the interest of black beauty culture for black people to become natural. Even though since around the early 2000’s they’ve created a lot of natural hairlines. The reality is if you wear your hair natural, you’re not buying any of those products. So, there is a conflict in the black beauty culture industry because they do need people to alter their hair. That is where the money is. You have a product dependent population when it comes to wearing lace front weaves, chemical relaxers, weaves, you’re just going to need to constantly buy a lot of products and spend a lot of money. Some women might be spending upwards of three to five hundred dollars a month, on hair weaves. Take that over a year, that is a lot of money for one person. And you extrapolate that to like ten million there’s a lot of money to be made in this.

ROOM: There’s also the toxic effects of using these products, and spending all this money to look at what’s considered professional, the white ideal of what that is.

CT: I’ve never worn a weave so I don’t really know the mentality of a person that would wear a weave, but I have friends who wear wigs. Some of them wear wigs because of the workplace because there’s a certain aesthetic, not just on black women, even white women or ethnic white women, that get up at six in the morning just to flat iron their hair because they can’t go to work with their curls. So, it affects everyone but as it relates to the health effects the research didn’t come out until the late nineties, early 2000’s and people were using chemical relaxers as early as the ‘50s. Generations using these products before they started to do research. That’s not a causal effect, but a correlation between using these chemicals that caused uterine fibroids. Hair loss and alopecia are other things. I started using chemical relaxers in the ‘90s, when they were really at a groove, just before the global conglomerate takeover of the industry in the late ‘90s.

Every girl I knew permed their hair. I didn’t know anyone who didn’t. Even though it burned, and you would start to notice some hair loss, it’s amazing what can happen when your consciousness is not awoken because no one I knew equated that with our health. When that same demographic of women are getting uterine fibroids, who are having all these health problems and someone made a joke, saying, there are millions of black women who should come together and launch a class-action lawsuit against these companies because technically they lied to us. The warning never included that in the warning label. It’s just like smoking. Now they have to put that little label that says this may cause lung cancer, then why doesn’t the chemical relaxer box give us a similar warning about the health effects? That is an issue.

ROOM: Wasn’t the relaxer for softening rawhide?

CT: It was a chemical process that would soften rawhide, and at that time in the twentieth century, there were a lot of black entrepreneurs that were prototyping chemical products to straighten the hair. José Calva was the owner of Lustrasilk, and the first person to commercialize and distribute the chemical relaxer across the U.S. Then in 1954, Johnson products became the first company to create the home kit. Calva’s product had to be done by a licensed beautician. After 1954 different types of chemical relaxers were coming onto the market that was less harsh, more user-friendly, and by the time you get into the late ‘70s, there is a huge shift that happens with chemical relaxers. They create the no-lye relaxer.

This is how companies have really bamboozled us because they went on this whole campaign about how this is really safe, and it burns less. People went back to perming their hair. The only thing that doesn’t come with a negative is your own natural hair that comes out of your own head. That’s the only thing that’s not going to harm you. The reality of being a black woman is that your hair is always going to be the thing that makes you different from every group of people. Black men too. Being black, you are fundamentally different. Even if you’re biracial, your hair is still coarse, or it has a curl and from the minute you enter school, you’re different, and that’s something people don’t realize. How that can affect you especially when you’re twelve or thirteen, and you’re trying to figure out who you are. I permed my hair at fourteen. A lot of black girls I know permed their hair between the ages of ten and fifteen. That’s the age when you’re trying to figure things out, and you want to fit in, you want to find friends, and there’s a lot of personal identity issues that are wrapped up in a lot of these practices.

ROOM: You don’t want to be different.

CT: No, it’s hard! You go to school, nobody understands, and teachers make all these stupid comments. The teachers need an awakening in many different ways. Just because you’re teaching, doesn’t mean that your studying stops. You are not just a purveyor giving information, you need to keep learning, and being on top of who is in your class. A lot of these people are teaching and have no idea what’s going on with their students. At the university level to some extent we can be clueless because we don’t have such an intimate relationship with the students. But in high school and junior high it’s a pivotal stage in your development and they just don’t even understand what they’re going through. It gets read that the student is the problem and then they don’t drop out; they’re pushed out of school. Because every time they go to school, they have to explain themselves. Why you wearing that hairstyle? Why are you wearing that jacket? Everything has to be explained and people don’t understand what that feels like when you’re fourteen, and you have to explain why your hair is braided.

ROOM: You shouldn’t have to.

CT: You’re like, Why do I have to explain this to you? Then imagine you’re forty, you go to work, and somebody’s asking why your hair is braided. Here we go again. I’ve been dealing with this my entire life. Why do I have to keep answering this question? Then they say, oh why does she have an attitude? One of the number one racial dynamics in North America, even probably in Europe, is that white people feel as though black people have to answer to them. So, if you ask me a question, I have to answer you and tell you why? No person has to answer to another person.

ROOM: How did you keep this all organized after ten years of research?

CT: Files and files and files. I had to go through all these newspapers, and magazines, and then named each file, with a date and subject, and that processing took over a year. Because I had everything cataloged by month, date, subject, that’s when it became this story telling itself. Once you go into an archive, you’re not going to go back. That’s the unglamorous part of writing a book. Naming files for a year? Those were some lonely times [laughs].

ROOM: Let’s talk about your new book coming out in 2020. Uncle: Race, Nostalgia, and the Politics of Loyalty with Coach House Books.

CT: That book came out of a Banting Postdoctoral Fellowship studying Canada’s history of blackface. I met John Lorinc an editor at Coach House, and I started working on the ward which is a historical community in the center of Toronto. Coach House published the book The Ward about artifacts and the major archeological dig where they found tens of thousands of objects. One of the objects was Uncle Tom’s Cabin plate, and they wanted me to write about it. They had a series of talks inviting contributors to come and talk about the book, and when I talked about this plate and Uncle Tom’s Cabin the audience was amazed so John approached me and said you need to write a book. Then he read Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe in 1952. I explained that in my opinion, Uncle Tom’s Cabin is everywhere, that it never left us.

This book goes through the history of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the anti-slavery sentimental novel, and has turned into Uncle Tom, the minstrel show, then Uncle Tom, an advertising caricature that we have through Uncle Ben and other uncles, then a TV Tom, that we had through the Bill Cosby-esque kind of thing, then came a film Tom, where we had roles that Sidney Poitier was forced to play and then how Uncle Tom became a racial epitaph that people hurl in groups to basically police the boundaries of loyalty.

So, if you are deemed to be disloyal to black community, they will say that’s an Uncle Tom, and so now it is a negative. In 1852, Uncle Tom is a hero. How this one person who is not real, has endured all these centuries and is still used but in a completely different way than when the name and character were first created, is what interested me.

In 2018, there was a film that came out called Uncle Drew. Uncle Drew is an NBA player who creates this alter ego character where he’s this aged man who goes onto the basketball court, and because he’s really an NBA player he turns it on and starts dunking and playing. Who is Uncle Drew? Uncle Drew is this old African-American man who talks about the past as the good old days. Why is the dominant culture so invested in old black men speaking heartfelt about the past, that the past was somehow better? Why did they always want to keep us in the past? If you start to pay attention, you’ll notice anytime there is an old African-American man in a film he’s always saying, oh the good old days.

You see that mythology playing out right now in the US where you have a fraction that keeps saying how great the past was, and we need to take America back, and we need to go back. Whereas the reality is not just for black people but for all racialized others, the only thing that matters is the present and the future. We don’t want to go back to the past. That’s not a good time for us, whereas the dominant culture is very invested in returning to what was a simpler time and a simpler time just means that everyone else was in their place and everything was about them.

ROOM: Yes, exactly that.

My teammate/assistant editor, Mridula wanted to ask you these next set of questions. About dialogue across identities when it comes to hair. Of newly arrived black immigrants and refugees. She said she knows they experience racism upfront but wondered how hair is talked about as a vehicle within communities.

CT: If we’re talking about across various black communities, there’s a universal sameness. It doesn’t matter if you’re in Africa you can be in Ghana, Nigeria, South Africa, South America, Canada, and the UK and France. We all experience very similar things with our hair in terms of, it’s the major question of, what am I going to do with my hair?

Even in African countries there is still this idea of being professional and having straight hair if you work in the government or for a company. Even in Africa you think it’s the motherland that is rocking their afro, if anything a lot of African women are wearing a weave or a wig more so than even in the West.

In Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s book Americanah, she does a great job describing what it’s like when she went into a hair salon in Philadelphia to get her hair relaxed for the first time. So, related to my own experience. She talks about moving to Philadelphia when she’s from Nigeria, and she goes into a hair salon and gets her hair done for the first time, and she explains that feeling of loss. It’s like an immediate feeling of loss. At the same time feeling like a completely new person when you step out with long flowing straight hair, I felt that across culturally, it doesn’t really matter. Just on a psychological level, you feel different, and that cuts across every culture. It doesn’t matter where you’re from.

ROOM: What do you think hair means to or for women who cover their heads? So often the absence of something makes for all sorts of assumptions. How we stereotype women who cover their heads for religious or other reasons.

CT: Like women who wear headscarves or hijabs? It’s still the same. There’s a lot of the reasons why women wear the headscarf in school. Yes, there’s the religious aspect according to the young Muslim girls that I’ve talked to but it’s also kind of to remove themselves from this beauty ideal. For me, on a personal level, your hair is your crown. Especially people of African descent, we were enslaved on these lands for how many centuries? For these other women, I understand where they’re coming from. Islam is still a religion that believes that men and women are fundamentally different. That men and women have a different role. In the West, we cannot wrap our heads around that we see it as oppressive. We really shouldn’t because if you look at Christianity, western religions have that fundamental belief too. We’re trying to act like we’re all equal but we really aren’t. There are very few women who are on that level especially in the Catholic church. Is there ever going to be a female Pope? Probably not. There are nuns and there are priests. So, we rank it as only Islam that promotes this gender divide in our religions when actually it’s in every religion. In Islam, it’s just very clear because it’s only women who wear the headscarf.

In some Orthodox religions men cover their heads too, with a cap. One of the things about living in the West is that we’re supposed to be free. We’re supposed to be individuals that can decide for ourselves. And yet every once in a while, there is something that seems to cut against that individuality because there’s a collectivism to wearing the hijab as well because it doesn’t matter your racial identity it’s a religious thing. That is a collective experience of covering. And it cuts across many different cultures too and countries. For whatever reason, in the West, we just don’t like collectivist displays of I don’t want to say religion or faith, but we just have an issue with it in as much as we claim to be a democracy. So, it’s just a paradox that for women who cover their hair the way they do, also have a kind of politics. To say, I resist this western standard of beauty is their politics.

At the same time, it’s contradictory because at the same time they will wear a full face of makeup. We all have our contradictions, and one of the things in the book that I’m trying to get at is can we just be comfortable in the contradiction. Why are we always trying to resolve things? Some things can’t be resolved. The reality is I didn’t write that book to say to black women to stop perming your hair and stop wearing a weave and a lace front wig. Because those things are always going to be here. I didn’t write the book to say that real black women wear dreads and afros. I’m here to say there are contradictions and what’s important is to just understand where the contradictions come from and if in your life that contradiction becomes too much, you can resolve it. You can do something about it. But if it’s not a contradiction for you just live your life. Just know the facts. That’s where I’m coming from, and I think the same thing with the hijab and the full face of makeup. It’s a contradiction that some can’t resolve. There are some Muslim girls that eventually stop wearing the head covering. Because they’re just like you know what, I just don’t want to wear it anymore. Then others decide to become more devout and they stop wearing makeup, and then they become more extreme. Like they might even change to wearing a hijab or burqa like they’re making people think that a man is choosing that for them but maybe in some instances some women are choosing to cover their hair and their full bodies. We have to be okay with these contradictions. Because it’s not human instinct to like contradiction. It’s not a good feeling.

ROOM: It’s uncomfortable for us.

CT: There’s certain things that we will never resolve and we’ll never be able to know why a certain group does that and why they don’t do this.

ROOM: Even in your book conclusion, didn’t you say it’s hard to conclude because it’s far from being done.

CT: How can you conclude something that’s still in the process of becoming? It is so complex, and so personal too. The thing about black beauty culture that I really want people to understand is that in as much as it’s personal, it’s a collective experience too. There’s that duality, and there’s that contradiction because the collective might want something but you as an individual want something else and then you’re always battling with, oh you know I’m going to a black church I got to wear a hat. I’ve got to have my hair a certain way, but I don’t like that so let me put on a wig, it’s easier that way. The, I won’t have to answer any questions. So, every time, every interaction you have with a group of people they are making all these last-minute life decisions. Do I wear a wig? Do I straighten my hair? Do I go natural? Do I wear an afro? Do I want to braid my hair? Because braiding now is like really politicized depending on where you are. There’s just a lot going on there. You’re never gonna be able to resolve those contradictions. So you know part of my book I really want to say to people stop trying.

Maybe it’s ok. Maybe the 21st century will actually become the first century where we all become comfortable in the uncomfortable. We’ve never been able to be uncomfortable with some things. Think about all the conversations that are happening in the world right now. I’ve been following the US political Democratic side. Most people are having conversations I couldn’t even imagine even in 2008 when Obama was running. It’s really talking about things that are kind of tough to talk about. This clearly says to me that we’re getting into an era where a lot of things are going to be talked about that will be really uncomfortable.

ROOM: I agree. Thank you for being so generous with your time.